1.1 The Life and Career of a Renaissance Man

Giovanni Battista de Benedetti came from a patrician family of Venice

We make, create, and constitute the aforementioned Giovanni Battista Benedetti as a true noble of the Holy Roman Empire and of our Empire forever, alongside all his legitimate and natural sons and daughters (those who are already born and those that will be born). We will call and fully declare them such [nobles of the Holy Roman Empire]—although he and his predecessors are noble and were born from an ancient and noble progeny, as we are very well informed.1

In those years, the establishment of the Savoy

On the occasion of the conferral of the patent on Benedetti, the cross of Savoy

During the Renaissance, nobility was more important than professional appurtenances or academic titles. For instance, the celebrated Danish

The small star of Cassiopeia would not shine as brightly as this nova over the whole surface of the Earth because of the dry fumes placed in-between, if they had been only under that one, and did not affect in the same manner the other stars next to it and augmented that unusual light. But the most excellent philosopher GIOVANNI BATTISTA BENEDETTI, THE VENETIANPATRICIAN, eminently and skillfully demonstrated this with geometric arguments, in [his] outstanding work concerning mathematical and physical speculations (around the end of his letters). Writing to Annibale Raimondo […] he clearly showed the absurdity which necessarily follows from his false assumption [i.e., the sublunary position of the nova].6

Fig. 1.1: An example of the titles Benedetti added to his name in his publications. In the title page of De gnomonum umbrarumque solarium usu (1574), he called himself “Venetian Patrician, Philosopher.” (Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, Library)

The prominence accorded to lineage is evident from Brahe’s

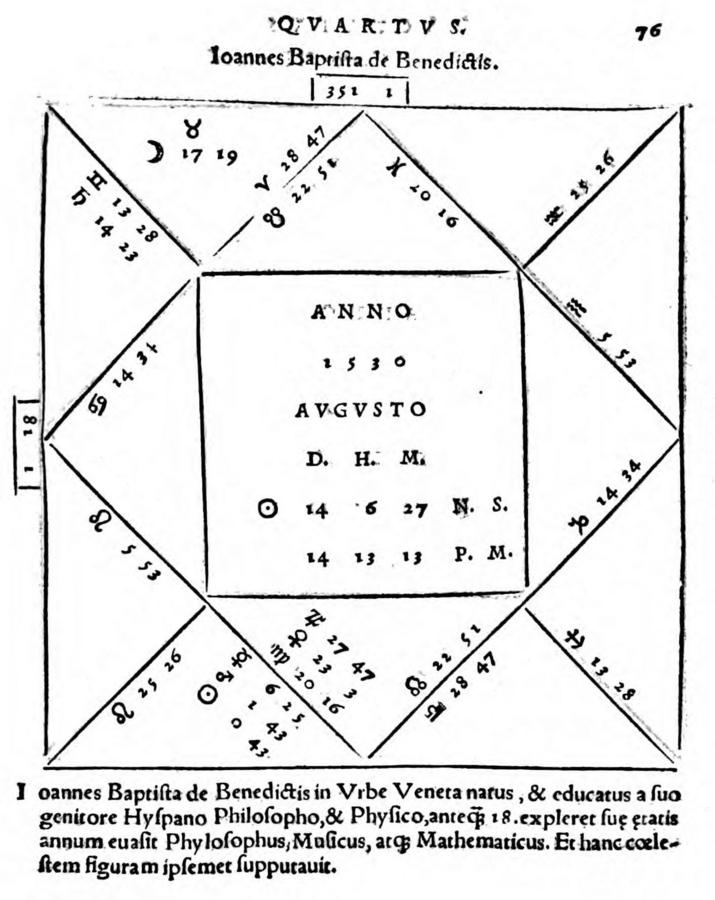

Apart from his nobility, we do not know much about Benedetti’s origins. According to a horoscope that he cast for himself (Figure 1.2), and was printed by the Neapolitan

Fig. 1.2: Benedetti’s own horoscope, in Luca Gaurico, Tractatus astrologicus (1552), f. 76r. (Bayerische Staatsbibliothek)

For the greater part of his life Benedetti was a courtier. For several years he served duke Ottavio

Fig. 1.3: A modern sundial on the Church of San Lorenzo in Turin reminiscent of those designed by Benedetti. (Own photography)

Courtly life included participation in literary culture. Baldassar Castiglione

As an exponent of the Turin

Prudence and knowledge descend

From Philosophy into [human] intellects;

Which are perfect as far as their disposition is concerned,

As each one receives its part of justice and reason.

