DE WITT

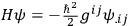

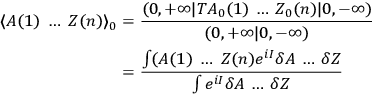

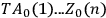

|

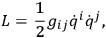

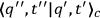

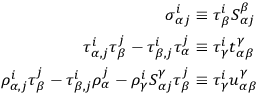

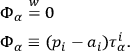

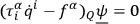

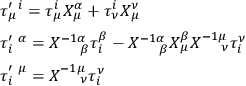

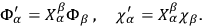

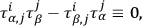

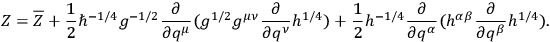

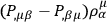

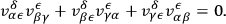

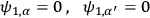

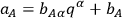

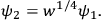

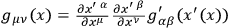

where the

may be functions of the

may be functions of the

’s and the indices

’s and the indices

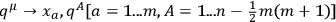

run from

run from

to

to

. The

fact that

. The

fact that

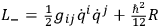

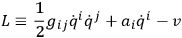

may be nondenumerably infinite is ignored. For an actual system the Lagrangian may possess other terms, but the essential difficulties are contained in the term considered. Inclusion of the other terms modifies the following discussion in no essential way.

may be nondenumerably infinite is ignored. For an actual system the Lagrangian may possess other terms, but the essential difficulties are contained in the term considered. Inclusion of the other terms modifies the following discussion in no essential way.

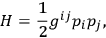

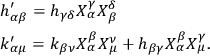

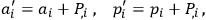

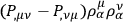

If (

) is a nonsingular matrix with inverse given by (

) is a nonsingular matrix with inverse given by (

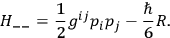

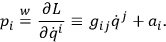

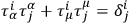

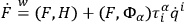

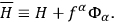

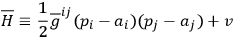

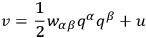

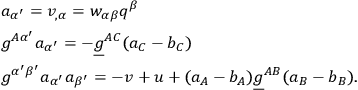

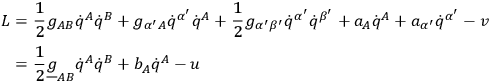

) then the system possesses a Hamiltonian function given by

) then the system possesses a Hamiltonian function given by

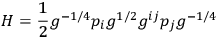

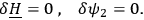

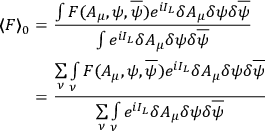

|

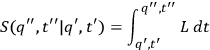

and the action

|

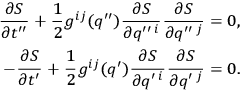

satisfies the Hamilton-Jacobi equations

|

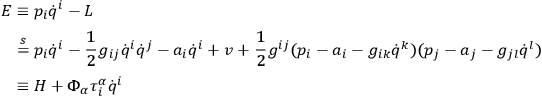

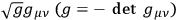

According to DE WITT, , which is already contained in the Lagrangian to be taken as the metric for the space of the

, which is already contained in the Lagrangian to be taken as the metric for the space of the

’s and provides the appropriate “measure” for a Feynman summation.

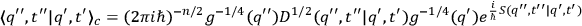

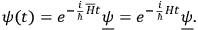

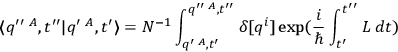

Following Pauli1 one may introduce a “classical kernel” of the form

’s and provides the appropriate “measure” for a Feynman summation.

Following Pauli1 one may introduce a “classical kernel” of the form

|

where

, and where the quantity

, and where the quantity

is a determinant originally introduced by Van Vleck in an attempt to extend the WKB method to systems in more than one dimension.2

is a determinant originally introduced by Van Vleck in an attempt to extend the WKB method to systems in more than one dimension.2

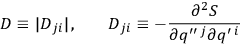

|

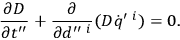

and satisfies an important conservation law:

|

which can be obtained by differentiating the first Hamilton-Jacobi equation with respect to

and

and

and multiplying by the inverse matrix

and multiplying by the inverse matrix

. From the quantum viewpoint this law expresses conservation of probability.

. From the quantum viewpoint this law expresses conservation of probability.

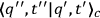

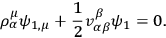

It is easy to see that

is an invariant under point transformations of the

is an invariant under point transformations of the

’s. With the aid of the Hamilton-Jacobi equations one may show that

it satisfies the differential equations

’s. With the aid of the Hamilton-Jacobi equations one may show that

it satisfies the differential equations

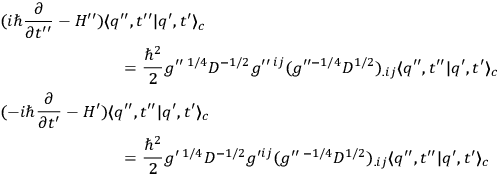

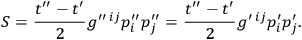

|

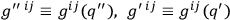

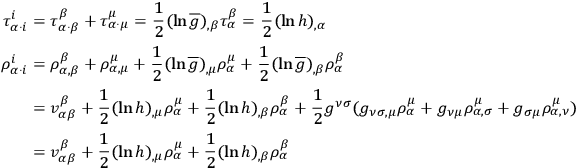

where for brevity we write

, etc.; where the dot followed by indices denotes covariant differentiation with respect to either the

, etc.; where the dot followed by indices denotes covariant differentiation with respect to either the

or

or

(as indicated by the context) and where the operator

(as indicated by the context) and where the operator

is defined by

is defined by

|

DE WITT  ’s is curved, the operator

’s is curved, the operator

could immediately

be regarded as the Hamiltonian operator for the quantized system. In order to discuss this phenomenon some further development is necessary:

could immediately

be regarded as the Hamiltonian operator for the quantized system. In order to discuss this phenomenon some further development is necessary:

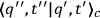

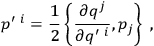

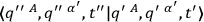

If one recalls that the classical action defines a canonical transformation by the equations

|

then one easily sees that the Van Vleck determinant is just the Jacobian involved in transforming from a specification of the classical path by means of the variables

,

,

, to a specification in terms

of initial variables

, to a specification in terms

of initial variables

,

,

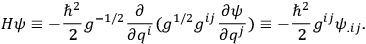

. From the Hamilton-Jacobi equations one sees furthermore that the action may be expressed in the form

. From the Hamilton-Jacobi equations one sees furthermore that the action may be expressed in the form

|

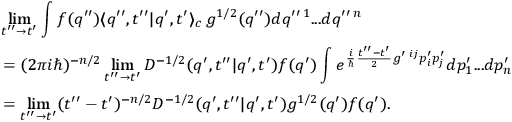

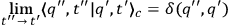

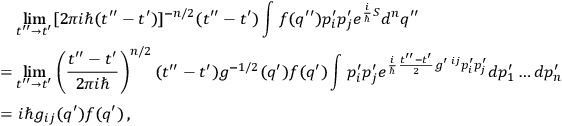

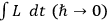

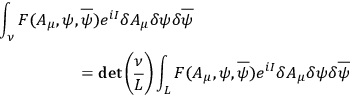

Therefore, noting that as

the

the

become infinite except when

become infinite except when

(for all

(for all

), one may write, for an arbitrary function

), one may write, for an arbitrary function

,

,

|

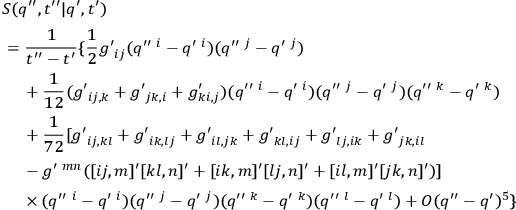

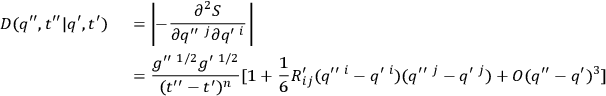

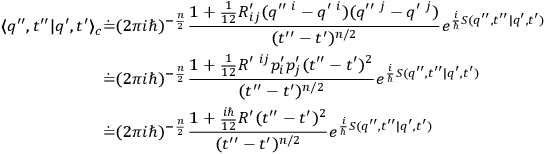

In order to evaluate this last expression one must evaluate the Van Vleck determinant. This is easily done by expanding the action about the point substituting it in the Hamilton-Jacobi equation. One finds, after a straightforward computation,

|

|

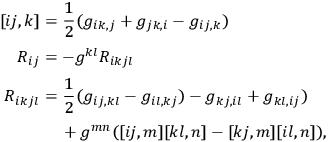

where

|

commas followed by indices denoting differentiation with respect to the

’s. Here a convention has been chosen so that the scalar

’s. Here a convention has been chosen so that the scalar

is positive for a space of positive curvature.

is positive for a space of positive curvature.

