It is unfortunate to note that the situation with respect to the experimental checks of general relativity theory is not much better than it was a few years after the theory was discovered - say in 1920. This is in striking contrast to the situation with respect to quantum theory, where we have literally thousands of experimental

checks. Relativity seems almost to be a purely mathematical formalism, bearing little relation to phenomena observed in the laboratory. It is a great challenge to the experimental physicist to try to improve this situation; to try to devise new experiments and refine old ones to give new checks on the theory. We have been accustomed to thinking that gravity can play no role in laboratory-scale experiments; that the gradients are too small, and that all gravitational effects are equivalent to a change of frame of reference. Recently I have been changing my views about this. The assumption of the experimentalist that he can isolate his apparatus from the rest of the universe is not necessarily so; and he must remember also that the “private” world which he carries around within himself is not necessarily identical with the “external” world he believes in. Particularly in the case of relativity theory, where one thinks one knows the results of certain experiments, it is all the more important to perform these crucial experiments, the null experiments. For example, the Eötvös experiment

Professor Wheeler has already discussed the three famous checks of general relativity; this is really very flimsy evidence on which to hang a theory. To go a little further back: the Eötvös experiment  ; the ratio is independent of the constitution of the matter. It does not prove exact equality of mass and weight,

; the ratio is independent of the constitution of the matter. It does not prove exact equality of mass and weight,  , which is quite a different thing! To considerable accuracy, it also shows that electromagnetic energy has the same mass-weight ratio as the “intrinsic” mass of nucleons, since in heavy nuclei the electromagnetic contribution is an appreciable fraction of the total binding energy. On the other hand, gravitational binding energy is generally negligible and one cannot infer its constancy from the Eötvös experiment.

, which is quite a different thing! To considerable accuracy, it also shows that electromagnetic energy has the same mass-weight ratio as the “intrinsic” mass of nucleons, since in heavy nuclei the electromagnetic contribution is an appreciable fraction of the total binding energy. On the other hand, gravitational binding energy is generally negligible and one cannot infer its constancy from the Eötvös experiment.

