Chapter structure

- 2.1 Turin’s Economy and Politics between Italy and Europe

- 2.2 Civil Reforms and Military Policy

- 2.3 Engineering and Architecture

- 2.4 Intellectual Ferment: Arts, Literature, and Philosophy

- 2.5 Religious Policy

- 2.6 Cultural Institutions: University, Academies, Collections, and the Press

- 2.7 Scientific Debates

- 2.8 Strengths and Limitations of the Institutional Framework of Benedetti’s Science

- Footnotes

Benedetti’s life, work, and reception are indissolubly linked to Turin

Nineteen years have passed since I was sent for by a letter of the most serene [Emanuele Filiberto] father of Your Highness [Carlo Emanuele I ] and I moved from the town Parma to this municipality. Upon my arrival, he received me so humanely, and later I met with so much generosity as a reward for my services, that I began to desire vehemently that I could spend the rest of my life under his authority.1

As one reads, Benedetti and Emanuele Filiberto

His benevolence toward me, as well as my respect toward him, consolidated through the time we spent together, and our familiarity [grew] to the point that the duke wanted me to accompany him when he resided in the countryside. [He] often [even invited me] to stay with him overnight. In that time he discussed mathematics with me. He used my work in order to learn those sciences, asking questions on arithmetic, geometry, optics, music and astronomy [astrologia].2

Emanuele Filiberto’s

That Duke is no man of letters but he loves the virtuosi. Hence, he has many of them by him; he likes to listen to their reasoning and he asks them questions. However, there is no subject that delights him more than mathematics, as this science is not only apt but also necessary to the profession of military commander.3

Fig. 2.1: Portrait of Emanuele Filiberto from Tonso, De vita Emmanuelis Philiberti (1596). (Biblioteca Nazionale Universitaria di Torino)

The duke’s passion for science and his special relation with his court mathematician is further confirmed by the Venetian

The duke of Savoyhas a wonderful mind apt to every kind of science. However, he did not learn the sciences [le lettere] with the diligence that is necessary to become an expert, as his passion has always been the profession of war […]. But since mathematics is very useful and [even] necessary to professional warfare, His Excellency [Emanuele Filiberto ] learns [mathematics] with much pleasure and knows more of it than the average man. He is aware that to receive substantial knowledge in any science one has to be in contact with it and learn it continuously; therefore a certain Mr. Giovanni Battista Benedetti of Venice imparts to him a lesson either on Euclid or on another writer of those sciences every day. In my opinion, as well as according to many other gentlemen, he is the most excellent scholar in this discipline in our times. The duke likes him very much. In fact, not only has [Benedetti] mastered this science, but he is also able to transmit it very well to others in his lessons.4

However, Benedetti’s activities in Turin

2.1 Turin’s Economy and Politics between Italy and Europe

From the point of view of economic exchanges as well as of the European balance of power, Turin

Its intermediate position between Italy and France made the town relevant not only from the point of view of economics and culture but also for military reasons. When Francis I

Emanuele Filiberto

Turin

Within this difficult territorial and political constellation it was imperative that Emanuele Filiberto

International diplomacy was comprised of marriage politics. Emanuele Filiberto

Fig. 2.2: Portrait of Carlo Emanuele I by Francesco Maria Ferrero di Labriano, Augustae Regiaeque Sabaudae Domus Arbor Gentilitia (Turin, 1702), p. 174. (Biblioteca Nazionale Universitaria di Torino)

In his relations to other Italian States the duke also followed a politics of balance. He was particularly keen on having good relations with Venice

The ties with Rome

When Malta was besieged by the Turks, in June 1565, duke Emanuele [Filiberto]sent Andrea Provana of Leinì with four well-equipped triremes to bring supplies to the isle together with triremes from the Pope, Spain, and other [states]. First, Provana [Leniacus] arrived and assessed the difficulties. Then, he conveyed others [to the battle] and broke the siege with divine favor. The holy and vigorous order of the knights of Jerusalem was liberated under the superior command of the French Jean of Valetta . Public demonstrations of immense joy and pious celebrations of thanks to God for the victory were displayed in Turin .7

In 1571 Provana

In 1571, when duke Emanuele [Filiberto]ruled over Turin and a confederation was established between Pope Pius V , the king of Spain and the Venetian Republic, he was asked to command the fleet with everybody’s agreement. But he had to renounce the offer owing to the present danger to his country engendered by local conflicts. [In his place] John of Austria , offspring of emperor Charles V , of great spirit and promising youth, was made commander. Chief Andrea Provana of Leyní joined this expedition with three triremes. It was fought near Nauplia with the support of the Greeks. The Christians had hardly two hundred triremes and the Ottomans more than three hundred. The battle [Mars] was undecided for a long time but finally victory was given to the Christians, with the favor of God or even as a miracle. Provana, who fought bravely in the commanding trireme, was hit by a gun bullet and could hardly escape under the protection of a galley. One of the [Savoy ] triremes, named Margara, was scattered and sunk into the depth; [another one], Pedemontana, was saved many times from the enemy. That victory was celebrated in Turin with thanks given to God and holy days set aside for the people.8