To Benedetti, he so wise

And precious in the world,

Belongs so much of this [philosophy]

That it would be vain to try to equal him:

So sublime does his value shine.

All the more am I delighted that he appreciated

My painting so much so that he considered

The time and the point in which I was born in the world.

Oh splendor of our time, the sound [of your voice] silenced

Every scholar of your art, who had to direct his judgment elsewhere,

As it was overshadowed by yours, which is so deep.21

Benedetti received no formal or academic education. Like other Renaissance self-taught men (e.g., Niccolò Tartaglia

Until now I have advanced without any mentor or teacher (under the guidance of God). I have never frequented any gymnasium or school. I have not learned what the vulgar (I mean this word without arrogance) use to estimate erudition, [such as limiting it] to the time spent at school, thus setting an end to learning when the seven years [of regular studies] are ended. As long as I live, I will continue [learning].22

It is possible that Benedetti was educated privately by his father, depicted in Gaurico’s

As it is honest and right to attribute to everybody his own merit, [I should acknowledge that] Niccolò Tartagliataught only the first four of Euclid’s books to me. I studied the rest alone with effort and diligence. In fact, for the one who wants to know, nothing is [too] difficult.24

Bordiga described such self-celebration as a sign of Benedetti’s “pride in the assumed independence of his own thinking” (orgoglio di creduta indipendenza del proprio pensiero).25 This is the same pride that would later lead to animosity with other prominent mathematicians such as Del Monte

Moreover, in the preface to the Resolutio, Benedetti contrasted the simplicity of mathematics with the vanity of rhetoric. He went so far as to accuse learned and eloquent doctors of corrupting the sciences.

Furthermore, mathematics does not require much [stylistic] splendor. If some language expert tried to improve its elegance, this would have no value, because a change of the mathematical language and of the scientific terminology could easily confuse the sense [of the reasoning] and render everything obscure. Therefore, I will follow the scholarly tradition and use plain words in my demonstrations, as I disapprove of deceptive elegance. In this respect, I follow the steps of the ancients who taught the sciences and the subjects themselves using plain words. Petty teachers (indeed, charlatans and babblers) corrupted this manner of teaching. Although they do not understand the subject, their babbling obtains the highest praise by the vulgar who regard them as learned scholars. This should not be surprising, considering that the most perfect and distinguished expertise in the sciences is attained by very few—despite the fact that many people write a great deal in all kind of sciences and arts, babbling a lot and capturing the attention of the uneducated with illusions and bombastic words.26

The same tone characterized Benedetti’s next publication. Its title was intentionally polemical: Demonstratio proportionum motuum localium contra Aristotilem

As was to be expected by his irreverent tone, some of the first reactions to Benedetti’s early writings were rather critical. As he reports in the preface to the second edition of the Demonstratio (1555), some Roman

I remember that he [the very educated Doctor Peter Arches]—after many different conversations on various subjects—told me that many in Rome considered that proposition of mine (which I sent to you, Reverend Mr. Guzman , among other ones) and they mostly reacted with surprise for I did not specify that it was by no means in accordance with Aristotle’s mind. Such was the reaction of those who considered my demonstration very attentively.

They could not concede that Aristotlewas mistaken in any way, because they do not regard him as a human being. Rather, they confer upon him the celestial condition of a pagan divinity. And they see even slight disagreement as a sin. Therefore [they believe that] I committed (and still commit) heresy if, according to their judgment, I do not follow the pure and authentic mind of Aristotle’s doctrine in any manner.

Thus, in order to escape the allegation of such an error or [the rumor] that I am dissimulating and hiding something, especially as far as this issue is concerned, I decided to publish this new booklet in which I present my opinion more clearly. In this manner, everybody should become aware that I correctly understood Aristotleand that I disagree with him on a particular issue with considered reason. This is an unpleasant task for me. In fact, it is only unwillingly that I dissent with such a great man. I know nobody who could rival his excellence in all kind of doctrines. Nevertheless, his teaching is to take as true that which is supported by stronger reasons. He himself followed this precept, as he stated in the Ethics: “Plato is my friend, Socrates is my friend, but truth is even more friend to me.”32