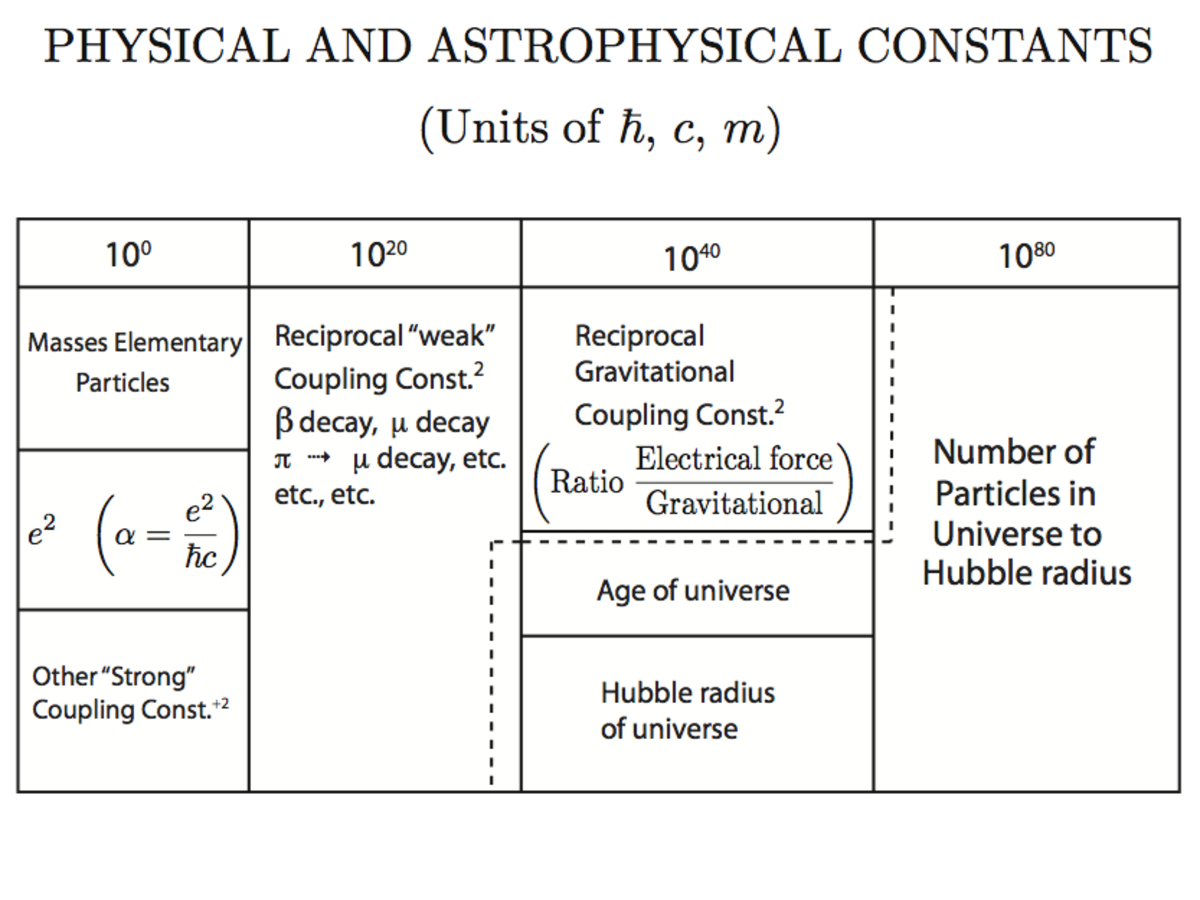

I would like now to refer to the table below, which may indicate where some of the troubles lie.

,

,

,

,

)

)Fig. 4.1: Physical and Astrophysical Constants (Units of

,

,

,

,

)

)

These are the famous  . At

. At

we have the gravitational coupling constant; everything so far has been an “atomic constant.” But also at

we have the gravitational coupling constant; everything so far has been an “atomic constant.” But also at

we have the constants associated with the universe as a whole; the age and the Hubble radius; while at

we have the constants associated with the universe as a whole; the age and the Hubble radius; while at

we have the number of particles out to the Hubble radius.

we have the number of particles out to the Hubble radius.

What is queer about these? The atomic numbers are queer because if we think nature is orderly and not capricious, then we would expect some day to have a theory from which these numbers would come out, but to expect a number of the order of

to turn up as the root of our equation is not reasonable. The other thing we notice is the pattern:

to turn up as the root of our equation is not reasonable. The other thing we notice is the pattern:

being

being

squared, and

squared, and

being

being

squared; and finally the strange equality of the “universal” constants - age of the universe, Hubble radius - to the gravitational coupling constant, which is “atomic” in nature.

squared; and finally the strange equality of the “universal” constants - age of the universe, Hubble radius - to the gravitational coupling constant, which is “atomic” in nature.

What explanations exist for these regularities? First, and what ninety percent of physicists probably believe, is that it is all accidental; approximations have been made anyway, irregularities smoothed out, and there is really nothing to explain; nature is capricious. Second, we have Eddington’s view,

The last of these appeals to me; but we see immediately that this explanation gets into trouble with relativity theory, because it would imply that the gravitational coupling constant varies with time.

Assuming that the gravitational binding energy of a body contributes anomalously to its weight (e.g., does not contribute or contributes too much), a large body would have a gravitational acceleration different from that of a small one. A first possible effect is the slight difference between the effective weight of an object when it is on the side of the earth toward the sun and when it is on the side away from the sun. This would arise from the slightly different acceleration toward the sun of a large object (the earth) and the small object. If we estimate his effect, it turns out to be of the order of one part in

on

on

, which I think there is no hope of detecting, since tidal effects are of the order of two parts in

, which I think there is no hope of detecting, since tidal effects are of the order of two parts in

. The mechanism of the distortion of the earth by tidal forces would have to be completely understood in order to get at such a small effect.

. The mechanism of the distortion of the earth by tidal forces would have to be completely understood in order to get at such a small effect.

Another way of getting at this same effect would be to look at the period and orbit radius of Jupiter, and compare with the earth, to see if there is any anomaly. Here the effect would be of the order of one part in

, which is on the verge of being measurable. Possibly by taking averages over a long period of time one can get at it; I haven’t talked with astronomers and am not sure.

, which is on the verge of being measurable. Possibly by taking averages over a long period of time one can get at it; I haven’t talked with astronomers and am not sure.