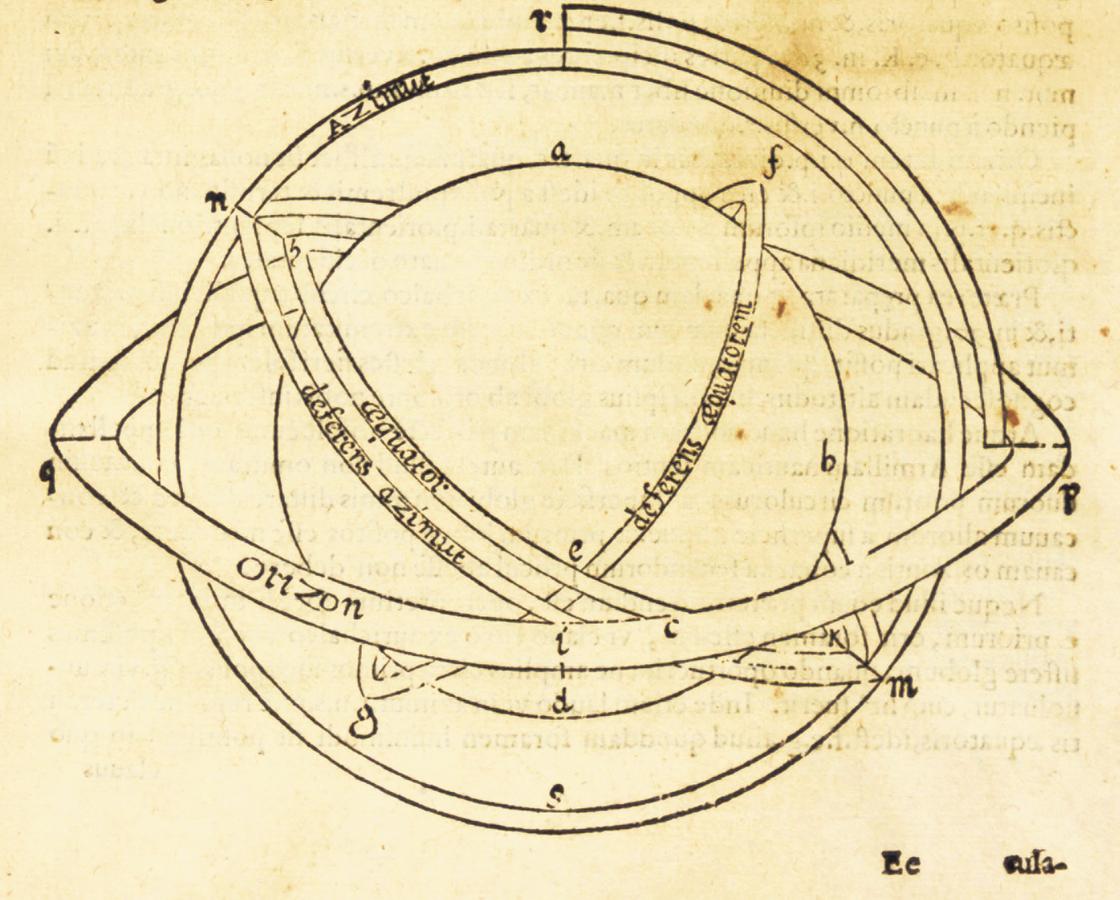

On these occasions Benedetti served as an advisor to Provana

Fig. 2.3: An armillary nautical sphere invented by Benedetti for Andrea Provana for navigation purposes, presumably in the Savoy military expeditions against the Turks. (Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, Library)

2.2 Civil Reforms and Military Policy

Emanuele Filiberto

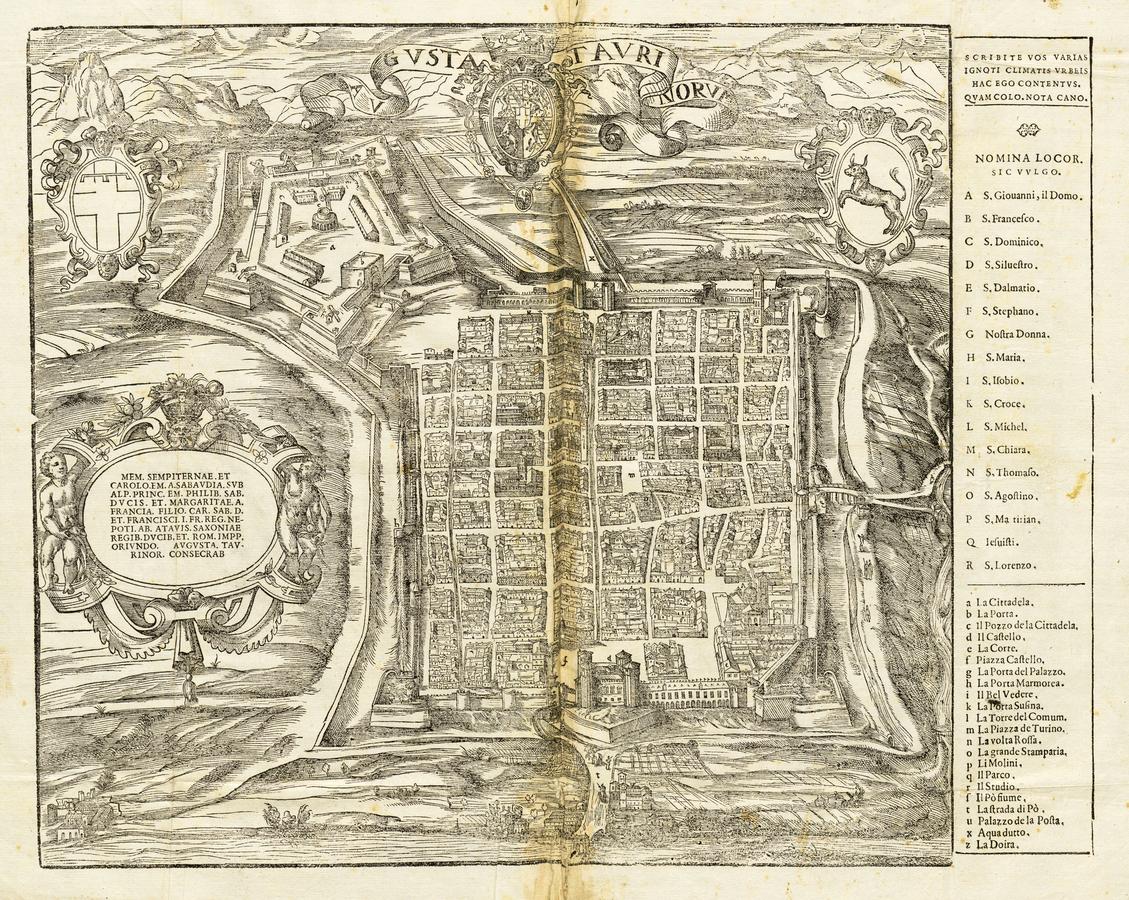

In that year [1564], the duke began building a fortification, which is commonly called the citadel, in the most sacred part of the town on the ruins of the temple of the divine Savior.13

On March 15, 1566, the citadel of Turinwas finished after a few months of work. It was admirable with its five bulwarks, serving all military purposes and built according to the art of architecture. He [the duke] let it be blessed with religious and pious blessings (Archbishop Della Rovere was in charge of the rite). Soon he organized the defenses, entrusting them to Giuseppe Caresana of Vercelli , a subject of his [benemeritus] and a man very expert in the military art.14

Francesco Horologi

As often occurred during the Renaissance, the military-political function of the citadel had two sides. On the one hand, it served to defend the town from possible assaults from outside. On the other, it affirmed the supremacy of the dukes over the new capital and had the function of dissuading the subjects from claiming too much autonomy.15 As Martha Pollak remarked, “Paciotto