It is evident from these passages that Benedetti regarded mathematics as a support for conclusive rational argumentation in the treatment of natural issues. Therefore, as a mathematicus he claimed for himself the right to be called a philosophus. Already in the short biographical indication accompanying his birth horoscope, he was said to be a “Phylosophus, Musicus, atque Mathematicus” (see Figure 1.2). In his publications, Benedetti often stressed his quality as “philosophus” or “filosofo.” Galileo

Thus, Benedetti not only dealt with fields of mathematical inquiry that traditionally belonged to the domain of mathematics (such as mechanics, optics, mathematical astronomy, and musical theory), but also addressed issues considered beyond the limitations of mathematics, especially terrestrial and celestial physics. The title of the Diversae speculationes mathematicae et physicae is itself provocative, as it brings together mathematics and natural philosophy (or physica), considered to be separate fields, one dealing with the quia (the “phainomena”) and the other with the propter quid (the “causes”). In this respect, Benedetti’s methodology is very close to that of Nicolaus Copernicus

Only mathematics can provide sure and unshakeable knowledge to its devotees, provided one approaches it rigorously. For its kind of proof proceeds by indisputable methods, namely arithmetic and geometry. Hence we were drawn to the investigation of that part of theoretical philosophy, as far as we are able to the whole of it, but especially to the theory concerning divine and heavenly things. For this alone is devoted to the investigation of the eternally unchanging. For that reason it too can be eternal and unchanging (which is a proper attribute of knowledge) in its own domain, which is neither unclear nor disorderly. Furthermore it can work in the domains of the other [two divisions of theoretical philosophy, physics and theology] no less than they do. For this is the best science to help theology along its way, since it is the only one which can make a good guess at [the nature of] that activity which is unmoved and separated; [it can do this because] it is familiar with the attributes of those beings which are on the one hand perceptible, moving and being moved, but on the other hand eternal and unchanging, [I mean the attributes] having to do with motions and the arrangements of motions. For almost every peculiar attribute of material nature becomes apparent from the peculiarities of its motion from place to place. [Thus one can distinguish] the corruptible from the incorruptible by [whether it undergoes] motion in a straight line or in a circle, and heavy from light, and passive from active, by [whether it moves] towards the centre or away from the centre.35

Even after Copernicus

Astrology was another area of expertise for Benedetti. During the Renaissance, astronomy and astrology were never separated. Benedetti was expected to cast horoscopes and give astrological advice to his patrons, just as Brahe

In Venice

We gathered at Mr. Domenico Venier’splace; his magnificence [came] first, followed by the most excellent Mr. Giovanni Battista Benedetti, many other gentlemen, myself (Annibale Raimondo ), and finally the ex-reverend father Pacifico of Florence (now, as an ex-friar, known as ‘excellent Mr. Francesco Giuntini ’). As soon as the latter arrived, he was given the simple astrological chart of the revolution of the magnificent Venier, without any written indication around or below. The good father took countless and endless texts and aphorisms out of his scapular. He related them to the revolution as good as a physician might give prescriptions to sick people by saying ‘God might help you.’ Since the most excellent Mr. Benedetti and myself laughed uncontainably—thereby making the father believe that he could not have better done—the good father, who was already trotting, was spurred by our laugher to gallop so quickly that it became extremely difficult to bring him back to silence and prevent him from telling more stupidities.37

An astrological report by Benedetti, cast for Carlo Emanuele I

In the concluding letter of the Diversae speculationes, Benedetti envisaged a reform of astrology. He directed this letter to a German correspondent whose name he awkwardly Latinized as Volfardus Aisestain.

As for the question whether or not I regard as true all that is written in the books of judicial astrology, I respond that I do not. I even believe that much is wrong […]. But you will be informed about all this in a special tract of mine, about which I told you on another occasion. In it, you will find many things I have proven through the evidence of many observations. I intend to publish that tract along with some other speculations of mine, if only I will have enough time to do that, before I meet the body of the adverse Mars as indicated by my horoscope. This is going to happen in 1592.39

This passage concludes his major work. In it, Benedetti predicted, using astrological means, his own death for the year 1592, but he actually died in January 1590.40 This fact aroused some doubts about his proficiency as an astrologer, especially from his successor as court mathematician, Bartolomeo Cristini