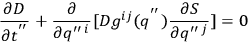

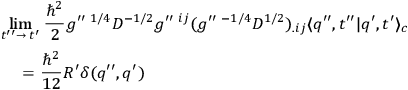

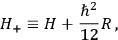

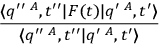

Using the final expression for the Van Vleck determinant one infers

|

and

|

where

is the invariant delta-function in

is the invariant delta-function in

-space. Referring to the differential equations satisfied by the classical kernel

-space. Referring to the differential equations satisfied by the classical kernel

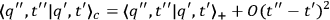

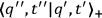

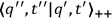

, one sees that it equals the true quantum transformation function

, one sees that it equals the true quantum transformation function

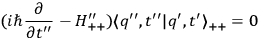

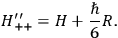

of a system possessing the Hamiltonian operator

of a system possessing the Hamiltonian operator

|

up to the first order in

. That is,

. That is,

|

where

|

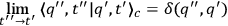

satisfying the boundary condition

|

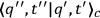

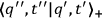

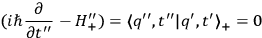

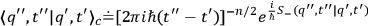

The “first order contact” between

and

and

is already

sufficient to determine the behavior of wave packets for the quantized system. If the system has a Hamiltonian operator

is already

sufficient to determine the behavior of wave packets for the quantized system. If the system has a Hamiltonian operator

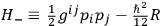

then its wave packets will more approximately along the classical paths of a classical system which has simply

then its wave packets will more approximately along the classical paths of a classical system which has simply

as Hamiltonian function. Conversely if the quantized system has Hamiltonian operator

as Hamiltonian function. Conversely if the quantized system has Hamiltonian operator

then the motions of its wave packets will be along the classical paths for a “classical” system which has the Hamiltonian function

then the motions of its wave packets will be along the classical paths for a “classical” system which has the Hamiltonian function

. Evidently there is an ambiguity here in the choice of Hamiltonian operator when the space is curved, and there is nothing in the classical theory to resolve it for us.

. Evidently there is an ambiguity here in the choice of Hamiltonian operator when the space is curved, and there is nothing in the classical theory to resolve it for us.

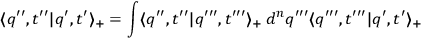

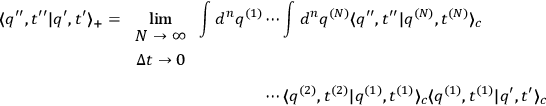

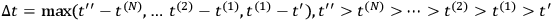

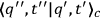

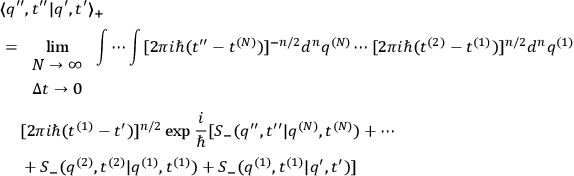

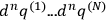

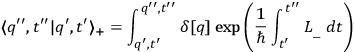

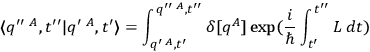

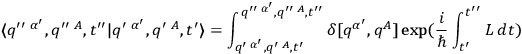

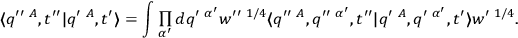

The Feynman formulation of quantum mechanics follows immediately from the order contact between

and

and

. Breaking the transformation function up into infinitely many pieces by means of the composition law

. Breaking the transformation function up into infinitely many pieces by means of the composition law

|

where

, one may write

, one may write

|

where

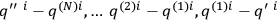

. It is evident, from the expression for

. It is evident, from the expression for

and the form of the expansion for the action

and the form of the expansion for the action

, that the (in the limit) infinitely multiple integral receives significant contributions from the integrand only when the differences

, that the (in the limit) infinitely multiple integral receives significant contributions from the integrand only when the differences

are of the order of

are of the order of

or smaller. Therefore, if the symbol

or smaller. Therefore, if the symbol

is used to denote equivalence as far as use in the infinitely multiple integral is concerned, one may write

is used to denote equivalence as far as use in the infinitely multiple integral is concerned, one may write

|

since

|

and therefore

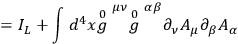

|

where

is the action function for the system with classical Hamiltonian function

is the action function for the system with classical Hamiltonian function

|

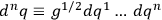

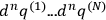

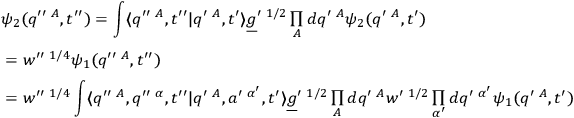

The Feynman formulation now becomes

|

and the dependence of the “sum-over-paths” on the metric

is seen to occur through the invariant volume elements

is seen to occur through the invariant volume elements

. This last expression is sometimes written in the symbolic form

. This last expression is sometimes written in the symbolic form

|

where the symbol

indicates that a “functional integration”

indicates that a “functional integration”  .

.

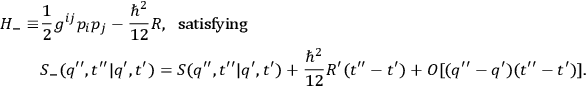

It will be noted that the last result is even more curious than the previous result obtained with the Pauli method using

. In order to obtain the transformation function for a quantized system having Hamiltonian operator

. In order to obtain the transformation function for a quantized system having Hamiltonian operator

one must use, in the Feynman summation, the action corresponding to a classical system

having Hamiltonian

one must use, in the Feynman summation, the action corresponding to a classical system

having Hamiltonian

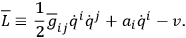

or Lagrangian

or Lagrangian

. When DE WITT

. When DE WITT  actually cancelled each other when one passed from the Pauli form on to the Feynman representation. J. L. Anderson later convinced him, however, of the reality of the phenomenon, by carrying out a computation patterned directly after Feynman's original paper.

actually cancelled each other when one passed from the Pauli form on to the Feynman representation. J. L. Anderson later convinced him, however, of the reality of the phenomenon, by carrying out a computation patterned directly after Feynman's original paper.

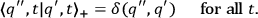

Instead of stating the result in a symmetric manner one may also state it in the following forms: If the true classical action

is used in the Feynman summation then one generates the transformation function

is used in the Feynman summation then one generates the transformation function

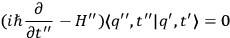

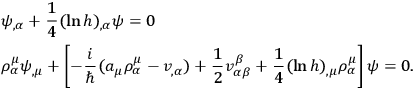

satisfying

satisfying

|

where

|

On the other hand, in order to generate the transformation function

satisfying

satisfying

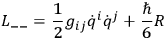

|

one must use in the Feynman summation the action for a “classical” system possessing the Lagrangian function

|

and Hamiltonian function

|

FEYNMAN remarked that quantization of a system like

is necessarily ambiguous when the space is curved.

is necessarily ambiguous when the space is curved.

DE WITT

In order to eliminate, right at the start, the degree of freedom transverse to the shell - which must have no reality in the end, anyway - one may suppose that the wave function has a simple node on each ellipsoid and none in between (i. e., transverse ground state). Since we know that confocal ellipsoids form a separable system for Schrödinger equation, we may immediately factor out the transverse part of the wave function and at the same time subtract a constant term proportional to

from the energy, where

from the energy, where

denotes the thickness of the shell at some point. The remaining part of the wave function then satisfies the Schrödinger equation with the simple operator

denotes the thickness of the shell at some point. The remaining part of the wave function then satisfies the Schrödinger equation with the simple operator

appropriate to an ellipsoid. This corresponds to a Feynman formulation using the classical Lagrangian

appropriate to an ellipsoid. This corresponds to a Feynman formulation using the classical Lagrangian

, for which the classical paths are attracted

to the region of greatest positive curvature, the attraction being described by a potential

, for which the classical paths are attracted

to the region of greatest positive curvature, the attraction being described by a potential

. In the present case the region of greatest positive curvature is the “nose” of the ellipsoid and here the shell is thinnest. The

three-dimensional wave function undergoes a “crowding” at this point. Since the transverse part of the wave function is constant, this crowding must be borne by the

“active” two-dimensional part. The tendency of the amplitude to increase in the nose region is describable in classical terms as an attraction. A wave packet would

actually display the effect of this attraction.

. In the present case the region of greatest positive curvature is the “nose” of the ellipsoid and here the shell is thinnest. The

three-dimensional wave function undergoes a “crowding” at this point. Since the transverse part of the wave function is constant, this crowding must be borne by the

“active” two-dimensional part. The tendency of the amplitude to increase in the nose region is describable in classical terms as an attraction. A wave packet would

actually display the effect of this attraction.