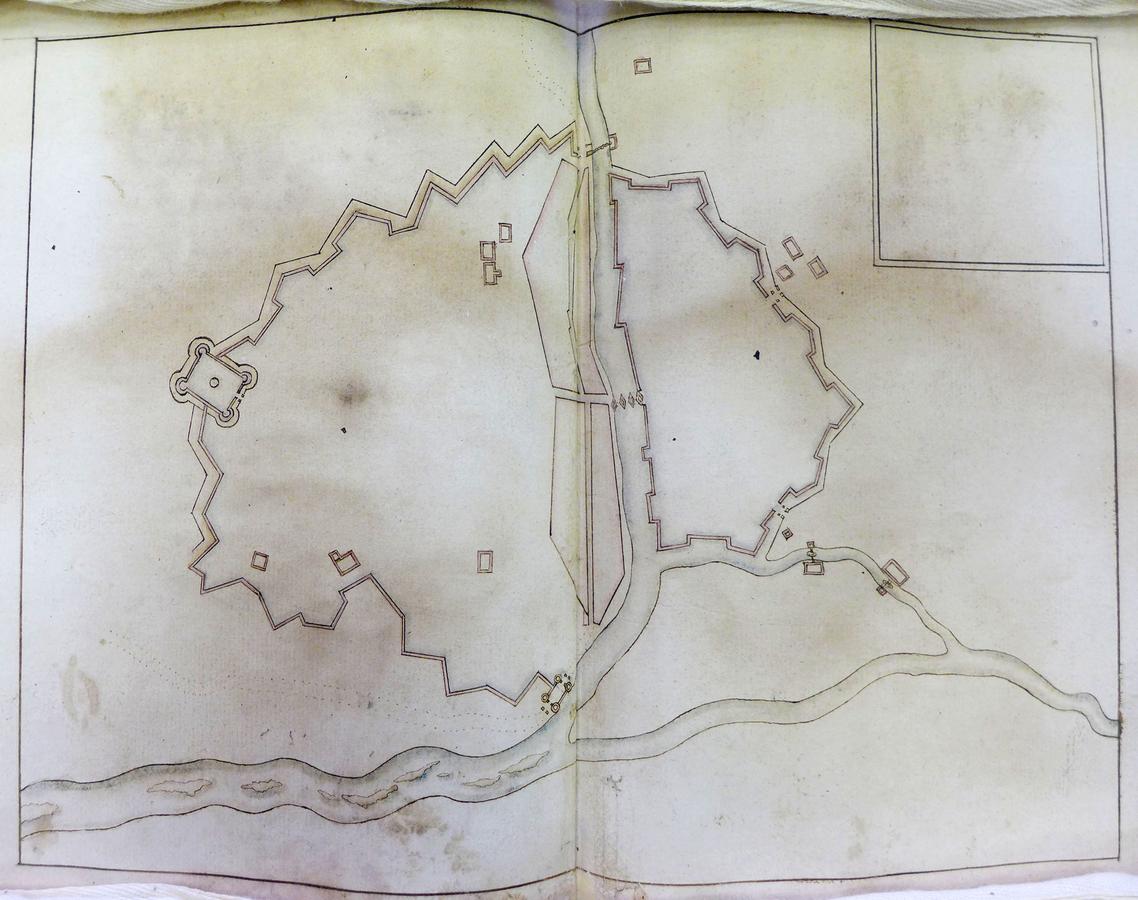

Fig. 2.4: Fortification projects in a drawing by Benedetti’s follower as court mathematician, Bartolomeo Cristini. (Biblioteca Nazionale Universitaria di Torino)

A thorough knowledge of the surrounding territory through cartography, alongside fortification and military reforms, was also seen as an important element of defense. The intensity of mapping efforts in the Savoy

2.3 Engineering and Architecture

Countless engineers worked in Turin

The leading Italian architect of that time, Andrea Palladio

As your Highness is familiar with the most noble arts and sciences related to these issues [concerning architecture], you will have much pleasure and relief by considering the subtle and beautiful inventions of humankind as well as the true science of this art, which you understand very well and which has been brought to the most rare and almost absolute perfection. This is witnessed by the illustrious and royal buildings that have been constructed in many parts of your large and most happy state.23

Urban and military developments were accompanied by a flourishing literature on war and defense theory. Emanuele Filiberto

In this context of military reforms and architectural changes aimed at transforming Turin

Fig. 2.5: Map of Turin in Benedetti’s times, from Pingone’s Augusta Taurinorum (1577). (Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin)

Benedetti interacted with architects and engineers, as can be seen in his correspondence. Four of the scientific letters included in the Diversae speculationes are addressed to the architect Busca

2.4 Intellectual Ferment: Arts, Literature, and Philosophy

Renaissance Turin

Illustrious scholars came to Emanuele Filiberto’s

My Ottonaio

He received the gift of scrutinizing the heavens,

of knowing the reasons for warmth and coldness,

why the days are short or long,

and what layer veils the Sun making it dark,

the manner in which the year becomes adorned of beautiful flowers again,

what nativity is a sign of honor and merit

or of shame and disgrace,

and what is the star presiding over

a man’s state from his birth

until his vital light is extinguished

one circle after the other.33

Giraldi Cinzio

With his gentle and beautiful works

he tries to subtract his name from the oblivion,

defeating the stealing forces of greedy time.

I refer to my gentle Antonio Berga

who shows the way to those who wish to learn

by writing his papers for the common good.34

Two famous authors who visited Turin

As for Bruno

The case of the philosophical poet Pandolfo Sfondrati

2.5 Religious Policy

2.5.1 Pragmatic Counter-Reformation

The relics were moved from the old to the new capital: Christ’s shroud traversed the Alps together with the court. Religion was an essential stabilizing factor. According to the report of the political thinker Giovanni Botero

The other pole of Savoy

The new Inquisition, established in the wake of the Council of Trent

The relations between Emanuele Filiberto

2.5.2 Jesuit Colleges in Piedmont

In 1561 Emanuele Filiberto

In those years, the chair of letters belonged to the Ferrara

The opening of the Turin

Apart from the political interests at stake (the privileges of the town and of the university), the professors’ resistance concerned the contents of the teaching, as one reads in a document from 1593, “Raggioni perché non sia bene che gli Rev[erendi] Padri Gesuiti leggano la filosofia tutta, et la logica nel loro Comento, et si lasci a leggerli nello Studio et pubbliche scuole, come sempre insino a qui si è fatto” (Reasons why it is not good that the Jesuit Reverend Fathers teach all philosophy and logic in their commentary and are allowed to teach at the university and in public schools, as has been the case until now).55 According to the academics, philosophy should be imparted to students as the fundamental tenet of the study of medicine. Therefore, the focus should be set on Aristotle’s

2.5.3 Benedetti and the Counter-Reformation

What can be said about Benedetti’s attitude toward the culture of the Counter-Reformation emerging after the Council of Trent

Among others, he corresponded with Francesco Patrizi

Very Magnificent and Excellent Signore,

I rejoice with your Lordship that you recovered from sickness quicker than believed. And I am very thankful to you for presenting my book to the very serene Prince and promising to inform me about his remarks after he has read it. If by chance the book will be forgotten, due to his many duties [negozii], I hope at least that you will remember me. If his High Serenity will give some sign that he appreciated it [my book], I will be very glad and I will be particularly grateful to your Lordship for your benevolence.56

In exchange, Benedetti sent him a copy of his discussion on the relative sizes of the elements of earth and water, as witnessed by a letter from Patrizi

The two scholars shared views on cosmology that were to be censured by the Inquisition in the 1590s. It is thus expedient to briefly recall Patrizi’s

The censure of Patrizi’s

In Pancosmia, Book 17, f. 103, p. 1, column 2a, he [Patrizi] states ‘that the motion of the Earth is by far in better agreement with reason than the motion of the heavens or the uppermost celestial bodies.’ And he refers to Nicolaus Copernicus’s sentence according to which the sidereal heaven is immobile, along with the stars, while the Earth moves.60

Further theses to be censured were his vitalistic concept of celestial bodies and celestial infinity. The criticism of the latter point goes as follows:

This [to sustain this view] is to dream in very deep obscurity and fall down a precipice after abandoning the common way. In fact, the best and greatest God created everything according to weight, number, and measure. Therefore, everybody agrees that no infinite body is possible in act and no existing multiplicity can be infinite in act. On the empyrean heaven see the Fathers and Thomas Aquinas.61

Patrizi

The Jesuit Benedetto Giustiniani

Not only did Benedetti correspond with intellectuals engaged against the mainstream in Rome

If the souls’ transmigration imagined by the father of Italian wisdom, Pythagoras, were true, I believe that your soul and mine were once the souls of hunting dogs.65

Another indicator of Benedetti’s attitude towards the Counter-Reformation and the confessional quarrels of his time emerges from his approach to the calendar reform. This was a very divisive issue. The pope imposed upon all Christianity an emendation of the calendar in an age when it was affected by profound divisions. In this climate, the pope’s political and religious legitimacy and his authority in such matters was cast into doubt by many, especially in the reformed countries. Reputed Lutheran astronomers such as Michael Maestlin