Another interesting question is this: are there effects associated with motion of the earth relative to the rest of the matter of the universe? All the classical “ether drift” experiments  , where

, where

is the ratio of earth velocity to light velocity. We know the velocity of the sun relative to the local galactic group; but we know nothing of the velocity of the galactic group relative to the rest of the universe, except that it is not likely to be much greater than 100 km/sec. Supposing it unlikely that the motion of the local group would be such as to just cancel the motion of the sun relative to it, we can say that the velocity of the sun relative to the rest of the universe is perhaps of the order of 100 km/sec. Then the annual variation in

is the ratio of earth velocity to light velocity. We know the velocity of the sun relative to the local galactic group; but we know nothing of the velocity of the galactic group relative to the rest of the universe, except that it is not likely to be much greater than 100 km/sec. Supposing it unlikely that the motion of the local group would be such as to just cancel the motion of the sun relative to it, we can say that the velocity of the sun relative to the rest of the universe is perhaps of the order of 100 km/sec. Then the annual variation in

, owing to the fact that the earth’s velocity at one time of the year adds to and at another time subtracts from the sun’s velocity, amounts to about one part in

, owing to the fact that the earth’s velocity at one time of the year adds to and at another time subtracts from the sun’s velocity, amounts to about one part in

. This could conceivably give rise to an annual variation in “g”

. This could conceivably give rise to an annual variation in “g”

There is, however, an indirect way of getting at this effect: any annual variation of the gravitational interaction would give rise to an annual variation of the earth’s radius, and hence of the earth’s rotation rate. Now such an annual change is in fact observed. The earth runs slightly slow in the spring. The effect is, within a factor two, roughly what you might expect from assuming 100 km/sec. and putting in the known compressibility of the earth. However, it is possible to explain it also purely on the basis of effects connected with the earth itself, such as variations of air currents with seasons. Also the irregular character of the variation indicates at least some contribution from such factors.

GOLD:

DICKE: It’s not too clear. Certainly part of it varies, but what the variation amounts to is not too obvious because its measurement depends on crystal clocks and they haven’t been too good until recently so we can’t go back far in time.