To sum up, Benedetti’s persona and work had various facets, his interests ranging from mathematics to cosmology and from natural philosophy to literature. In a certain sense, he can be seen as a Renaissance polymath. However, his profile can be better encompassed by the title of “mathematicus,” as long as we do not take it too restrictively. A Renaissance mathematician like Benedetti was an engineer and a technical inventor, as well as a theoretician and a natural philosopher; someone with teaching and civil duties who served as a counsellor, also for astrological matters. Being a court mathematician implied benefiting from high recognition and visibility in society. Thus, this professional and intellectual appurtenance had nothing to do with the rather low acknowledgment that mathematicians received at universities, where physicians, lawyers, and theologians were higher placed and received better salaries.42 The cultural environment of Turin

1.2 Benedetti’s Works and Publications

Benedetti published his first work at the age of 23, the Resolutio omnium Euclidis

In 1554 Benedetti published a Demonstratio proportionum motuum localium contra Aristotilem

After the Resolutio omnium Euclidis

In 1574 Benedetti also wrote about a trigonometrical measuring instrument of his own invention, Descrittione, uso, et ragioni del Trigonolometro. It was never printed and is preserved in manuscript form in the Civic Library of Carignano along with the Italian work on sundials, Intelligentia et compositione d’ogni sorte [di] Horologij Solari.45 His next scientific treatise, De temporum emendatione opinio (1578), proposed correcting and reforming the calendar. In 1578 the duke initiated a public disputation at the University of Turin

Next came Benedetti’s defense of the reliability of the mathematical computations underlying astrological predictions in the context of a heated polemic on this issue that burst out in Turin

Finally, Benedetti had his major work, Diversarum speculationum mathematicarum, et physicarum liber, printed in 1585. It was issued again under slightly different titles in Venice

Two of Benedetti’s manuscripts, preserved in the Biblioteca Nazionale Universitaria of Turin

Reprints of Benedetti’s works are rather scarce.

Excerpts on mechanics from Benedetti’s work were included by Stillman Drake and Israel Edward Drabkin in their Mechanics in Sixteenth-Century Italy: Selections from Tartaglia

Footnotes

Bordiga 1985, 752: “Habbiamo creato, fatto et costituito, facciamo creamo et costituiamo il detto Giovan Battista de Benedetti con tutti i suoi figliuoli maschi e femine legittimi, et naturali, nati et che nasceranno, et saranno procreati di legittimo matrimonio, con tutti loro posteri et heredi et successori in perpetuo veri nobili del Sacro Romano Imperio et nostri, et per tali li chiamiamo et dicchiariamo per dabondante (ancora ch’egli insieme coi suoi predecessori siano nobili e nati di antica prole nobili come siamo benissimo informati).”

Bordiga 1985, 752: “Emanuele Filiberto per gratia di Dio Duca di Savoia Principe di Piemonte etc. Essendoche le attioni che tendono alla Virtù, come che da quella prendano accrescimento et perfettione, sono ammirate et havute in pregio: così gl’huomini che in quelle di continuo si essercitano vengono da ogniuno istimati et tenuti in particolare consideratione, la onde havendomi sempre fatto conto delle persone che dirizzassero ogni loro pensiero al bene operare, et quanto più si potrà, cercassero col mezo delle scienze, et arti liberali sicure et vere guide alla virtù di venire alla cognizione di esso doppo l’haver noi ricercato che in questo ne sotisfacesse, massime nelle discipline matematiche. Al fine ci è pervenuto nelle mani il nobile messer Giovanni Battista de Benedetti venetiano, nostro mattematico il quale havendo consumato la maggior parte dell’età sua nelle bone lettere et studij di filosofia, et fatto professione delle dette mattematiche, et così divinamente et per eccellenza riuscito che si può dire in quelle (tra gl’altri) essere singolare cosa che si porge tal contento, et la sua servitù a noi molto grata tale soddisfattione che lo giudichiamo degno che partecipi de gl’honori dovuti alle sue virtù acciò che gl’accresca l’animo di perseverare et altri siano invitati a seguitare li suoi vestigij.”

This is why Brahe was not and could not desire to be imperial mathematician to Rudolph II, as has often been wrongly thought. See Voelkel 1999.