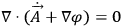

The Feynman formulation which starts with the classical Lagrangian

, on the other hand, corresponds to the use of a shell of uniform thickness:

, on the other hand, corresponds to the use of a shell of uniform thickness:

All points of the limiting ellipsoid are here weighted equally. DE WITT  .

.

(Editor's Note: - DE WITT's argument is not entirely rigorous. He, of course, avoided discussion of a spherical shell since the curvature is then constant and has only the effect of uniformly shifting all energy levels. However, there is a difficulty for ellipsoidal systems in that the separation constants are not themselves separable, and hence the transverse part of the wave function is not rigorously factorable for arbitrary behavior of the non-transverse part. It may, however, be approximately factorable when the shell is thin.

Attention should also be called to the fact that the behavior of wave packets is not described by the Lagrangian appearing in the Feynman formulation but by the

Lagrangian of the Pauli formulation, which is half-way between that of Feynman and the corresponding quantum form. Thus, when Feynman uses

, Pauli uses

, Pauli uses

to obtain the same quantum theory. Or when Feynman uses

to obtain the same quantum theory. Or when Feynman uses

, Pauli uses

, Pauli uses

. It is the Van Vleck determinant of the Pauli formulation which gives the key to the motion of wave packets, through its conservation law. Remembering that

. It is the Van Vleck determinant of the Pauli formulation which gives the key to the motion of wave packets, through its conservation law. Remembering that

, one may write that conservation law in the form

, one may write that conservation law in the form

|

If a wave packet is replaced by an ensemble of classical particles then

gives a measure of the density of these particles at any time and place.)

gives a measure of the density of these particles at any time and place.)

WHEELER

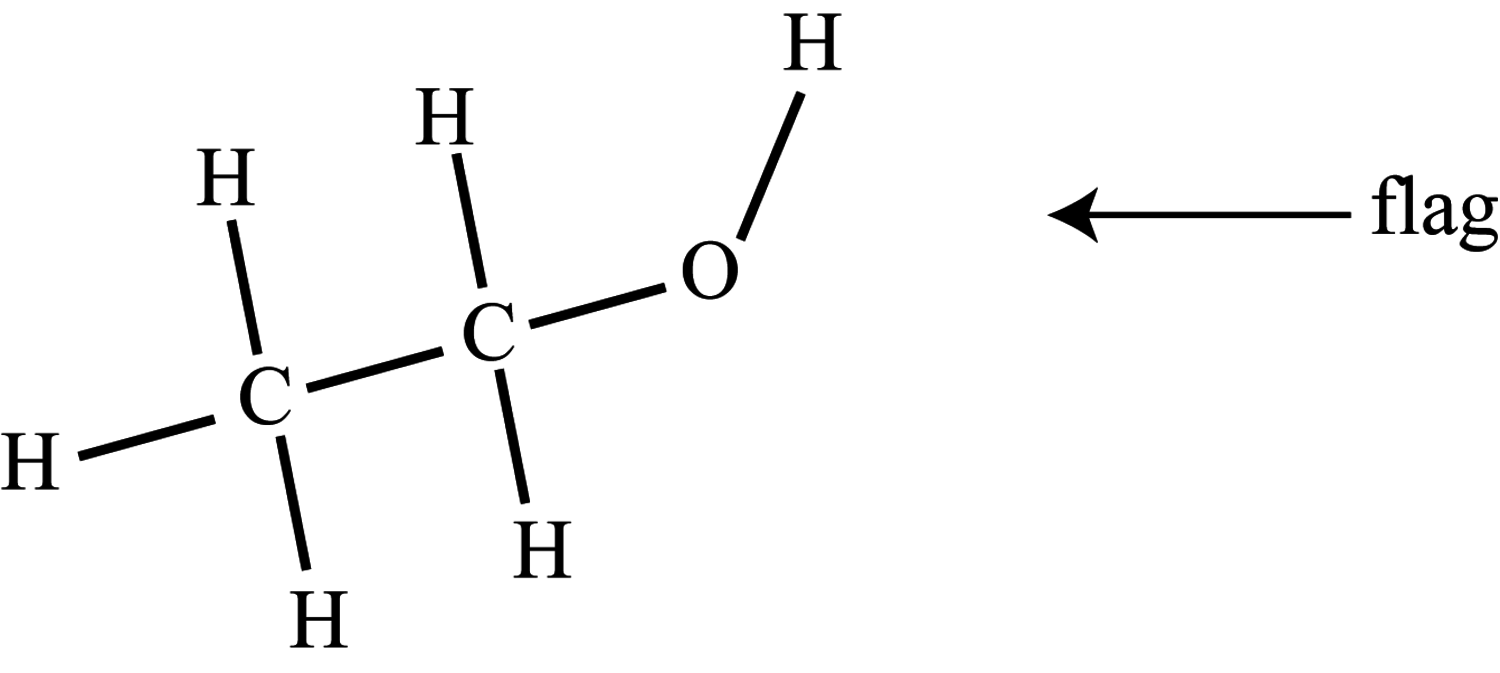

If some of the bonds are regarded as rigid (e.g., at room temperature) then the Lagrangian for such a molecule contains a metric corresponding to a space which is

not flat. However, WHEELER

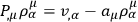

ANDERSON . This relation will not generally be satisfied if one chooses a metric for

. This relation will not generally be satisfied if one chooses a metric for

-space which is unrelated to the

-space which is unrelated to the

appearing in the Lagrangian.

appearing in the Lagrangian.

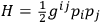

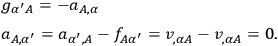

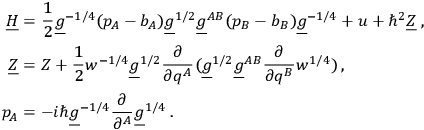

DE WITT then went on to discuss the second important and pressing problem which arises in the quantization of nonlinear systems, namely, the “factor ordering problem”: How should one order non-commuting operators to obtain appropriate quantum analogs of various classical equations?

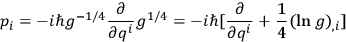

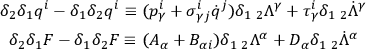

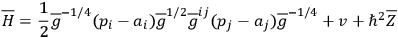

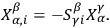

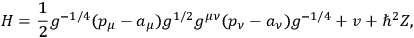

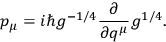

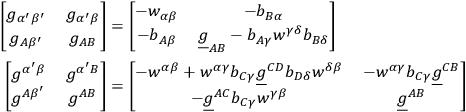

When the matrix (

) is non-singular the factor ordering

Hamiltonian operator is easily solved. The Hermitian requirement on the momenta

) is non-singular the factor ordering

Hamiltonian operator is easily solved. The Hermitian requirement on the momenta

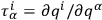

leads to the quantum representation requirement

leads to the quantum representation requirement

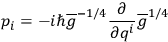

|

in arbitrary curvilinear coordinates. Hence, in order that

, one must write

, one must write

|

The Hermitian character of

is obvious from the symmetry of this expression.

is obvious from the symmetry of this expression.

For covariant theories, on the other hand,

is singular, constraints

is singular, constraints  is singular it is not obvious immediately what “measure” to use in a Feynman formulation.

is singular it is not obvious immediately what “measure” to use in a Feynman formulation.

(Editor's Note: - The following is taken from a set of mimeographed notes which DE WITT

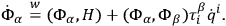

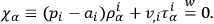

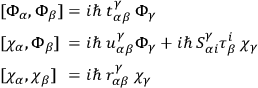

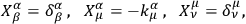

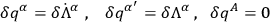

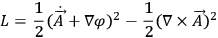

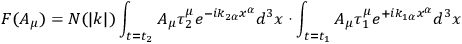

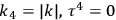

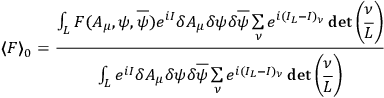

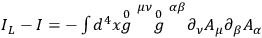

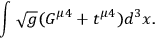

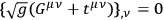

As a prototype of a covariant theory DE WITT

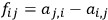

|

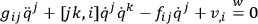

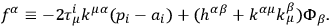

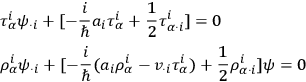

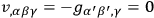

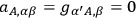

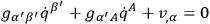

for which the equations of motion are

|

where

. These equations of motion are, of course, invariant under point transformations of the

. These equations of motion are, of course, invariant under point transformations of the

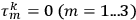

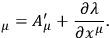

's among themselves as well as under “phase transformations”

's among themselves as well as under “phase transformations”

where

where

is an arbitrary function of the

is an arbitrary function of the

's, The “covariance” of the theory is described by an additional transformation group under which the equations of motion remain invariant, whose infinitesimal elements have the general form

's, The “covariance” of the theory is described by an additional transformation group under which the equations of motion remain invariant, whose infinitesimal elements have the general form

, where

, where

|

The

,

,

,

,

are certain definite functions of the

are certain definite functions of the

's, while the

's, while the

are arbitrary infinitesimal functions of the time and of the

are arbitrary infinitesimal functions of the time and of the

's and any of their time derivatives. Such a transformation may be called a gauge transformation; in general relativity it is an infinitesimal coordinate transformation, the

's and any of their time derivatives. Such a transformation may be called a gauge transformation; in general relativity it is an infinitesimal coordinate transformation, the

being the metric field variables.

being the metric field variables.

