For one thing after other will grow clear, […]

Thus things for things shall kindle torches new.1

2.1 Studies and Influences

It is by now widely recognized that early modern science is as much about theories as it is about communication, travel, fieldwork, and exchange of information and objects. As we have seen, the case of Antonio Vallisneri is no exception to this thesis. Interestingly, it also applies to the history of science. On my part (in all due proportion, and humbly), I am no exception.

With respect to medicine and

Obviously, I cannot claim the honor of having, or of having had, any long-lasting or significant impact on any scholar other than myself. However, in regards to my approach to the history of science, it is undeniably the result of many different academic, scholarly, and educational influences—which, in turn, derive from various professional backgrounds, experiences, suggestions, and points of view. I acknowledge this fact with pride and gratefulness.

In 2003, when I first became interested in historical research, I was still a MA student in natural sciences at the

Being an historian of science (and, furthermore, the coordinator of the Vallisneri National Edition), Generali introduced me to a scholarly tradition dating back to the beginning of the XX century. He himself had studied philosophy at the

Throughout the first and second halves of the XX century, this school developed some strong (though partial) affinities with the concept of critical rationalism upheld by

Such was the cultural context from which the National Edition of Vallisneri’s Works emerged, and by which—thanks to the teachings and advice I received from

A further crucial step in my scholarly development occurred in 2006, when I became interested in the Earth sciences in early modern Europe, and in Vallisneri’s contribution to this subject, after starting my Ph.D. at the

Like

By joining

At the

The years I spent working as an

-

Achieving this latter goal was no easy task for us. New skills had to be acquired, and new challenges had to be faced. We needed to harmonize the methodology used for the construction of a critical edition—which is typically meant to be the conclusive version of a given text15—with digital publication’s new features which, by definition, imply the ideas of continuous improvement and change. Thus, I and my supervisors

From this truly interdisciplinary, collective, cumulative, and scientific work I gained new competencies, a new book, and what so far is the most important landmark in my professional career. However, I also gained something even more precious, whose importance stretched well beyond the professional sphere and changed my personal life and my view of the world. I had become proudly aware, like never before, that I was an active part of a community and, before and above all else, that it was within this context that my work made sense.

All too often scholars forget—or worse, neglect—this simple and vital fact. On my part, I will not commit such an error again.

2.2 Note on the Text: Transcription

This critical edition of Vallisneri’s Primi Itineris Specimen is based on a single source text, the draft version held at the

The text is written for the most part in Latin. Only a few significant paragraphs in the main manuscript (pp. V.r–VI.r) and in the additional papers (pp. XXVI.r, XXIX.r, XXX.r, and, partially, pp. XXVII.r, XXIX.v, and XXXI.r) are in Italian. The criteria used for the transcription conform essentially, though not entirely, to the editorial principles developed by the National Edition of Antonio Vallisneri’s Works as these are extensively outlined and discussed by

2.2.1 Transcription guidelines

As a general rule, the spelling, punctuation, grammar, capitalization, and paragraph formatting of the original manuscript have been preserved. With the exception of the parts in Italian, and with a few exceptions for the Latin text, original abbreviations—for example, contractions (the omission of medial letters: e.g. “obblig.mus” for “obbligatissimus”; “v.ae” for “vostrae”) and suspensions (the omission of terminal letters: e.g. “lib.” for “liber”; “tab.” for “tabula”)—have not been expanded. However, superscript and subscript letters, whether abbreviated or not (e.g. “ill.mus”; “minerarum”; “non”; “quae”; “praedictam”; etc.), have always been lowered—or, accordingly, raised—to the line (“ill.mus”; “minerarum”; “non”; “quae”; “praedictam”; etc.). Likewise, cautious modernization and normalization have been made wherever the clarity of the original text was compromised by extremely difficult or uncommon (though correct) abbreviations and variants of Latin words, or by obvious misspellings and errors, or by misleading punctuation and/or capitalization. In any case, all editorial interventions and corrections have been conveniently specified and explained in the philological notes, where words and passages from the transcription are written in normal font, and editorial comments are rendered in bold (e.g. “In the text: Provincia”; “In the text: enucleatione”; “These lines are written in regular font”; “From this point on, text at p. 22 continues on the recto of an additional, unnumbered paper (XIII)”).

In accordance with a widely held typographical convention, all the underlined words, phrases and passages from the manuscript have been rendered in italics in the transcription.

2.2.2 Variants

Many letters, words, passages, and—often—entire paragraphs in the manuscript are marked for deletion with either a strikethrough or with black ink scribbling. In most cases, the content of these deleted parts is as rich and significant as the content of the main text, providing the reader with crucial data on the author’s original intention and on the development of his thought. In order to preserve the textual information in its entirety, all variants have been inserted in the philological notes: deleted text is rendered in italics and indicated in its phrase context, and normal text is rendered in normal font. For example, a variant in the manuscript is explained as follows:

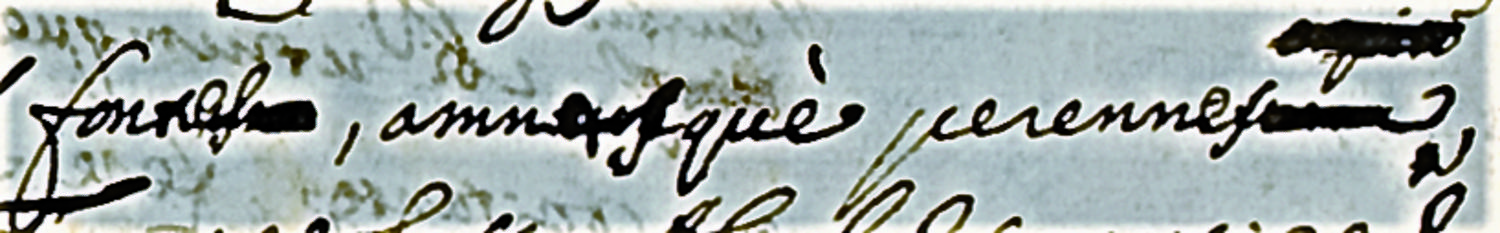

Text in the manuscript (facsimile):