Brahe 1916, 250: “Accedit et hoc, quod Stellula illa Cassiopeae in toto Orbe Terrarum ob siccas illas fumositates interpositas non tam splendide apparuisset atque haec Nova, si sub hac sola constitissent, et non reliquas illi vicinas pari modo attingissent, lumineque insueto auxissent. Hoc vero ultimum egregie et solerter ex excellentissimo Philosopho IOHANNE BAPTISTA BENEDICTO PATRICIO VENETO in praeclaro illo Opere quod de speculationibus Mathematicis et Physicis inscripsit, circa finem inter Epistolas eius evidenter et dilucide, Geometricis rationibus demonstratur. Ubi ad hunc ipsum Annibalem Raimundum scribens, absurdum, quod ex eius falsa assumptione necessario sequitur, dilucide ostendit.”

See Mosley 2007.

For the broad European context of patronage and the arts in the Early Modern Period, see Bedini 1999, Moran 1981, and Moran 1991.

See Roero 1997 and Mamino 1989.

Benedetti’s advice on the calendar reform is preserved in the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana under the signature cod. Vat. lat. 5645, 148r–150r. See Ziggelaar 1983, 211–214.

“De la Filosofia nasce e discende La prudenza e ’l saper de gli intelletti; Co’ quali essendo nel dispor perfetti, A ognuno suo diritto e sua ragion si rende Di questa sì gran parte se ne prende Il saggio e raro al mondo Benedetti, Che d’agguagliarlo in vano è chi s’affetti: Tanto sublime suo valor s’estende. Però tanto godo io che sì gli piacque La mia pittura, e perciò egli volse L’ora et il punto nel qual nacqui al mondo. Splendor di questa etade al tuo suon tacque Ogn’un de l’arte tua, e altrove volse Il suo dir vinto dal tuo sì profondo.”

Benedetti 1553, f. 5r: “[…] huc usque progressus sum (Deo duce) sine monitore praeceptoreque ullo, nullum gymnasium unquam, nullamque scholam frequentavi, neque hoc studui, quod vulgus solet (sed absit verbo arrogantia) pro tempore in scholis transacto, eruditionem estimare, ac septennario finito finem studiis imponere, sed dum vivo, illa prosequi.”

One reads in the preface ad lectorem of the Diversae speculationes the following declaration: “In his autem meditandis, ex arithmeticis authoribus quos inspexi praecipuus fuit Nicolaus Tartalea, quippe quem fere omnia ab aliis scripta collegisse constat, nec alios ex praecipuis quos legere potui omittendos duxi, inter quos sunt Hieronymus Cardanus, Michael Stifelius, Gemma Frisus, Ioanna Novimagus, Cuthbertus Tonstallus, caeterique huiusmodi.”

Benedetti 1553, f. 5v: “Caeterum quia cuiusque quod suum est reddi debet, nam et pium et iustum est, Nicolaus Tartalea, mihi quatuor primos libros solos Euclidis legit, reliqua omnia, privato et labore et studio investigavi, volenti namque scire, nihil est difficile.”

Benedetti 1553, f. 5v: “Adde quod Mathematicae disciplinae, neque tantum requirunt splendorem, neque si quis peritus linguarum contendat ad elegantiam rem reducere, egregium quid effecerit, quia mutato usu Mathematicae loquendi, ipsiusque scientiae terminis, sensum facile perturbaverit, et ex nihilo nihil apprehensum obtinuerit. Quare morem scholarum sequutus, obstentatione elegantiae explosa, verbis nudis in demonstrationibus usus sum, hac in parte veterum vestigia sequutus, qui nudis verbis scientias resque ipsas docebant, quem modum docendi, nobis devastarunt scioli vel potius circulatores, garruli, rebus ipsoque iudicio destituti, garrulitate siquidem apud vulgus, laudem summam consequuntur, et pro doctis circunferuntur, nec mirum, cum scientiarum perfecta exquisitaque perita, paucissimis detur, non obstante quod multi permulta de omnis generis et scientiis et artibus scribant, permultaque garriant, fucis suis, et ampullis imperitorum oculos perstringentes […].”

Taisner 1562, see the discussion in Maccagni 1967a, 344–455, n. 13.

Maccagni 1967b, 20–21: “Memini eum [eruditissimum Doctorem Petrum Arches], post varia et diversa colloquia utro citroque inter nos habita, mihi retulisse quamplurimos Romae, conspecta mea illa propositione quae ultra reliquas tuae R[everende] D[omine] [Guzman]a me mittebatur, valde mirari solitos me addidisse illam neutiquam esse iuxta mentem Aristotelis, idque ab eis dictum ubi meam demonstrationem attentius considerarunt.