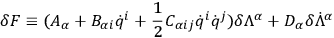

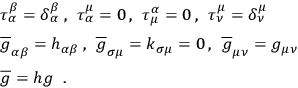

The Lagrangian function must be altered under a gauge transformation by a total time derivative

. It is not hard to see that

. It is not hard to see that

must have the general form

must have the general form

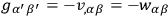

|

where the

,

,

,

,

,

,

are functions of the

are functions of the

's only. DE WITT

's only. DE WITT  , as this simplifies the analysis in certain respects. This assumption is actually incorrect for the gravitational field, but is not expected to alter the main qualitative features of the analysis. (It will be discussed more fully at a later point.) By performing a gauge transformation on the Lagrangian and making a comparison with

, as this simplifies the analysis in certain respects. This assumption is actually incorrect for the gravitational field, but is not expected to alter the main qualitative features of the analysis. (It will be discussed more fully at a later point.) By performing a gauge transformation on the Lagrangian and making a comparison with

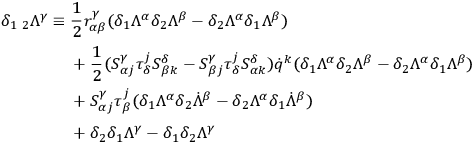

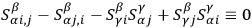

one finds that the following identities must be satisfied:

one finds that the following identities must be satisfied:

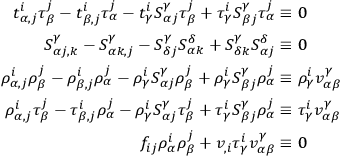

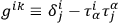

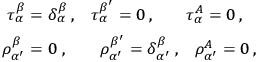

|

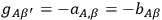

DE WITT

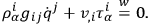

It is the identity

which shows that (

which shows that (

) must be a singular matrix in a “gauge invariant” theory. This has the consequence that the momenta of the Hamiltonian formalism are not all independent. It also has the consequence that the initial conditions on the motion must be subject to constraints

) must be a singular matrix in a “gauge invariant” theory. This has the consequence that the momenta of the Hamiltonian formalism are not all independent. It also has the consequence that the initial conditions on the motion must be subject to constraints  an extremum. Some, at least, of these constraints are obtained by multiplying the equations of motion by

an extremum. Some, at least, of these constraints are obtained by multiplying the equations of motion by

. Using identities of invariance one finds

. Using identities of invariance one finds

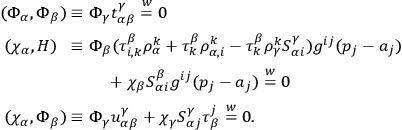

|

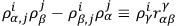

These will constitute the complete set of constraints

DE WITT  form a complete and independent set of null eigenvectors of

form a complete and independent set of null eigenvectors of

. One may then infer that

. One may then infer that

|

where the

,

,

,

,

are certain coefficients. DE WITT

are certain coefficients. DE WITT

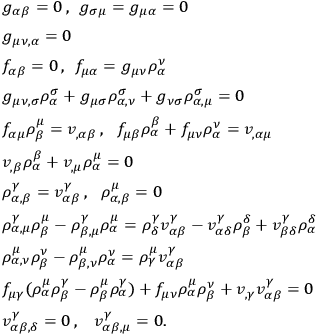

A final set of identities are obtained from the group property of gauge transformations. Requiring that the difference between the results of applying two infinitesimal gauge transformations in different orders be also a gauge transformation (of the second infinitesimal order) one finds

|

where

|

only if

|

for certain coefficients

, and if

, and if

|

where the

are certain coefficients satisfying

are certain coefficients satisfying

|

DE WITT

|

DE WITT  ) and strong equations (

) and strong equations (

). Equations of motion and constraints

). Equations of motion and constraints  ) are strong equations. Also, the product of two weakly vanishing functions is strongly equal to zero.

) are strong equations. Also, the product of two weakly vanishing functions is strongly equal to zero.

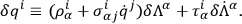

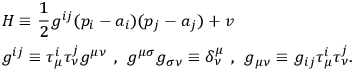

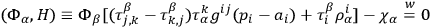

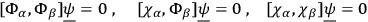

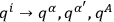

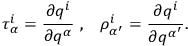

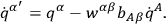

The canonical momenta for the system are

|

Multiplication by

gives immediately the set of constraints

gives immediately the set of constraints

|

Completing the set of vectors

through the introduction of a set of independent vectors

through the introduction of a set of independent vectors

, and introducing also “inverses”

, and introducing also “inverses”

,

,

satisfying

satisfying

, one may write the “energy function” in the form

, one may write the “energy function” in the form

|

where

|

The final expression for the energy function provides an illustration of Dirac's theorem  of the

of the

's and

's and

's, which may be called the Hamiltonian function, plus a linear combination of the

's, which may be called the Hamiltonian function, plus a linear combination of the

's with coefficients which depend on the velocities

's with coefficients which depend on the velocities

. In a theory without constraints the energy is identical with the Hamiltonian function. When constraints are present the two are only weakly equal.

. In a theory without constraints the energy is identical with the Hamiltonian function. When constraints are present the two are only weakly equal.

If the coefficients multiplying the

's are completely undetermined by the equations of motion, and hence completely arbitrary, the

's are completely undetermined by the equations of motion, and hence completely arbitrary, the

's are said to be “of the first class.” This point always requires special investigation. Using the equations of motion together with the constraints

's are said to be “of the first class.” This point always requires special investigation. Using the equations of motion together with the constraints  of the

of the

's and

's and

's is given by

's is given by

|

where

denotes the Poisson bracket. In particular, the time rate of change of a

denotes the Poisson bracket. In particular, the time rate of change of a

is given by

is given by

|

Since the

's vanish their time derivatives must also vanish. This will happen automatically if the Poisson brackets

's vanish their time derivatives must also vanish. This will happen automatically if the Poisson brackets

and

and

vanish, at least weakly. If these Poisson brackets do not all vanish then the

vanish, at least weakly. If these Poisson brackets do not all vanish then the

cannot all be completely arbitrary and the

cannot all be completely arbitrary and the

will be subject to additional constraints.

will be subject to additional constraints.

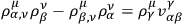

Using the relation

together with identities of invariance, one finds, after a straightforward computation,

together with identities of invariance, one finds, after a straightforward computation,

|

where

|

The latter equations are simply the velocity constraints  -equations, existing only in the canonical formalism, are sometimes known as “primary constraints.” The

-equations, existing only in the canonical formalism, are sometimes known as “primary constraints.” The

-equations, which follow from them, are then called “secondary constraints.” The

-equations, which follow from them, are then called “secondary constraints.” The

's as well as the

's as well as the

's must have vanishing time

derivatives. This leads one to investigate also the Poisson brackets

's must have vanishing time

derivatives. This leads one to investigate also the Poisson brackets

.

.

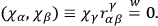

Using only the identities of invariance and completeness one finds

|

The vanishing (in the weak sense) of all these Poisson brackets means that

there exist no further constraints  's are all of the first class. There still remains, however, one further Poisson bracket which it is necessary to examine, namely

's are all of the first class. There still remains, however, one further Poisson bracket which it is necessary to examine, namely

. Dirac

. Dirac

In the evaluation of

identities of integrability are needed for the first time. One finds

identities of integrability are needed for the first time. One finds

|

Evidently Dirac brackets are here the same as ordinary Poisson brackets. Under these circumstances the

's are said to be “of the first class.” It is characteristic of any theory in which the constraints

's are said to be “of the first class.” It is characteristic of any theory in which the constraints  's and

's and

's are of the first class.

's are of the first class.

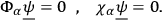

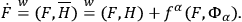

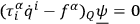

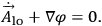

DE WITT

DE WITT  and

and

equations, which, in the quantum theory, are to be regarded as supplementary conditions on the state vector

equations, which, in the quantum theory, are to be regarded as supplementary conditions on the state vector

of the system:

of the system:

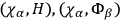

|

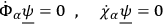

Since the classical expressions for the

and

and

involve quantities which, in the quantum theory, do not commute, the factor ordering problem here makes its appearance. According to DE WITT

involve quantities which, in the quantum theory, do not commute, the factor ordering problem here makes its appearance. According to DE WITT  and

and

should be taken as

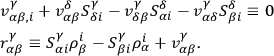

should be taken as

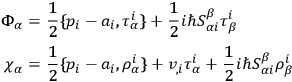

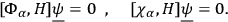

|

where

denotes the anticommutator bracket. With the aid of the previously unused identities of integrability one may then show that

denotes the anticommutator bracket. With the aid of the previously unused identities of integrability one may then show that

|

where

denotes the commutator bracket and where the ordering of factors

on the right is now important. Since the

denotes the commutator bracket and where the ordering of factors

on the right is now important. Since the

's and

's and

's all stand to the extreme right the corollaries

's all stand to the extreme right the corollaries

|

of the supplementary conditions are automatically satisfied. DE WITT  above) which are proportional to

above) which are proportional to

or powers of

or powers of

, and which do not appear in the corresponding classical expression (since

, and which do not appear in the corresponding classical expression (since

).