2.6 Cultural Institutions: University, Academies, Collections, and the Press

The reformation of the Studio was a cornerstone in Emanuele Filiberto’s

Most of the professors (about thirty people) were jurists. Among them, the most reputed was the professor of civil law Guido Panciròli

One of the most reputed professors appointed in Mondovì

Bordiga argued that Benedetti might have taught at the reopened university, first in Mondovì

We could find no direct evidence that Benedetti served as a professor in the documents preserved at the Archivio di Stato di Torino. We considered the acts gathered under the signature “Istruzione Pubblica/ Regia Università di Torino/ Mazzo 1 (1267–1701),” which include the statutes of 1571 and other precious sources concerning the first years of the univeristy. A dossier entitled “1571, Costituzione de’ Riformatori dell’Università dello Studio di Torino, coll’Istruzione da osservarsi da medesimi, colle distribuzioni delle ore per la Lettura, e Rolli de’ Stipendi de’ Lettori” (fascicolo 7 primo) includes decrees concerning the reform of the university, the names of those responsible for accomplishing it, and a list of the chairs with the corresponding salaries and the names of the professors. These documents indicate that the professor of mathematics was Francesco Ottonaio

Turin

His Highness, the very serene [duke] of Savoy, had the wish to found an academy in this august town of Turin . He charged three Jesuit Fathers of the renowned College with the task. Although they are generally sober of mind, in this case they were so intemperate as to entrust myself [with this endeavor] although the overwhelming responsibility [machina da incurvar le spalle] would be excessive for even the most competent person. His Highness has made himself Prince, Protector, and Head [of the academy], in order to attract a good deal of his courtiers [into the academy] who are so cultivated and refined that, if one adds to it the splendor of the arts [lettere], there will be no court in Europe more illustrious than this one. Our name is ‘Incogniti.’77

In spite of the initial impetus, this academy was not particularly successful and did not leave significant traces of its activities. Perhaps it was negatively affected by the fluctuating relations between the Crown and the Jesuit order.

Emanuele Filiberto

In March 1572, duke Emanuele [Filiberto]established in Turin a museum [theatrum] of all disciplines [organized] in marvelous order and at a very high cost. Archbishop Gerolamo della Rovere and the philosopher Ludovic Demoulin de Rochefort , the most educated men in all fields, cared for it.79

Moreover, the dukes supported editorial activities. Emanuele Filiberto

2.7 Scientific Debates

2.7.1 Courtly Conversations

Renaissance Turin

First of all, we should consider courtly debates. A circle of intellectuals gathered around the Savoy

These learned men, played by the Prince like well-tuned musical instruments, immediately give out their specific sounds with words. And they give it their best to be clearly understood in conversations, to please the others with good arguments and to convince them of their opinions. It is like the consonance of truth. In fact, everyone says what one knows or, at least, considers to be true. Hence they discuss natural issues and at times moral ones and mathematical ones. In conclusion, one can regard him [the prince] as Apollo surrounded by the Muses near the water spring that was born from the hoof of Pegasus.81

A reflection of the intellectual climate and the topics addressed in such informal meetings is a poem by the court physician Arma

The day after, Mister Benedetti

And Mister Berga

Expressed opinions that are far from mine:

That the Sun attracts everything to itself with its great brightness

As if it had hands.83

Arma

During the conversation, Ottonaio

On the third day, the prince asked about the origin of lightning, and why we perceive their light before we hear the thunder. Arma

The next issue was colors and the rainbow; Benedetti asked about the center of the rainbow’s arc and Arma

Benedetti, as an expert master of his art,

Asked me about the center of the arc [of the rainbow].

I answered that it was on the vertical line

Descending downward from the center of the heavenly body,

As was the opinion of Zoroaster

And with this answer I got rid of him.84

At the end of this three-day conference, all opinions were written down for the prince and signed by the ducal advisors:

All of this was presented in written form

To His Highness, reporting all speeches.

Dr Berga

Benedetti did the same.

After that we discussed other issues,

Occult things and their effects.85

Other publications also mention such table talks at court. For instance, the physicist and philosopher Bucci

2.7.2 Academic and Scholarly Controversies

Scholarly controversies and polemics on various issues and with very different tones were printed in Benedetti’s years. While courtly debates had a polite and entertaining character, academic disputes could be more vehement. However, the two contexts were not always neatly divided. In 1572 two professors of philosophy, Berga

The court physician Arma

Another polemic opposed Berga

Very serene Prince, the discovery, after two thousand years, that the [element] earth is much more than the [element] water (for which we are greatly indebted to the very learned Mr. Alessandro Piccolomini) very much pleased the spirits of the most renowned philosophers of our time. In the past, they did not dare to depart from the false doctrine they had imbibed for many centuries, although it was sustained by implausible reasons. Today they are glad to embrace the opposite opinion [concerning water and earth], because both the senses and reason are in accordance with the [new] demonstration of the truth. The ancient mistake has been unveiled by the mathematical school with very certain proofs that offer a firm foundation of the measurement of the heavens and the Earth.92

The dispute continued with the Latin translation of Berga’s

2.7.3 Astronomical-Astrological Polemics

In Renaissance Turin

I cannot stop wondering who this person is. I cannot understand why he sometimes presents himself as a scholar, sometimes as a cook, as a Romancourtier, or as a practicing friar [frate osservantino] (as he speaks about the osservantini). I cannot believe that he is a practicing [man of religion], as the ecclesiastics speak in a correct manner and not heedlessly like him (who behaved heedlessly). Moderation has always been praised. Therefore, moderate people will always damn this person. I will never believe that he is a scholar. In fact, today’s scholars are well-educated and would never indulge in such excesses, especially against such a man [Dr. Arma ] from whom they did not receive anything but pleasure, honor, and courtesy. Although he seems to come from the area of Rome, in the end he shows himself to be a dishwasher because even a cook would behave better than him. Whoever the hell he is, if he will not control himself better in the future, I will repay him as he deserves.97

Possibly the identity of this mysterious denigrator was the philosopher Giordano Bruno

Only one year later, between 1580 and 1581, Benedetti was involved in an astronomical-astrological quarrel with a certain Benedetto Altavilla

2.7.4 Posthumous Criticism: Cristini

Benedetti died on January 20, 1590, two years before his own astrological prediction. This untimely death did not leave him the time to complete the astrological work that he announced at the end of the Diversae speculationes. What is worse, the fact that his own prediction was wrong awakened doubts and rumours about his scientific talent. The mathematician Cristini

Cristini

Benedetti published his prognostication of the moment of his death in the work entitled Diversarum speculationum mathematicarum et physicarum liber (published in 1585), in a letter to the most illustrious Wolfhard Eisenstein[Volfardus Aisenstain], which is to be found at the end of this work. After a brief assessment of those things of the judicial art that he regarded as vain or false, and after announcing to Wolfhard that he would expand [on astrology] in that tract with his astrological observations, which he wished he could publish before his death, he added the indication of the time in which, according to him, [his death] was to happen (that is, [the date] before which he wished he could publish the aforementioned tract). These are his words: “antequam ad directionem mei horoscopi cum corpore Martis anaeretae perveniam, quae quidem directio circa annum millesimum quingentesimum nonagesimum secundum evenienti” [as indicated by my horoscope, before I meet the body of the adverse Mars. This is going to happen in 1592].