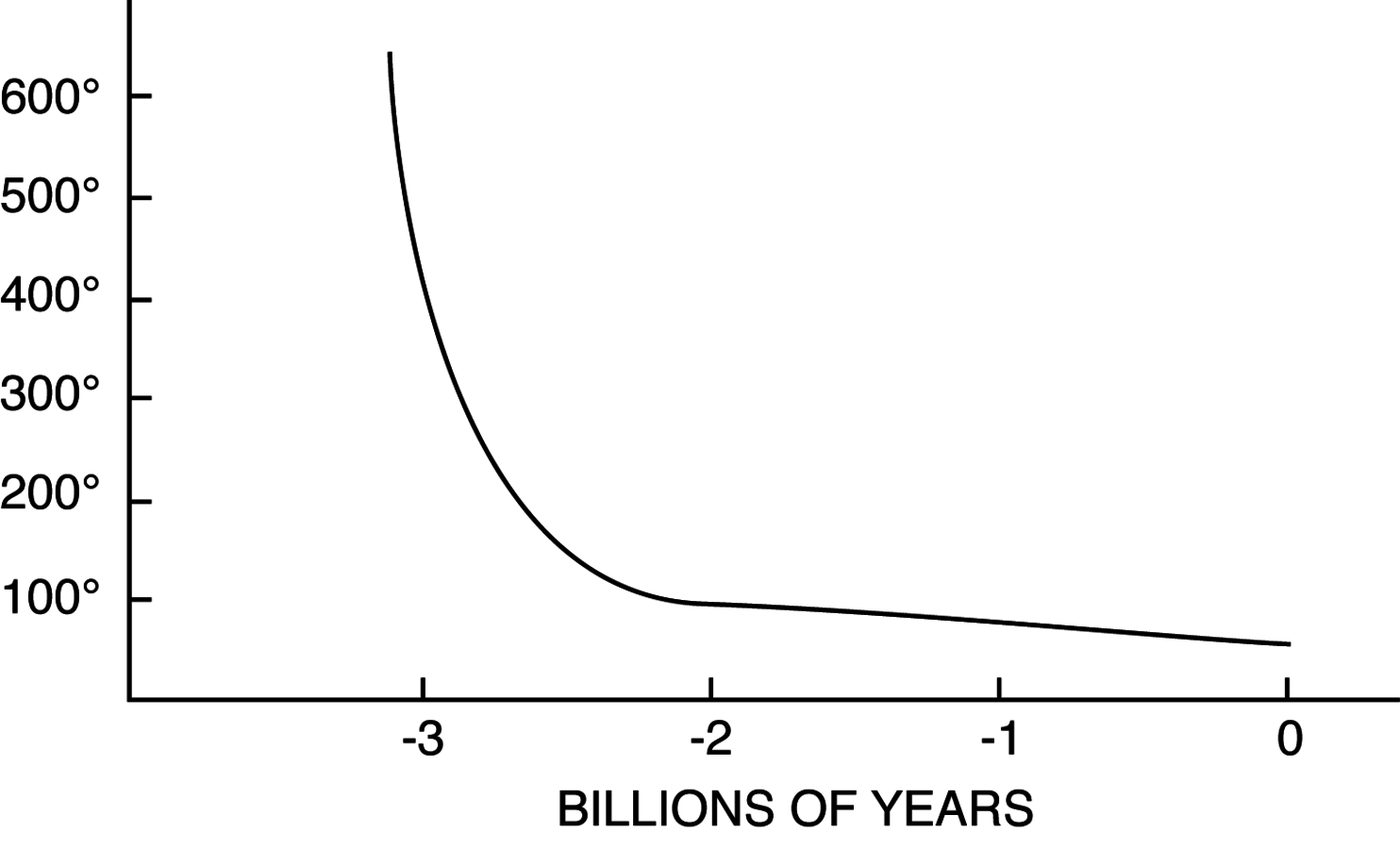

Now there is some other evidence on the question of a long period change in the gravitational interaction as we go back into the past. If gravity was stronger in the past, the sun would have been hotter, and we ask whether we can then account for the formation of rocks and creation of life. The accompanying figure (4.2) shows what we can say about the temperature of the earth.

This figure gives the temperature of the earth as a function of time as we go into the past, “0” on the scale representing the present. I have assumed that as the temperature rises, the amount of water vapor present in the atmosphere increases, and the sky becomes completely overcast. Then if we use the known albedo of clouds (.8), and the black body radiation in the infra-red, we get the curve shown for the temperature, assuming the age of the universe to be 6.5 billion years. The temperature rises slowly to about

C one billion years ago. Evidence for life as we know it exists back to about 1.0 billion years. Life could have been present back 1.7 billion years, when the temperature would have been about

C one billion years ago. Evidence for life as we know it exists back to about 1.0 billion years. Life could have been present back 1.7 billion years, when the temperature would have been about

C. According to biologists, algae from hot springs are known capable of living at such temperatures, so life could have existed then. There is evidence for a fairly sharp cut-off on the existence of sedimentary rocks at about 2.7 billion years, even though the solar system is about 4 billion years old. This agrees with our curve, since at the temperature corresponding to that age, about half the water would be in the atmosphere, and the pressure would be so high that its boiling point would be about

C. According to biologists, algae from hot springs are known capable of living at such temperatures, so life could have existed then. There is evidence for a fairly sharp cut-off on the existence of sedimentary rocks at about 2.7 billion years, even though the solar system is about 4 billion years old. This agrees with our curve, since at the temperature corresponding to that age, about half the water would be in the atmosphere, and the pressure would be so high that its boiling point would be about

C. There would still be enough liquid water to form sedimentary deposits. However, at slightly higher temperatures, the critical temperature of water would be exceeded, only vapor would exist, and sedimentary rocks would not have been formed.

C. There would still be enough liquid water to form sedimentary deposits. However, at slightly higher temperatures, the critical temperature of water would be exceeded, only vapor would exist, and sedimentary rocks would not have been formed.

I would say that the evidence does not rule out the possibility of the sun’s having been hotter in the past.

There is some additional indirect evidence arising from the problem of the formation of the moon. The moon has a density so low that there are only two possible explanations: first, different composition from the earth; second, a phase change in the earth that leads to a very dense core. The second is, however, hard

to believe, because if the core is assumed to be liquid iron, the total amount of iron in the earth is in agreement with what we believe to be the abundance of iron in the solar system as a whole. If we say the composition is different, we notice that it seems to be about the same as that of the earth’s mantle. This in turn suggests Darwin’s old explanation, that the moon flew out of the earth.