).

Similar considerations are involved in finding the quantum analog of the

function

. It is convenient to return for a moment to the classical theory: Since the

. It is convenient to return for a moment to the classical theory: Since the

's and

's and

's are all of the first class, the quantities

's are all of the first class, the quantities

appearing in the dynamical equation (i.e., for

appearing in the dynamical equation (i.e., for

) are completely arbitrary. One is at liberty to set them equal to arbitrary functions

) are completely arbitrary. One is at liberty to set them equal to arbitrary functions

of the

of the

's and

's and

's through the addition of

extra supplementary conditions:

's through the addition of

extra supplementary conditions:

|

The energy function

is then strongly equal to

is then strongly equal to

|

Furthermore, the dynamical equation may be replaced by

|

The conditions

,

,

are, of course, unaffected.

are, of course, unaffected.

In the quantum theory the dynamical equation may be taken as

|

in which the quantum form of

is written as above with the

is written as above with the

's standing to the right. The time derivatives of the supplementary conditions, namely

's standing to the right. The time derivatives of the supplementary conditions, namely

|

will then be satisfied provided

|

The quantum form of

will be chosen in such a way that these equations are automatically satisfied by virtue of the supplementary conditions. The supplementary

conditions when combined with the dynamical equations for

will be chosen in such a way that these equations are automatically satisfied by virtue of the supplementary conditions. The supplementary

conditions when combined with the dynamical equations for

will generally imply

will generally imply

|

where

indicates some suitable quantum analog for

indicates some suitable quantum analog for

, and in this way the consistency of the quantum scheme can be checked for arbitrary choices of the

, and in this way the consistency of the quantum scheme can be checked for arbitrary choices of the

.

.

It is to be noted that one is here working in the Heisenberg picture in which the state vector

is time independent. The arbitrariness in the choice of

the functions

is time independent. The arbitrariness in the choice of

the functions

shows that there are many different Heisenberg pictures, all equally valid. They all lead, however, to a single unique Schrödinger picture:

shows that there are many different Heisenberg pictures, all equally valid. They all lead, however, to a single unique Schrödinger picture:

|

One may arrive directly at the Schrödinger picture by starting, in the classical theory, from the “homogeneous velocity” formalism (Dirac,  . This leads to a new

. This leads to a new

equation, namely

equation, namely

where

where

. In the quantum theory, representation of

. In the quantum theory, representation of

puts the corresponding condition on the state vector in the form

puts the corresponding condition on the state vector in the form

|

which is just the Schrödinger equation.

Construction of the quantum form of

is more difficult than the construction of the quantum forms of

is more difficult than the construction of the quantum forms of

and

and

for two reasons: (1)

for two reasons: (1)

is quadratic rather than linear in the momenta. (2) No metric has yet been defined in

is quadratic rather than linear in the momenta. (2) No metric has yet been defined in

-space. If there were no gauge transformation group for the system,

-space. If there were no gauge transformation group for the system,

would be nonsingular and

would, as DE WITT

would be nonsingular and

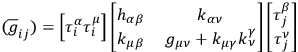

would, as DE WITT  as a sort of superstructure with

as a sort of superstructure with

as a core, in the following manner:

as a core, in the following manner:

|

matrix multiplication as indicated, where

,

,

are arbitrary functions of the

are arbitrary functions of the

's. However,

's. However,

is assumed to have an inverse

is assumed to have an inverse

which is used to raise the indices

which is used to raise the indices

,

,

,

,

, etc., while

, etc., while

is used to raise the indices

is used to raise the indices

,

,

,

,

, etc. (

, etc. (

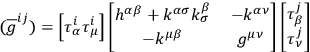

) will then have an inverse given by

) will then have an inverse given by

|

and a determinant given by

|

where

,

,

,

,

. The metric

. The metric

may be used to make a special choice for the function

may be used to make a special choice for the function

, namely

, namely

|

corresponding to the choice

|

The equations of motion generated by this “Hamiltonian” may be derived from a Lagrangian function of the form

|

The quantum theory generated by this Lagrangian function is not identical with that which has been developed here, but becomes so upon the addition of the equations

as supplementary conditions. This is a standard procedure in quantum electrodynamics in which these supplementary conditions become the “Lorentz

conditions.”

as supplementary conditions. This is a standard procedure in quantum electrodynamics in which these supplementary conditions become the “Lorentz

conditions.”

A choice of metric having been adopted, one may now express the quantized momenta explicitly in the form

|

and one finds that the supplementary conditions become

|

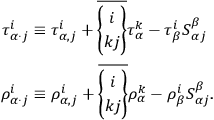

a dot followed by an index denoting covariant differentiation with respect to the metric

, with, however, the modification

, with, however, the modification

|

being the Christoffel symbol

being the Christoffel symbol  . A special significance possessed by the coefficients

. A special significance possessed by the coefficients

is here emphasized. The

is here emphasized. The

provide a kind of affine connection in terms of which one may define parallel displacements which are invariant not only under point transformations but also under transformations associated with the indices

provide a kind of affine connection in terms of which one may define parallel displacements which are invariant not only under point transformations but also under transformations associated with the indices

,

,

, etc., of the form

, etc., of the form

|

where the

are arbitrary functions of the

are arbitrary functions of the

's, the matrix (

's, the matrix (

) possessing, however, an inverse (

) possessing, however, an inverse (

). These transformations, which DE WITT

). These transformations, which DE WITT  -transformations, leave all the identities of invariance, completeness, and integrability unchanged. The

-transformations, leave all the identities of invariance, completeness, and integrability unchanged. The

-transformation procedure may be extended to the indices

-transformation procedure may be extended to the indices

,

,

,

,

, etc., by the definitions

, etc., by the definitions

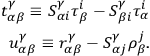

|

where the

,

,

are also arbitrary functions of the

are also arbitrary functions of the

's, with (

's, with (

) possessing as an inverse (

) possessing as an inverse (

). The whole theory (in particular, the metric

). The whole theory (in particular, the metric

) will then

be invariant under

) will then

be invariant under

-transformations provided

-transformations provided

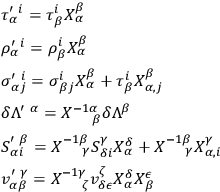

|

In order to show the invariance of the quantum theory under point, phase, gauge, and

-transformations one does not actually have to use the differential representation of the momenta, convenient though it generally is. For example, the

point transformation law for the momenta is

-transformations one does not actually have to use the differential representation of the momenta, convenient though it generally is. For example, the

point transformation law for the momenta is

|

and, remembering that the indices

etc., on the quantities

etc., on the quantities

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

, etc., are all tensor indices under point transformations, one finds by

straightforward computation that

, etc., are all tensor indices under point transformations, one finds by

straightforward computation that

,

,

,

,

, provided one writes

, provided one writes

|

where

is a scalar function of the

is a scalar function of the

's, as yet undetermined. Similarly, under

's, as yet undetermined. Similarly, under

-transformations one finds

-transformations one finds

and

and

|

Since the

's and

's and

's stand to the right the supplementary conditions remainunchanged:

's stand to the right the supplementary conditions remainunchanged:

,

,

. Invariance of the quantum theory under gauge

transformations is not immediately apparent at this point, but becomes so subsequently. Phase transformations, on the other hand, are trivial:

. Invariance of the quantum theory under gauge

transformations is not immediately apparent at this point, but becomes so subsequently. Phase transformations, on the other hand, are trivial:

|

or, if one is using the fixed differential representation for the momenta, one places the burden of keeping the theory phase-invariant on the state vector (or wave function) by the law

|

Having introduced

-transformations, DE WITT

-transformations, DE WITT  satisfies the very important condition of being integrable. This

means that one can carry out an

satisfies the very important condition of being integrable. This

means that one can carry out an

-transformation which will make the

-transformation which will make the

vanish everywhere. The required transformation is given by the solutions of the simultaneous equations

vanish everywhere. The required transformation is given by the solutions of the simultaneous equations

|

The solubility of these equations is guaranteed by the identity of integrability

. After this transformation has been carried out one has

. After this transformation has been carried out one has

|

which implies that there exists a point transformation

such that

such that

|

Making this point transformation, together with an additional

-transformation

-transformation

|

and letting the

be given by

be given by

|

one arrives at a great simplification in the formalism. Using a simple replacement of indices