As we can see, he was certain that he would die when the direction of his ascendant and Mars would meet. He calls [Mars] “anaereta,” that is, giver or announcer of his death. He confirmed this when […], just before his death, he felt that the disease was attacking him and declared that he made a mistake of four minutes in the rectification of the time of his birth horoscope [natività]. This is as if he would say that, by augmenting by four minutes the time of his birth horoscope, he would have predicted the direction [of his ascendant sign meeting Mars] at about the time when he became sick. Hence, he believed he was dying, and this [his death] in fact occurred at the end of the ongoing year 1590, at 17:00 of 20th January according to [the calendar of] Gregory, which corresponds to the 10th of the old [calendar]. I had to know the time in which he believed he was born in order to assess by how much time he was mistaken in the rectification of his birth horoscope, so that the direction of his horoscope relative to Mars corresponded to the days when he left this world. Therefore, at Benedetti’s death, I immediately began to compute the error of the aforementioned time, though only approximately, because I did not know Mars’s latitude. And I found that it [the mistake] amounted to eight minutes […]. Later, when the same person who told me that Benedetti had acknowledged a mistake of only four minutes according to his calculations, openly accused me of not being able to do this calculation, as my mistake was two times [that of Benedetti], I began the calculation in the following manner. First, I determined the time attributed to his birth […] Etc.104

In his transcription of Cristini’s

But your very generous Highness awoke in my spirit the desire of mathematical virtues and of undertaking the present endeavor. Your request woke up and unveiled in me the desire (which is always alive) to serve [Your Highness]. However, my desire has been impeded by the difficulties of my continuous poverty and adverse times owing to the fact that no treasurer (or any monetary and financial administrator) regards me as an ordinary servant of Your Highness. [I have been acknowledged as a servant] only in exceptional cases, when my capacity, readiness and knowledge in making calculations has proved useful—as has happened several times, when I was required to serve Your Highness. […]

Therefore, I place growing hope only in Your Highness the more [you] require my services, the more efforts I make for You and the fewer are the number of [benefactors] by whom I can hopefully be supported105

In this case, the allegation against Benedetti is for using the Alfonsine

I took into account the places where they [the planets] are to be found in the horoscope made according to the true time calculated on the basis of Copernicus, following the teaching of the major authors on astrology. In general, since scholars are in disagreement concerning the employment of different tables to compute their horoscopes [revolutioni] and although I have demonstrated (in the calculations at the beginning of my tract) that only one set [of tables] is true, I calculated the astrological figures of the heavens according to both tables—in fact, false ones were also in use by many and in particular by Benedetti—and I offered double astrological judgments depending on the places assigned according to the different figures. In this manner, your Highness will possibly compare them and see which ones are in better agreement with the truth.106

The terms of Cristini’s

But I believe that he [Benedetti] followed the calculation of Alfonso Xrather than the true one only owing to its simplicity. In fact, before [the publication of] the ephemerides of Magini it was very difficult to establish the true time of the revolution. Before him, nobody calculated the Sun up to the seconds in any ephemerides, which is the presupposition for more exact and true computations […]. It is only in consideration of Benedetti’s authority that I did not omit to compare his horoscope with the other one.109

In this second criticism, Cristini

Once he had established himself as an expert in the field, Cristini

2.8 Strengths and Limitations of the Institutional Framework of Benedetti’s Science

Benedetti’s life, career, and work, as well as his legacy, fortunes, and misfortunes should be understood against the background of the Renaissance world he was part of, in particular the Italian and Turin

Given this context, Benedetti’s scientific activity, accomplished outside university and institutionalized settings, cannot but appear as occasional. In fact, it was linked to the contingency of courtly life, for instance to the requests for advice by the Savoy

One astonishing aspect of Benedetti’s intellectual activities is the lack of an enduring and explicit legacy. On the one hand, his conceptions clearly influenced contemporaries and followers in Italy and abroad. Among others, his impact is reflected in the positive opinions of Brahe

In many ways, Benedetti is the mirror of his world, in particular of the courtly society he belonged to. His work can be seen as the embodiment of this context. His case is different from that of many other Renaissance scholars, who strongly identified themselves with their scientific work and output. For scholars like Galileo

Footnotes

Benedetti 1585, f. A2r: “Agitur nonus decimus annus ex quo litteris Serenissimi patris tuae Celsitudinis, accersitus ex urbe Parmensi in hanc me civitatem contuli. Is advenientem tam humane excepit, tanta deinde liberalitate fuit complexus ego vicissim ei deserviendi, tam vehementi cupiditate fui accensus, ut sub eius ditione quod superesset vitae agere constituerem.”

Benedetti 1585, f. A2r: “Cuius in me banignitas, mea in illum observantia mirum in modum mutuo usu, et consuetudine est adaucta, ut idem Dux me secum dum rusticaretur esse vellet, saepe etiam secum pernoctare; quo quidem tempore de Mathematicis scientiis mecum agebat, in quibus perdiscendis mea opera utebatur, quaestiones, Arithmeticam, Geometriam, Opticen, Musicam, aut Astrologiam spectantes proponens.”

Firpo 1983, 123: “Non è quel duca litterato, ma ama li virtuosi, et però ne tiene alquanti appresso di sé, sente piacere a udirli ragionare, egli stesso li fa de quesiti, ma nessun ragionamento più li diletta, che quello delle matematiche, come scientia, che non solo è conveniente ma ancora è necessaria alla professione del capitano.”

Firpo 1983, 211: “Ha il signor duca di Savoja un bellissimo ingegno capace d’ogni scienza: ma non ha atteso alle lettere con quella diligenza, che si converria a chi ne volesse sapere, essendo la sua principal professione il mestiero della guerra […]. E perché la scienza delle matematiche è molto utile e necessaria a chi vuole fare questa professione de l’arme, però se ne diletta assai Sua Eccellenza [Emanuele Filiberto] e di quella sa assai più che mediocremente. Con tutto questo sapendo che l’uomo tanto sa di ogni scienza quanto continua in vederla e studiarla, però usa di udire ogni giorno una lezione o d’Euclide o d’altro scrittore di quelle scienze da un messer Giovan Battista Benedetti veneto; uomo, per opinione non solamente mia, ma di molti valentuomini ancora, il maggiore che oggi faccia professione, e di grandissimo gusto del Signor Duca; perché oltre a possedere lui quella scienza eccellentissima sa anco così bene insegnarla ad altri che con molta facilità ne fa restar capacissimo chi lo ascolta.”

Pingone 1577, 85: “Anno Christi 1565 mense Iunio, Dux Emanuel, obsessa a Turcis Melita, Andream Provanam Leniacum cum triremibus quatuor instructissimis mittit, qui una cum Pontificiis, Hispanis et aliis triremibus suppetias insulae afferret. Prior Leniacus applicuit, difficultates exploravit, alios postea advexit, et soluta tandem faventibus superis obsidione, Hierosolymitanorum militum sacer, et strenuus ordo liberatus, Ioanne Valleta Gallo summum magisterium gubernante. Quam ob victoriam Taurini immensae laetitiae publica significatio reddita, et devotae superis gratiarum actiones.”