Ne vero Aristotelem ullo modo errasse concederent, cum illum non infra humanae conditionis terminum habeant, sed potius veluti coeleste quoddam numen sibi proponant, censeantque nefas esse si vel latum quidem unguem ab eo quis dissentiat, in hac potius haeresi fuisse, ac etiamnum esse, ut me germanum et genuinum sensum Aristotelicae opinionis nequaquam ex authoris mente assecutum existiment.

Ego vero ne mihi diutius talis impingatur error, neve quid maxime super hac re sentiam, aut dissimulem, aut reticeam, statui, hoc novo libello edito, meam sententiam clarius aperire, ut omnes intelligant me et Aristotelem ipsum antea recte intellexisse, et non temere hoc in loco ab eo discrepare, quod sane quanquam invitus facio (nec tamen libenter a tanto viro diversum sentio, quippe qui norim quam ille praeclarus extiterit in omni doctrinarum genere), docet tamen maiorem ratione veritatis habere, quo ipsemet facendum censuit, quam inquit in Ethicis: ‘Amicus Plato, amicus Socrates, at magis amica veritas.’”

A very informed case study on astrology at Italian Renaissance courts is Azzolini 2013.

Raimondo 1574: “Ritrovandosi nella camera del Clariss. M. Dominico Veniero prima la sua Mag.[,] lo eccellentissimo M. Gio. Battista Benedetti, molt’altri gentilhuomini, et Annibale Raimondo, che son quel io, vi sopraggiunse al’hora il Reverendo Padre Frate Pacifico Fiorentino de gli bene inculati, adesso per essersi sfratato lo Eccellente M. Francesco Giuntini, alquale, subito giunto, fu dato in mano la figura simplice del cielo della Revolutione del detto Mag. Veniero, senz’altra scrittura intorno, né appresso, il buono padre alhora mise mano al suo scapolario et cavò fuori testi, et afforismi senza fine, et senza fondo, allegandoli tanto a proposito della Revolutione, quanto facea quel buon medico le ricette che ’l dava ai suoi infermi, quando le dicea Dio te la mandi buona, et perché lo Eccell. M. Gio. Battista Benedetti et io se smassellavamo dalla risa, ben però in modo di maravigliarsi, come non fusse possibile a dir meglio di quello che dicea sua paternità, il buon padre per il nostro ridere sì come prima andava trottando, si misse a correr’ de modo che fu gran fatica a poterlo tenere et farlo tacere che’l non dicesse più minchionerie.” Cf. Corradeschi 2009, 111, n. 46. On Raimondo and Giuntini, see Ventrice 1989, 140–145.

Benedetti 1585, 425–426: “Circa vero id de quo me interrogas, scilicet, utrum putem omnia vera esse, ea quae scripta reperiuntur in libris Astrologiae iudiciariae, respondeo quod non, imo puto plurima falsa esse […]. Sed diffusius haec omnia videbis in meo illo particulari tractatu, de quo tibi alias dixi, in quo multa videbis, quae omnia ab experientia, ex multis a me observatis, comprobata sunt, quem quidem tractatum cum quibusdam aliis meis speculationes in lucem producere cupio, si fieri poterit, antequam ad directionem mei Horoscopi cum corpore Martis Anaeretae perveniam, quae quidem directo circa annum millesimum quingentesimum nonagesimum secundum eveniet.”

Benedetti was not the first mathematician who tried to forecast his own death. Among his predecessors are famous the cases of Johannes Stöffler and Girolamo Cardano. Cf. Omodeo 2014b, 3–4.

On the lower status of mathematicians, see Henry 2011.

Clara Silvia Roero published Benedetti’s letter to Carlo Emanuele I (Turin, 19 October 1589), the index of the manuscript on gnomonics, as well as an excerpt from the manuscript on the mathematical instrument trigoniometro as appendices II and III of Roero 1997.

Giuntini 1582, 95–96: “La qual questione ha resoluta molto dottamente lo eccellente filosofo, il signor Giovambattista Benedetti mathematico del serenissimo signor Duca di Savoia, contra il filosofo Berga, famoso lettore nella università di Turino: il quale contra l’opinione del signor Piccolomini defende che l’acqua è maggiore della terra: e il Benedetti defende il contrario in favore della verità: cioè che l’acqua è minore della terra.”