;

;

, etc., to denote quantities in the new “coordinate system,” one has

, etc., to denote quantities in the new “coordinate system,” one has

|

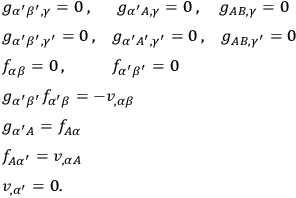

Moreover, the identities of invariance and integrability take the forms

|

The identity

implies that a phase transformation (

implies that a phase transformation (

) can be

carried out which makes

) can be

carried out which makes

vanish. Assuming that it has already been performed and noting that

vanish. Assuming that it has already been performed and noting that

|

one may now write the supplementary condition in the forms

|

The first supplementary condition has the important result that the arbitrary quantities

can now be actually eliminated entirely from the quantum theory, just as they are not needed in the classical theory. That is, having carefully built up a “superstructure” around the metric

can now be actually eliminated entirely from the quantum theory, just as they are not needed in the classical theory. That is, having carefully built up a “superstructure” around the metric

(or

(or

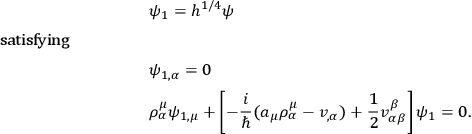

), one then proceeds to throw it away. To do this one simply introduces a new wave function

), one then proceeds to throw it away. To do this one simply introduces a new wave function

|

This definition removes from the wave function that part of the metric density which refers exclusively to the

, and corresponds to the use of

, and corresponds to the use of

as invariant volume element. The condition

as invariant volume element. The condition

means that the new wave function does not depend on the variables

means that the new wave function does not depend on the variables

. The

. The

are non-observable or “non-physical” variables of the system. This was, in fact, already true in the classical theory, since the

are non-observable or “non-physical” variables of the system. This was, in fact, already true in the classical theory, since the

can be made to undergo arbitrary changes by means of gauge transformations.

can be made to undergo arbitrary changes by means of gauge transformations.

In the new representation

by itself provides a natural metric in the reduced space of the

by itself provides a natural metric in the reduced space of the

. To see how this works for the Hamiltonian operator, one can multiply the Schrödinger equation

. To see how this works for the Hamiltonian operator, one can multiply the Schrödinger equation

|

by

. Using the explicit form for

. Using the explicit form for

, one finds, after a straightforward calculation,

, one finds, after a straightforward calculation,

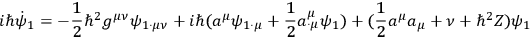

|

where the dots now denote covariant differentiation with respect to the metric

, and where

, and where

|

The quantity

is invariant under point transformations which are restricted to the variables

is invariant under point transformations which are restricted to the variables

alone.

alone.

The new Schrödinger equation may be written in the form

|

where

|

the explicit differential form for the momenta

in the new representation being

in the new representation being

|

The existence of the second supplementary condition suggests that there are further non-physical variables in addition to the

. To show this one must first

eliminate the term in

. To show this one must first

eliminate the term in

from the supplementary condition. This can be done by carrying out a phase transformation

from the supplementary condition. This can be done by carrying out a phase transformation

satisfying

satisfying

|

and at the same time satisfying

|

so as not to disturb the condition

. The integrability of these equations is insured by the identities of invariance and integrability, as one may verify by

straightforward computation, showing that the expressions for

. The integrability of these equations is insured by the identities of invariance and integrability, as one may verify by

straightforward computation, showing that the expressions for

and

and

vanish. One may then write

vanish. One may then write

|

Next, by differentiating the identity

one can show that

one can show that

|

The coefficients

are then immediately recognizable as the structure constants

of a Lie group. The secondary constraints

are then immediately recognizable as the structure constants

of a Lie group. The secondary constraints  are, in fact, the infinitesimal generators of the group. In the general case the structure constants will be

non-vanishing and the Lie group will be non-Abelian. This immediately leads one to various possibilities depending on the classification of the Lie group in question. As an illustration, suppose that the Lie group is the irreducible rotation group in

are, in fact, the infinitesimal generators of the group. In the general case the structure constants will be

non-vanishing and the Lie group will be non-Abelian. This immediately leads one to various possibilities depending on the classification of the Lie group in question. As an illustration, suppose that the Lie group is the irreducible rotation group in

dimensions. The indices

dimensions. The indices

must then range over

must then range over

different values. This is not however the number of further non-physical variables. A point transformation

different values. This is not however the number of further non-physical variables. A point transformation

can

be made such that the new variables

can

be made such that the new variables

describe the subspace in which the rotations actually take place. The quantity

describe the subspace in which the rotations actually take place. The quantity

vanishes for the rotation group and the second supplementary condition is found to reduce to

vanishes for the rotation group and the second supplementary condition is found to reduce to

which, when analyzed, is seen to state simply that the wave function is invariant under rotations in the subspace of the

which, when analyzed, is seen to state simply that the wave function is invariant under rotations in the subspace of the

. Therefore, in this case only

. Therefore, in this case only

further variables can be eliminated from the theory as non-physical. The wave function can still depend on the rotation-invariant combination

further variables can be eliminated from the theory as non-physical. The wave function can still depend on the rotation-invariant combination

as well as on the

as well as on the

.

.

The primary constraints  also, of course, generate a Lie group. But this group is necessarily Abelian.

DE WITT

also, of course, generate a Lie group. But this group is necessarily Abelian.

DE WITT  is also Abelian (so that

is also Abelian (so that

) and furthermore that the vectors

) and furthermore that the vectors

are linearly independent of the

are linearly independent of the

and of each other. In this case, when

and of each other. In this case, when

, one may carry out a point transformation

, one may carry out a point transformation

such that

such that

|

(Here, in order to avoid confusion one must use a prime to distinguish indices related to the

from those related to the

from those related to the

.) In the new “coordinate system” one has

.) In the new “coordinate system” one has

|

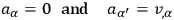

and the identities of invariance and integrability become

|

If the phase is adjusted so that

|

then one also has

|

Moreover, the supplementary conditions become

|

so that the

, like the

, like the

, are now “non-physical” variables.

, are now “non-physical” variables.

The quantity

is seen to be independent of the

is seen to be independent of the

and to have a dependence on the

and to have a dependence on the

which is no more than quadratic (since

which is no more than quadratic (since

). One may choose the origin of the unobservable “coordinates”

). One may choose the origin of the unobservable “coordinates”

in such a way that

in such a way that

|

where

and

and

are independent of the

are independent of the

and

and

. Furthermore, since

. Furthermore, since

and

and

, one may write

, one may write

|

where

and

and

are independent of the

are independent of the

and

and

. In order to complete the elimination of the

. In order to complete the elimination of the

from the theory, a natural metric

from the theory, a natural metric

for the reduced space of the

for the reduced space of the

must be introduced. DE WITT showed that it must be defined in the following manner:

must be introduced. DE WITT showed that it must be defined in the following manner:

|

in which use has been made of the relations

,

,

, and in which the matrix (

, and in which the matrix (

) is assumed to have an inverse (

) is assumed to have an inverse (

).

).

With this definition one has

and

and

|

where

and

and

. The determinant

. The determinant

forms that part of the metric density

forms that part of the metric density

which refers exclusively to the non-physical variables

which refers exclusively to the non-physical variables

. It may be removed from the normalization of the wave function

. It may be removed from the normalization of the wave function

by introducing a new wave function

by introducing a new wave function

|

Since

,

,

,

,

is independent of the

is independent of the

and

and

. It may becalled the “true physical wave function” of the system referring only to the “physical” variables

. It may becalled the “true physical wave function” of the system referring only to the “physical” variables

. Its Schrödinger equation may be found by multiplying the

Schrödinger equation

. Its Schrödinger equation may be found by multiplying the

Schrödinger equation

by

by

making use of the relations

making use of the relations

|

One finds, after a straightforward computation,

|

where

|

The operator

remains invariant under point transformations which are restricted to the variables

remains invariant under point transformations which are restricted to the variables

alone.

alone.

The operators

,

,

and any quantities constructed out of them are the true observables

and any quantities constructed out of them are the true observables

|

One has only to require that

be independent of the

be independent of the

and

and

.

.

will then be a true observable

will then be a true observable and

and

) and the wave function

) and the wave function

will remain independent of the

will remain independent of the

and

and

at all times.

at all times.

The gauge invariance of the quantum theory is now also

immediately evident. In the “coordinate” system

,

,

,

,

, gauge transformations are given simply by

, gauge transformations are given simply by

|

and hence

|

There remains only the term

which is unknown. However this term, as Feynman

which is unknown. However this term, as Feynman in the limit, and this is arbitrary.

in the limit, and this is arbitrary.