Pingone 1577, 88: “Anno Christi 1571 Emanuel Dux Taurini agens, confoederatione inita in Turcam Cypri vastatorem, inter Pium quintum Pontificem, Hispaniarum Regem, et Venetam Rempublicam, qui classi praeesset ab omnibus exposcitur: sed ob imminentiam a vicinis discordiis patriae discriminis, excusatus habetur. Ioannes vero Austriacus Caroli quinti Caesaris soboles, magni animi, et expectationis iuvenis praeficitur. At Dux Andream Provanam Leniacum tribus cum triremibus in eam expeditionem adiungit. Apud Naupactum Achaicum concursum, et decertatum. Christianorum vix ducentum triremes: Turcarum vero plusquam trecentum: Mars diu anceps, tandem Deo maximo favente, et quodam potius miraculo ad Christianos inclinavit victoria. Leniacus ex triremi Praetoriam fortiter dimicans sclopeto ictus in capite vix galeae praesidio evasit: triremium una Margaris nomine dissipata, mersaque penitus, Pedemontana semel atque iterum ab hostibus recepta. Ob eam victoriam, Taurini supplicationes superis, feriae mortalibus indictae..” See also Tonso 1596, 142, 161 and 177–179.

See Stumpo 1993, 561.

Pingone 1577, 85: “Eo anno [1564] Dux in aeditiore parte civitatis, in ipsis templi Divi Solutoris ruinis Acropolis aedificare coepit, Cittadellam vulgo dicunt.”

Pingone 1577, 86: “Anno Christi 1566 idibus Martiis, absoluta paucis mensibus Taurinensi acropoli, quinis propugnaculis admiranda, servata omni rei militaris, et architectonicae artis ratione eam religiosa ac pia benedictione communiri curat, Archiepiscopo Rovereo sacris praeeunte: mox praesidiis firmat, eique praeficit Iosephum Caresanam Vercellensem de se benemeritum, ac rei militaris peritissimum.”

The Archivio di Stato preserves Carracha’s maps of Turin: Augusta Taurinorum (1577) and Turino (ca. 1580)—see Archivio Storico della Città di Torino 1982.

Palladio 1570, III, 5: “Ne’ quali [edificii publichi], perché di maggior grandezza si fanno, e con più rari ornamenti, che i privati, e servono a uso, e commodo di ciascun; hanno i Principi molto ampio campo di far conoscere al mondo la grandezza dell’animo loro; e gli Architetti bellissima occasione di dimostrar quanto essi vagliano nelle belle, et meravigliose invenzioni.”

Palladio 1570, III, 3: “Principe, il qual solo a tempi nostri con la Prudenza, e co’l valore s’assimiglia a quelli antichi Romani Heroi, le virtuosissime operationi de’ quali si leggono con maraviglia nell’historie, et parte si veggono nell’antiche ruine.”

Palladio 1570, III, 3: “Delle qual cose [concernenti l’architettura] essendo l’A[ltezza] V[ostra] dotata delle più nobili arti, e scientie; piglierà non poca contentezza, e consolazione considerando le sottili, e belle invenzioni degli huomini, e la vera scienza di quest’arte, da lei molto bene intesa, e ridotta a rara, e perfetta perfezione; come dimostrano gli illustri, e reali edifici fatti fare, e che tuttavia si fanno in diversi luoghi dell’amplissimo, e felicissimo suo stato.”

The letter is to be found in Benedetti 1585, 330–331. The collocation of the volume in the Biblioteca Reale di Torino is G 43 8.

“Move insieme con lor verso te il piede il mio Ottonaio, a cui scorrere il cielo, per grazia, diede. Del caldo la cagion saper, del gelo, e perché breve sia, sia lungo il giorno, e quale offoschi il sole oscuro il velo; come ritorni di bei fiori adorno l’anno e chi debba aver dal nascimento onore e pregio, e qual ingiuria e scorno; e da che stella prender de’ argomento de lo stato suo l’uom, poi ch’egli è nato, insin che il suo vital lume sia spento di cerchi in cerchio.”

“E quel che, con gentil opre, e leggiadre, tenta che il nome suo da l’oblio s’erga, vinte del tempo avar le forze ladre, i’ dico il mio gentile Antonio Berga, che addita, a chi imparar cerca, la strada, mentre, ad util comun, le carte verga.”

Firpo 1993, 159. See Ricci 2000.

See Griseri 1998.

In a letter to Benedetti, Francesco Patrizi asked him to give his regards to Baron Sfondrati. See Patrizi 1975, 42–43.

See Omodeo 2008b and Omodeo 2012a.

“La gente infervorata di devotione è molto più regolata: e per consequenza più ubidiente al Suo Prencipe, che la dissoluta.” Botero 1608, 241.

For instance, Giraldi Cinzio defended the famous commentator on Aristotle’s Poetics, Ludovico Castelvetro, who was excommunicated in 1560 as “eretico fuggitivo e impenitente” for his alleged bias towards Melanchthon. On this occasion Giraldi Cinzio argued that violence and coercion could only produce the opposite effects than those wished for by the defenders of orthodoxy. See Cinzio 1996, Letter n. 101, 371, n. 3.

Cinzio 1996, Letter n.127, 425: “Sed Taurino iam menses quatuor absum, Ticinique publice profiteor. Nam, praeter iacturam valetudinis, quam ibi quotidie faciebam, me ad abeundum urgentem, natio illa haec nostra studia nihil quidem facit. Hinc Princeps ille, qui oratoriam ac poeticam facultatem profiteretur, in Academia sua habere constituit neminem, quod satis esse censuerit Iesuitas nescio quos, suo in collegio, hoc muneris cum puerilis ac infantibus obire; qui, cum Deuspaterio quodam, barbaro plane auctore, mollia ingenia, obscurissima, ne dicam foedissima, imbuunt barbarie. Me tamen abeuntem, praeter annuam quadrigentorum aureorum nummum stipe, quam liberaliter exsolvit, centum etiam scutatis aureis donavit.”

Patrizi to Benedetti (Ferrara, 21 March 1583), Patrizi 1975, 39.

Archivio di Stato di Torino, Istruzione Pubblica/ Regia Università di Torino/ Mazzo 1 (1267–1701), Fascicolo 7/2. The document is included as an appendix to Omodeo 2014d.

Patrizi 1975, XXVII, 53: “Molto Magnifico et Eccellentissimo Signore, mi rallegro con Vostra Signoria, che più tosto che non credea si è rilevata dal male, e li rendo moltissime gratie dell’haver presentato il mio libro a quel Serenissimo Prencipe, e ricevuto il favore, che Ella mi avvisi ciò che haverà detto, dopo che l’havrà letto. Et se per sorte per li molti negozii il libro andasse in oblio, spero da Lei il rimedio di un poco di ricordanza, la quale, se partorirà alcun segno che Sua Altezza Serenissima l’habbia havuto caro, mi sarà carissimo e tutto l’obbligo l’haverò a Vostra Signoria e all’amor suo verso me.”

Patrizi 1975, 57–58. In the letter Ottonaio is also mentioned as a common acquaintance and an intellectual partner.

Baldini and Spruit 2009, Vol. I, 3, 51, doc. 1, 2216: “Lib. 17 Pancosmias fol. 103, pag. 1, col. 2.a ait quod Terram revolvi longe videtur esse rationi consonantius, quam Coelum, vel suprema astra moveri. Et refert sententiam Nicolai Copernici dicentis Coelum sydereum stare simul cum stellis, Terram vero moveri.”