There is another bit of evidence on this: the moon is distorted in such a way that it has been called a “frozen tide”; it corresponds somewhat to the shape it would have had if it had frozen when at about a quarter of its present distance from the earth.

GOLD:

DICKE: This is true, but there is the possibility that the moon was somewhat plastic at the time of freezing so that the biggest distortions would have subsided somewhat to give you dimensions compatible with what is now seen.

GOLD:

DICKE: Yes; this is the other explanation for the moon’s shape, that big meteorites piled into it and made it lopsided.

Another piece of indirect evidence on this is connected with the problem of heat flow out of the earth. There is evidence for the earth’s core being in convective equilibrium; and heat flowing out of the earth’s core seems to be the only reasonable mechanism at present for a convective core. The question is how that heat gets out. It may be that there is radioactive material at the center which is the source of the heat flowing out; but potassium would be expected to be the biggest source of heat, and it is so active chemically that we expect to find it in the mantle only. If, however, gravity gets weaker with time, there would be a shift along

the melting point curve of the mantle which would lead to a slow lowering of the temperature of the core, and heat flowing at such a rate as to keep the mantle near the melting point. If we put in a reasonable melting point curve for the mantle, we find this contribution to the heat flowing out of the earth is of the order of

one-third of the total heat. So the evidence is not incompatible with the idea that gravity could be weaker with time, even though radioactive materials are of sufficient importance so that one would not attempt to account for the heat flow out of the earth solely on this basis.

There is some small bit of evidence that there may be something wrong with beta decay: the beta coupling constant may be varying with time. This comes from the evidence on Rubidium dating of rocks. The geologists on the basis of their dating of rocks assign a half life for Rb 87 decay of about

years. There

has been quite a series of laboratory measurements giving values of about

years. There

has been quite a series of laboratory measurements giving values of about

years; on the other hand one particular group has consistently got a value lower than five. So this is up in the air; but I think that before long we will have a definitive laboratory value for the half-life.

years; on the other hand one particular group has consistently got a value lower than five. So this is up in the air; but I think that before long we will have a definitive laboratory value for the half-life.

Finally, l may just mention last week’s discovery that parity is not conserved in beta decay. What the explanation for this is no one knows, but it could conceivably indicate some interaction with the universe as a whole.

DE WITT called for discussion.

BERGMANN:

DICKE: There are two experiments being started now. One is an improved measurement of “g” to detect possible annual variations. This is coming nicely, and I think we can improve earlier work by a factor of ten. This is done by using a very short

BARGMANN: About three years ago Clemence discussed the comparison between atomic and gravitational time.

DICKE: We have been working on an atomic clock, .

.

BONDI:

ANDERSON:

GOLD:

DICKE: One should also try seeing whether positronium falls in a gravitational field - but how can one do it?

GOLD:

DICKE: Is there some reason why it is better to do it with anti-protons rather than positrons?

GOLD:

WITTEN:  -meson in different frames of reference. Neither method has so far been carried to its highest attainable accuracy.

-meson in different frames of reference. Neither method has so far been carried to its highest attainable accuracy.

We are going to do the experiment using basically the techniques of Ives and Stilwell with improvements. We shall observe lines emitted or absorbed by hydrogen, helium, or lithium atoms or ions. The expected accuracy at velocities comparable to those used by Ives and Stilwell should be a factor of about 100 greater than theirs. By going to higher velocities the relative accuracy should be greater. We hope to measure the angular dependence of the effect; it has been measured so far only in one direction. lves and Stilwell1 have observed in their experiment a tendency towards disagreement with theory at high velocities and have suggested a possible source of experimental error that leads to this tendency. This point should be investigated. We shall eventually extend the measurements to

large enough to detect effects of the fourth order

large enough to detect effects of the fourth order

. We hope to develop techniques sufficiently well to do a precise measurement of the effect at highly relativistic velocities. Another goal is to make the time dilation measurement for ions moving in a magnetic field and being accelerated. The purpose here is to see if there is any shift in the spectral line of a kinematic origin due solely to the acceleration of the clock with respect to the observer.

. We hope to develop techniques sufficiently well to do a precise measurement of the effect at highly relativistic velocities. Another goal is to make the time dilation measurement for ions moving in a magnetic field and being accelerated. The purpose here is to see if there is any shift in the spectral line of a kinematic origin due solely to the acceleration of the clock with respect to the observer.