It is of interest to examine the Feynman quantization only, using the measure defined by the metric

only, using the measure defined by the metric

. The variables

. The variables

may be chosen as arbitrary functions of the time (corresponding to the original arbitrariness in the

may be chosen as arbitrary functions of the time (corresponding to the original arbitrariness in the

) and the original Lagrangian function

) and the original Lagrangian function

may be used to compute the action, provided the variables

may be used to compute the action, provided the variables

are made to vary in time in such a way as to satisfy the velocity constraints

are made to vary in time in such a way as to satisfy the velocity constraints

|

or

|

For the Lagrangian function then becomes

|

which is precisely the form which gives rise to the Hamiltonian

. One may therefore express the transformation function in the symbolic form

. One may therefore express the transformation function in the symbolic form

|

with the understanding that the functional integration  and

and

which satisfy the velocity constraints

which satisfy the velocity constraints  given, each path being assigned a weight according to the measuredefined by

given, each path being assigned a weight according to the measuredefined by

. (Here, potential-like terms proportional to

. (Here, potential-like terms proportional to

, which may be added to

, which may be added to

, are ignored.)

, are ignored.)

It is not actually necessary to restrict the summation to the variables

only. For example, one may work with the transformation function

only. For example, one may work with the transformation function

|

which connects the values of the wave function

at two different times. Since

at two different times. Since

is independent of the

is independent of the

for physical states, one may write

for physical states, one may write

|

which implies

|

The expression on the right must be independent of the

. Hence one may integrate over these variables provided one divides the result by an infinite normalization factor. Moreover, in the path summation expression for

. Hence one may integrate over these variables provided one divides the result by an infinite normalization factor. Moreover, in the path summation expression for

the choice of time-like behavior for the variables

the choice of time-like behavior for the variables

is immaterial. Hence one may write

is immaterial. Hence one may write

|

where

is a suitable infinite normalization factor, the functional integration

is a suitable infinite normalization factor, the functional integration  ,

,

at

at

,

,

respectively (all possible end-point values for the variables

respectively (all possible end-point values for the variables

,

,

being included in the summation) each path being given a weight according to the measure defined by metric density

being included in the summation) each path being given a weight according to the measure defined by metric density

multiplied by the Jacobian of the transformation

multiplied by the Jacobian of the transformation

,

,

,

,

. In calculation of actual physical quantities one never needs to mention the normalization factor

. In calculation of actual physical quantities one never needs to mention the normalization factor

explicitly, since what is involved is always a ratio of the form

explicitly, since what is involved is always a ratio of the form

|

where

is some true observable

is some true observable ,

,

alone), and the normalization factors in front of the functional integrals cancel.

alone), and the normalization factors in front of the functional integrals cancel.

DE WITT  , occurring in the expression for

, occurring in the expression for

, vanish. In the case of the Lagrangian for the gravitational field the

, vanish. In the case of the Lagrangian for the gravitational field the

do not vanish. This has the result that the secondary constraints

do not vanish. This has the result that the secondary constraints  are no longer linear in the momenta, but quadratic. In fact, it had been pointed out earlier in the conference that the quadratic term, in the gravitational case, is just the energy density for the gravitational field. This created a certain amount of perplexity, leading some of the participants to think that perhaps all true observables

are no longer linear in the momenta, but quadratic. In fact, it had been pointed out earlier in the conference that the quadratic term, in the gravitational case, is just the energy density for the gravitational field. This created a certain amount of perplexity, leading some of the participants to think that perhaps all true observables will be considerably more difficult in the case

will be considerably more difficult in the case

.

The resulting quadratic dependence of the

.

The resulting quadratic dependence of the

on the momenta means that the non-physical variables can no longer be found simply by a point transformation. A more complicated type of canonical transformation will be required.

on the momenta means that the non-physical variables can no longer be found simply by a point transformation. A more complicated type of canonical transformation will be required.

DE WITT suggested that the use of parametrized space-like surfaces might help this situation. But he also pointed out that the equations like

become variational differential equations

in field equations in field theories, and that there is some uncertainty about the ease with which they can be solved in nonlinear contexts. The search for answers to these questions will provide a large program for the future.

become variational differential equations

in field equations in field theories, and that there is some uncertainty about the ease with which they can be solved in nonlinear contexts. The search for answers to these questions will provide a large program for the future.

FEYNMAN

LICHNEROWICZ

“(1) It may be simpler to consider directly the configuration space-time of the system, i.e., to treat

as a local coordinate. Let

as a local coordinate. Let

be the configuration space-time.

be the configuration space-time.

“(2) The geometrical frame is then the fiber bundle space of

dimensions - say

dimensions - say

- consisting of the tangents of

- consisting of the tangents of

at all points.

at all points.

“(3) The gauge transformations have, for infinitesimal generators, vector fields

of

of

. The precise hypothesis for the Lie algebra of the

. The precise hypothesis for the Lie algebra of the

fields is the following:

fields is the following:

can be decomposed into a direct sum

can be decomposed into a direct sum

where

where

is a tangent to the fibers. This decomposition is such that

is a tangent to the fibers. This decomposition is such that

depends on the points of

depends on the points of

only, and

only, and

depends linearly on the directions.

depends linearly on the directions.

defines a field of plane surfaces on which the pseudo-metric

defines a field of plane surfaces on which the pseudo-metric

vanishes.

vanishes.

“(4) By introducing an extra dimension, one can have a Lagrangian corresponding to a Riemannian pseudo-metric (degenerate quadratic form), and it seems that the explicit calculations in the classical part could then be simplified.”

ANDERSON and LAURENT

The chief difficulty in this procedure rests in the fact, of course, that one of the equations of motion for the field is free of second time derivatives and therefore represents a restriction on initial and final values which one may impose on the field conditions. However, if one transforms to a set of field variables which include

,

,

, and the scalar field

, and the scalar field

, then the equations of constraint do not depend on

, then the equations of constraint do not depend on

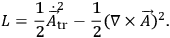

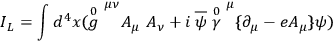

. In fact, the Lagrangian originally looks like

. In fact, the Lagrangian originally looks like

|

and the equations of constraint appear as

|

so in terms of

,

,

,

,

equations of constraint

equations of constraint

|

Thus solutions satisfying all field equations yield for

|

Thus the construction of the Feynman integral is then seen to be in terms of

alone, and the measure is given uniquely by the Lagrangian - in this case simply 1.

alone, and the measure is given uniquely by the Lagrangian - in this case simply 1.

If one were to extend this line of reasoning to the gravitational case, it is seen that one must look for a set of variables which have the property that they do not appear in the constraint  which corresponds in the electromagnetic case to the scalar potentials. The elimination of the longitudinal part of the gravitational field is of course a much more difficult

problem and has in no way been solved as yet, although it appears to be the central problem to the quantization.”

which corresponds in the electromagnetic case to the scalar potentials. The elimination of the longitudinal part of the gravitational field is of course a much more difficult

problem and has in no way been solved as yet, although it appears to be the central problem to the quantization.”

LAURENT

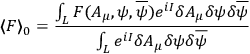

“In the following I wish to explain why I think that it is worthwhile to try Feynman's action method

I shall start with the simplest generally covariant theory known, that is electrodynamics, which is covariant with respect to gauge transformations.

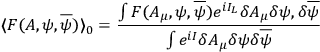

Feynman's

|

21.1 |

Here

is the action-functional for the fields (or field) and all

is the action-functional for the fields (or field) and all

stand for the field-functions in the

stand for the field-functions in the

space-time points

space-time points

. The integrals are functional integrals over the functions in all space-time, performed after a certain small imaginary term has been added to the action (as Burton and DeBorde show, this picks out a vacuum state). An extended class of operators may be constructed as sums of time-ordered products

. The integrals are functional integrals over the functions in all space-time, performed after a certain small imaginary term has been added to the action (as Burton and DeBorde show, this picks out a vacuum state). An extended class of operators may be constructed as sums of time-ordered products

. To be general I shall in the following write

. To be general I shall in the following write

instead of

instead of

in (21.1).

in (21.1).

is here a functional of the fields

is here a functional of the fields

.

.

In the usual Lorentz-gauge electrodynamics a vacuum propagator is to be written as follows:

|

21.2 |

A special device must here be used to obtain the wanted anticommuting properties of

,

,

7

7

|

21.3 |

where

is the Lorentz-metric and

is the Lorentz-metric and

the Dirac-matrices.

the Dirac-matrices.

(21.2) is exactly the ordinary vacuum propagator of electrodynamics if we restrict

so that we have nothing but electrons and transversal photons in the initial and final states.8

so that we have nothing but electrons and transversal photons in the initial and final states.8

may for instance have the following form:

may for instance have the following form:

|

21.4 |

Here

is a normalizing factor

is a normalizing factor

and

and

.