Baldini and Spruit 2009, Vol. I, 3, 51, doc. 1, 2219: “Hoc est somniare per altissimas tenebras, et a via communi declinando in praecipitia ruere, nam cum Deus opt. Max. omnia in pondere, numero, et mensura produxerit, nullum infinitum corpus actu dari nullamque rerum subsistentium multitudinem actu infinitam omnes viri fatentur. De Coelo empyreo consultat Patres, et sanctum Thomam.”

For a reconstruction of the anti-Platonic reaction also affecting the reception of Patrizi, see Rotondò 1982. On the censure of 1616, see Bucciantini 1995, Bucciantini, Camerota, and Giudice 2011 and Omodeo 2014a, chap. 7.

Benedetti 1585, 285: “Si vera esset animorum illa transmigratio quam sibi Italicae sapientiae Pater Pythagoras effinxerat; tuam, meamque existimarem animam canis, quandoque venatici fuisse.”

On Argenterio, see Temkin 1974, 141–144 and 149–152 and Mammola 2012, 185–193.

On the philosophical culture of Turin of those years, in particular on Bucci, see Mammola 2013.

See Gilbert 1965.

Tonso 1596, 141: “Neque vero liberalium disciplinarum omniumque artium colendarum quam susceperat cogitationem unquam deposuit: nam et publicum earum Gymnasium pro tempore in oppido Monteregali instituit: et qui viri in quacunque scientia excellerent undique conquisuit. […] Mathematicos illustres Franciscum Othonarium, et Io. Baptistam Benedictum Venetum.”

Bordiga derived this information from a manuscript of Cristini’s preserved in the Biblioteca Marciana in Venice. See Bordiga 1926, 596–597.

The historian of Piedmontese Universities Silvio Pivano complained already in the 1920s about the lack of relevant documents. Pivano 1928, 19–22.

See, e.g., Bauer 1991, 156–157.

Roero 1997, 65, n. 5. Evidence for Benedetti’s role as an advisor in university matters can be found in Patrizi’s correspondence, as already mentioned.

Tiraboschi 1824, 289–290: “L’Altezza di questo Serenissimo di Savoia ha desiderato, che si dia principio a fondar un’Accademia in questa sua Augusta cittá di Turino, et n’ha data la cura a tre Padri del Gesù di questo insigne Collegio, i quali, non so da che allucinati, soliti però a non s’abbagliare, hanno fatto gran fondamento nella persona mia, caricandomi d’una macchina da incurvar le spalle, quantunque gigantesche. S.A. se n’è fatto Principe, e Protettore, e Capo, per tirarvi buon numero de’ suoi Cortigiani, tanto culti e fioriti nel resto, che, se vi si aggiugne l’ornamento delle belle e delle pulite lettere, non sarà Corte in Europa più rilucente di questa. Il nostro nome è degli Incogniti […].”

Mamino 1992 and Mamino 1995. By contrast, Cibrario thought that it was an encyclopedic project. See (Cibrario 1839).

Pingone 1577, 88: “Anno Christi 1572 mense Martio, Emanuel Dux Taurini theatrum omnium disciplinarum miro ordine, nec minimis sumptibus instituit, curantibus Hieronymo Ruvereo Archibiscopo, et Ludovico Molineo Rochefortio Philosopho, viris in omni doctrinae genere absolutissimis.”

On Renaissance publications in Piedmont, see Bersano Begey 1961, especially vol. 1. See also Merlotti 1998.

Trotto 1625, 2–3: “[…] questi huomini saputi, tocchi dal Prencipe, come instrumenti musici bene accordati, subito rendono ciascuno il suo suono con le parole et quanto meglio possono procurare d’essere intesi discorrendo, e di dar diletto con le buone ragioni, et anco di tirare gli altri al suo parere, come ad una consonanza della verità: perché ognuno dice quello ch’egli sa o crede almeno sia vero. E quindi si veggono trattare hor cose naturali, hor morali, hor mathematiche. Sì che egli quasi come uno Apolline si può dire, che sta fra le Muse, intorno al fonte, che uscì dal colpo del piede del cavallo alato.” On Trotto’s teaching, see Vallauri 1846, 28 and 48–49.

Arma 1580a, f. A2r: “Scalda co raggi […]/ Sbattendo la Terra di caldo priva. Sì com’il martel che bate l’incudine,/ Riscalda l’un e l’altr’in certitudine.”

“Il Signor Benedetti l’indomani Col signor Berga, insiem’ a l’Ottonaglio Forn’in pensier’ a me d’assai lontani, Che’l Sol tirass’a sé com grand’abbagio Ogni cosa si com’havesse mani.”

“Il Benedetti, come degno maestro, Mi dimandò d’il centro di tal arco. Dissi, che gliera col centro de l’Astro, Ne la medema linea giù scarco. Si com’anchora volse Zoroastro. E con tal dire di lui mi discarco.”

“E tutto quest’in scritti fu donato A Sua Altezza, con tutti soi detti. E fu dal Dottor Berga conformato. Il che fece’l signore Benedetti. Fu poi d’altre proposte ragionato E de gl’occolte cose, e soi effetti.”

Bucci 1572 and Berga 1573.

See Mammola 2013.

Merlotti 1998, 585: “Come s’è visto per la polemica fra Costeo e Arma […] non si trattava di isolati testi a stampa che generavano dibattiti destinati a rimanere manoscritti e chiusi nell’ambito degli eruditi, ma semmai del contrario: di discussioni, cioè, sorte in circoli ristretti di medici e scienziati, prima affidate a manoscritti e poi trasportate a stampa a vantaggio d’un più vasto pubblico.”

For an accurate reconstruction of the polemic and its cultural and scientific context, see Ventrice 1989, 103–145 and Mammola 2014.

Benedetti 1579, 3: “[…] l’essersi doppò due mila e più anni scoperto con trionfo della verità, che la terra è molto maggiore dell’acqua, (del che si ha da haver grande obligo tra gl’altri al dottissimo Signor Alessandro Piccolomini) ha non poco rasserenato, Serenissimo Principe, l’animo de’ più famosi Filosofi di nostra età; i quali, sì come prima non intendeano dipartirsi dalla già imbevuta falsità, e per molti secoli adietro, benché con inefficaci ragioni difesa, così hora si lasciano volentieri persuadere il contrario; poiché il senso, e la ragione s’accorda alla dimostratione del vero. E nella scuola de Mathematici per certissime prove si scuopre l’antico errore, puotendosi far fondamento stabile delle misure de cieli, e della terra.”

Arma 1580b: “Il Creator gli diede tal misura./ Che saper non si può da creatura.”

This information stems from Bonino 1824–1825.

It is preserved in the Biblioteca Reale of Turin, coll. G 25–67.

Della Torre 1578: “[…] non mi posso quietare pensando chi possi esser costui. Non posso capire, perché quando fa d’il scuolaro, quando del cuogo, quando del corteggiano di Roma, quando del frate osservantino, poi che di osservantini parla. Di esser osservante, nol posso pensare, perché li religiosi parlano correttamente, e non si sgovernano nel parlare, come ha fatto costui, il quale mattamente si è sgovernato. Fu sempre lodata la modestia. Sarà donque dalli modesti dannato costui. Che sij scuolaro, non lo crederò mai, perché hoggi dì li scuolari sono ben creati e non farebbono tale scappate specialmente contra di un’huomo tale da cui mai hebbero altro che apiacere, honor e cortesia. Par bene che habbi del Romanesco nel principio, ma il fine dimostra più presto haver del sguattero, perché il cuogo si sarebbe meglio deportato che non fa costui. Sij chi diavol esser si voglia. Se esso per avanti meglio non si governarà, tale e tanto mi ritrovarà, quale e quanto mi ricercarà.”