.

The operator corresponding to (21.4) gives merely transversal photons in the initial and end states of the propagator.

Observe that in a gauge-transformation

|

21.5 |

in (21.4) is invariant. We shall assume throughout that our

in (21.4) is invariant. We shall assume throughout that our

's have this property.

's have this property.

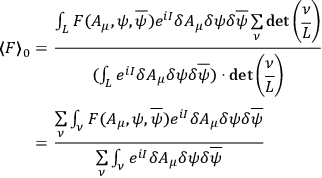

Let us now re-form (21.2)

|

21.6 |

We have split up the integrals over all possible

-functions in sums of integrals over part-regions, of which the first is around the

-functions in sums of integrals over part-regions, of which the first is around the

-functions satisfying the Lorentz-condition. The other regions are obtained from the Lorentz-region by gauge-transformations. The regions cover completely the region of all

-functions satisfying the Lorentz-condition. The other regions are obtained from the Lorentz-region by gauge-transformations. The regions cover completely the region of all

-functions and they do not overlap. The part-regions can be made as narrow as we like.

-functions and they do not overlap. The part-regions can be made as narrow as we like.

Remembering that

is invariant and that the gauge-transformation is linear we see that the following is true:

is invariant and that the gauge-transformation is linear we see that the following is true:

|

21.7 |

is the complete gauge-invariant action

is the complete gauge-invariant action

|

21.8 |

is the Jacobian of the transformation from the

is the Jacobian of the transformation from the

-th region to the Lorentz-region. In this case

-th region to the Lorentz-region. In this case

is 1 but we shall keep it in in spite of that to be able to use the result later in gravitation theory.

is 1 but we shall keep it in in spite of that to be able to use the result later in gravitation theory.

We may now write

|

21.9 |

depends on the region only (when the region is narrow). In the Lorentz-region,

depends on the region only (when the region is narrow). In the Lorentz-region,

. Hence

. Hence

|

21.10 |

Further we see that

|

21.11 |

|

21.12 |

From this form it is evident that the propagator is invariant.

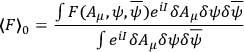

We see from this that under the supposition made about

, that it must not change its form when

, that it must not change its form when

is replaced by

is replaced by

, the two demands are fulfilled that quantization shall, as in (21.10), be performed over the “real degrees of freedom” only and that the procedure shall be covariant as in (21.12).

, the two demands are fulfilled that quantization shall, as in (21.10), be performed over the “real degrees of freedom” only and that the procedure shall be covariant as in (21.12).

According to the foregoing it is close at hand to guess that a propagator in a theory that is covariant with respect to linear transformation shall be written in the form (21.12), where

and

and

must be invariant in the sense mentioned above9

must be invariant in the sense mentioned above9

10 (in the general case we call it extended gauge-invariance). If in gravitation theory, for instance,

10 (in the general case we call it extended gauge-invariance). If in gravitation theory, for instance,

is a functional of the

is a functional of the

only it must not change its form in the linear transformation

only it must not change its form in the linear transformation

,where

,where

is an arbitrary (non-singular) transformation. We observe that a scalar does not necessarily fulfill the requirement, because, in general, it changes its functional form of

is an arbitrary (non-singular) transformation. We observe that a scalar does not necessarily fulfill the requirement, because, in general, it changes its functional form of

in the transformation. If

in the transformation. If

is a function as here described and the integration variables transform linearly, we see from the procedure followed in the electromagnetic case that we may always come from the covariant propagator of type (21.12) to the propagator of type (21.10) , where only so much of the field is quantized as there are “degrees of freedom.”11

is a function as here described and the integration variables transform linearly, we see from the procedure followed in the electromagnetic case that we may always come from the covariant propagator of type (21.12) to the propagator of type (21.10) , where only so much of the field is quantized as there are “degrees of freedom.”11

A difficulty in the gravitation case is that we do not know over which variables we ought to integrate, and which measure should be chosen in the functional integral.12

The choice of integration variables that seem most natural at first sight is perhaps that of the

or

or

, but as Professor J. A. Wheeler

, but as Professor J. A. Wheeler

(MISNER

Finally I should like to say a few words about how functionals of the type mentioned earlier may be constructed in gravidynamics.13 Integrals of scalar densities over all space-time is of this type but they do not seem to be of much use in this connection. Professor O. Klein has pointed out to me that the total energy-momentum pseudo-vector may be useful here, and in fact we see that it is of the correct type if we choose it in the following form:

|

21.13 |

(I do not think that this formula needs any explanation.)

is identically satisfied which gives (21.13) the desired property for

is identically satisfied which gives (21.13) the desired property for

-transformations which are identity-transformations on the boundaries of the integration-volume. Now all the propagators in the foregoing are limits when the space-time region involved becomes infinitely large14 and nothing hinders us from prescribing, for instance, the Lorentz-metric outside the region and on its boundaries. This means that every interesting transformation is of the type mentioned. In this case the propagator is dependent on the boundary conditions chosen in infinity.”

-transformations which are identity-transformations on the boundaries of the integration-volume. Now all the propagators in the foregoing are limits when the space-time region involved becomes infinitely large14 and nothing hinders us from prescribing, for instance, the Lorentz-metric outside the region and on its boundaries. This means that every interesting transformation is of the type mentioned. In this case the propagator is dependent on the boundary conditions chosen in infinity.”

During the discussion which sandwiched and followed LAURENT's - FEYNMAN raised the difficulties brought in by the presence in

- FEYNMAN raised the difficulties brought in by the presence in

, of second derivatives.

, of second derivatives.

BELINFANTE

FEYNMAN defined by the equation

defined by the equation

)? More precisely, what is the expression of the determinant which gives a value to the path integral independent of the mesh introduced for its definition?

)? More precisely, what is the expression of the determinant which gives a value to the path integral independent of the mesh introduced for its definition?

WHEELER in electrodynamics) and of the true (or physical) variables (such as

in electrodynamics) and of the true (or physical) variables (such as

). At present we have three schemes:

). At present we have three schemes:

– “Sum over fields” expressed in terms of latent variables. The infinities cancel out.

– Add a term to the Lagrangian so as to make the problem non-singular.

– Use only physical variables.

The whole art is working back and forth between latent and true variables. It is important to show the equivalence of the various schemes and to show the equivalence of the various “slicings,” but it is a task yet to be accomplished.

BERGMANN

One word about why the two approaches appear to lead to mutually consistent results in electrodynamics: in electrodynamics the components of the metric tensor, that is the second derivative of the Lagrangian with respect to the velocities, are constants. It appears natural that in such a situation there should be no disagreement; but I feel very doubtful, without availability of further strong arguments, about anticipating a similar agreement in general relativity, where the same coefficients are complicated functions of the field variables.

I think it is obvious to all of us that the difference between the two approaches again amounts to an estimate of the relative importance of true observables vs. all dynamical variables. Therefore, permit me to give one more argument

that indicates the probable importance of the true observables, or dynamical variables as John Wheeler

I would like to close with a comment on the motivation for Feynman quantization -number theory, and examining the intrinsic structure of a full-blown covariant

-number theory, and examining the intrinsic structure of a full-blown covariant

-number theory.”

-number theory.”

Footnotes

Feldquantisierung, lecture notes, Zürich, 1950-1951.

J. H. Van Vleck. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 14, 178 (1928); C. Morette. Phys. Rev. 81, 848 (1951).

Can. J. Math. 2, 129 (1950).

Nuovo Cimento IV, 1445 (1956).

R.P. Feynman: Rev. Mod. Phys. 20, 367 (1948).

P. T. Matthews, A. Salam: Nuov. Cim 2, 120 (1955); W. K. Burton, A. H. DeBorde: Nuov. Cim 4, 254 (1956); P. W. Higgs: Nuov. Cim 6, 1263 (1956).

Feynman, op. cit., and Burton and DeBorde, op. cit..

Switching off of the electron charge

is here assumed.

is here assumed.

This does not mean that we have no use for other types of

in intermediate calculations. In electrodynamics with truncated Lorentz-gauge action we may, for instance, calculate (21.2) with

in intermediate calculations. In electrodynamics with truncated Lorentz-gauge action we may, for instance, calculate (21.2) with

and that is very useful.

and that is very useful.

is not necessarily the classical action-functional for the system (also when such a functional exists), but it should go over into the classical function when

is not necessarily the classical action-functional for the system (also when such a functional exists), but it should go over into the classical function when

.

.

In electrodynamics this question is easily answered: Every gauge-invariant functional is of the wanted type. If the gravitational field constant is switched on and off, the matter can to some extent be made equally simple in gravidynamics.

Burton and DeBorde, op. cit.; Higgs, op. cit..

in (

in (