See Omodeo 2008a. On Bruno’s lost meteorological-cometary work, see Ernst 1992.

On astronomical-astrological quarrels in Renaissance Italy and Turin, see Omodeo 2008a and Tessicini 2013.

Vernazza 1783. Two manuscript copies of Vernazza’s biography of Cristini are still extant. One is preserved in the Turin State Archive (Archivio di Stato di Torino, coll. Miscellanea J.b.VIII. 9), the other is kept in the Biblioteca Reale of Turin (Vernazza manuscript, misc. 67.5). The latter is a good copy, ready for the printer. It contains an appendix of “documents” for the personal use of the author. These are transcriptions or translations of significant passages of documents by Cristini that were lost or seriously damaged after the fire at the Turin National Library in 1904. They comprise the dedication and table of contents of the Revolutione trentesimaterza del Ser[enissi]mo Sig[nor] il Signor Carlo Emanuele duca di Savoia (1596), notes from various astrological diaries, an Italian version of the beginning of La rithmomachia o sia gioco di Pithagora and, most importantly, a long extract from the Essaminatione dell’errore… della natività del fu S[ignor] Gio[vanni] Battista Benedetti mathematico.

From Vernazza’s papers accompanying his manuscript of his Notizie di Bartolommeo Cristini. Biblioteca reale di Torino, Misc. 67.5, Vita di Bartolomeo Cristini con documenti, “M.S. L.1.10, 11.493, di pag. 42.” See Omodeo 2014b: “Ha pubblicato il Benedetti, il pronostico fattosi del tempo di sua morte nell’opera sua titulata Diversarum speculationum mathematicarum et physicarum liber stampata dell’anno ’85 in una lettera scritta all’ill.mo Volfardo Aisestain, posta nel fine d’ess’opera, percioché appresso haver brevemente dichiarato quali cose egli stimava vere nella giudiciaria e quali vane o false, et detto com’esso Volfardo potrà veder poi meglio in quel trattato dell’osservationi sue astrologiche, quale sperava dar in luce avanti la sua morte, soggiunge il tempo il quale giudicava essa doverli avvenire, o sia avanti al quale desiava pubblicar detto trattato, con queste istesse parole: “antequam ad directionem mei horoscopi cum corpore Martis anaeretae perveniam, quae quidem directio circa annum millesimum quingentesimum nonagesimum secundum evenienti.” Donde appare ch’esso teniva per certo d’haver a morire, quando giongerebbe alla direttione del suo ascendente al corpo di Marte, quale chiama anaereta cioè datore, o promissore de la morte sua. Il che pare habbi volsuto confirmare quando che, come dice, poco avanti la sua morte ei si sentì carrigar dal male, disse d’essersi fallato di quattro minute nel rettificare il tempo di sua natività, perché questo è come s’havesse detto che quando egli havesse accresciuto tempo di sua natività per quattro minute havrebbe conosciuto la direttione predetta essere minore di quello [che] l’haveva fatta, et periciò il tempo della sua morte caggionata da essa direttione dover essere circa questo tempo, ch’egli s’era infermato, et credeva di morire come è pur avvenuto, essendosi occorso ciò fare dell’anno presente 1590 circa le 17 hore del 20 giorno di genaro secondo Gregorio, che viene ad essere il dieci dell’anno antico. Perciò volendo io essaminare di quanto tempo egli habbi fallato nella rettificatione di essa sua natività, accioché giustamente la direttione predetta dell’horoscopo suo al corpo di Marte venisse a cadere nel giorno istessi ch’egli partì da questo secolo, m’è stato necessario sapere il tempo ch’egli havea presupposto fosse quando nacque […]. Perciò mi posi subito seguita la morte del Benedetti a far conto dell’errore del tempo predetto, così alquanto alla grossa, per non haver nota la sopradetta latitudine di Marte, et ritrovai detto errore essere di minute otto in circa di hora […] Ma perché ho dipoi inteso che chi mi ha riferto il Benedetti haver confessato il detto fallo di min. 4 et haver solamente ritrovato tanto per calculo ha espressamente detto che io errava del doppio et non sapea far questo conto […] mi posi a calculare di questa maniera. Prima ho ritrovato il tempo presupposto della natività […] Etc.”

Cristini, Revolutione, Biblioteca Nazionale Universitaria di Torino, N. VII. 10, f. 4r–v: “Ma V[ostra] Alt[ezza] benignissima sì come è stata cagione d’eccitar nell’animo mio il desio delle vertù matematiche, et di farmi fare la presente fatica; così ancora co’l chiamarmela adesso ha risvegliato, o riscoperto le sempre vive brame mie di servirla, le quali erano tenute sepolte dai disaggi che queste carestie et mali tempi mi causano maggiori giornalmente, percioché non sono conosciuto per servitore ordinario di V[ostra] Alt[ezza] da Tesoriere alcuno, né da ministro di suoi dinari o finanze; se non ne’ casi che la vertù et prontezza, o cognizione mia ne’ conti, può reccarli qualche giovamento come ha fatto più volte quando per servitio di V[ostra] Alt[ezza] sono stato da loro richiesto […].

Et per questo sempre cresce maggiore la speranza mia, in solo vostra Altezza quanto ch’essa più m’incita a servirla, et che maggior è fatica che faccio per lei, et minor il numero di quelli in quali posso haver spernaza di soccorso.”

Cristini, Revolutione, Biblioteca Nazionale Universitaria di Torino, N. VII. 10, f. 8r: “[Ho] havuto riguardo ancora ai luoghi ne’ quali cadono essi [pianeti] nella figura della revolutione fatta secondo il vero tempo dato dal Copernico, come è insegnato da principalissimi scrittori dell’astrologia. Et nell’universal giudicio perché ho conosciuto tra scrittori essere certa diversità seguendo alcuni un tempo et altri un altro nel fare delle revolutioni delli quali ancor ch’io provi (come per i calculi di ciascuno posti al principio di questa opera) l’uno solo essere il vero, ho fatto le figure del cielo che si mostrano sotto ambi essi tempi (atteso che ancor la falsa era seguita da diversi et particolarmente dal Benedetti), ho radopiato essi giudici per i luoghi che diversi significati fanno havere esse figure. Accioché V[ostra] Alt[ezza] provandole ambidue conosca ancor lei quale meglio secondi la verità.”

Cristini, Revolutione, Biblioteca Nazionale Universitaria di Torino, N. VII. 10, ff. 11v–12r.

Cristini, Revolutione, Biblioteca Nazionale Universitaria di Torino, N. VII. 10, ff. 12v–13r.

Cristini, Revolutione, Biblioteca Nazionale Universitaria di Torino, N. VII. 10, f. 16v–17r: “Ma io tengo ch’egli seguisse più tosto il calculo d’Alfonso che il vero; solo per causa della facilità d’esso percioché avanti l’effemeridi del Magini molto difficil cosa era trovar il tempo vero della revolutione percioché nissuno avanti lui havea nell’effemeridi calculato il Sole sino alle seconde onde ne seguono i calculi più sottili e veri […]. Con tutto ciò solo per l’autorità d’esso Benedetti non ho volsuto lasciar del tutto la consideration delle figura sua con l’altra come vedevasi.”

See Peyron 1904, 617–618.