Transcription (main text):

fontes, omnesque perennes qui

Transcription (philological note):

fontium, omniumque perennium copiarum qui

When a word in the manuscript is marked for deletion and specifically replaced with another term, the new variant (in normal font) always follows the deleted one (in italics) at the end of the corresponding philological note. For example:

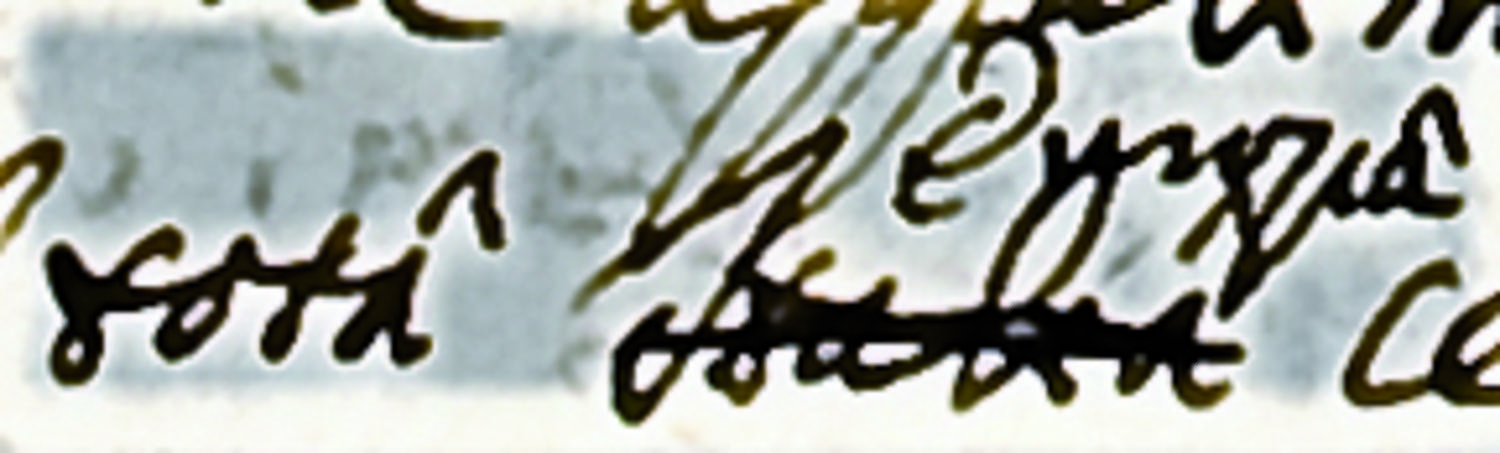

Text in the manuscript (facsimile):

Transcription (main text):

tota Europa

Transcription (philological note):

tota Italia Europa

2.2.3 Integrations

Editorial insertions are provided in case of uncertain readings, or in case of missing, illegible, or damaged text. Both in the transcription and in the philological notes, these integrations are indicated by angle brackets (e.g. “qui<bus>”; “<maxime acta>”). Ellipses within angle brackets indicate partially, totally illegible, or missing text (“<…>”; “<…>lino-nitrosum”; “<…d…>i”; “<…f…ex…>”). Editorial insertions can concern both the main body of the transcribed text and the philological notes.

A different kind of integration is provided in the historical and scientific notes, where editorial omissions in the quoted passages are indicated by ellipses within square brackets (e.g. “ammites vel ammonites […] ovis piscium similes”; “life was sustained […] through the presence of a life spirit”; “Leguminum specie lapidem quidam inveniuntur, pisis […] aut lentibus similes […]”).

2.2.4 Margin notes

The manuscript features several margin notes or “marginalia.” These have been transcribed and inserted in the philological notes where—as remarked above—transcribed text is in normal font and editorial comments are rendered in bold. For example, a margin note in the left (or right) margin is indicated with a reference number placed after the closest word in the main body of the manuscript and is explained as follows: “Margin note (right): Volve unam paginam”; “Margin note (left): De Thermal. Aq. Cap. 25, pag. mihi 324”; “Margin note (left): Nimis implicata <…> periodus.”

2.2.5 Page numbering

The manuscript pages are numbered with a combination of Roman and Arabic numerals. The Arabic numbering (1–54) is the one provided by the author, whereas the unnumbered folios (the several additional papers in the main manuscript, the eight additional papers not included in it, and both the maps) have been assigned by the editor with Roman numerals (I–XXXIII). Each unnumbered folio, in turn, has a recto (r) and a verso (v) side which are specified accordingly (I.r, I.v, II.r, II.v, III.r, III.v, … etc.). Both in the transcription and in the translation, the passage from one page to the next is marked by the number of the ending page, which is printed in bold charachters and followed by a closing square bracket in normal font (e.g. 17]; 34]; XVIII.r]; XXVII.v]).

In the facsimile section, manuscript page numbers are given in normal font at the top of each page. Each manuscript page number is followed by the sequence number (expressed in Arabic numerals, in normal font, and within parentheses) of the corresponding digital file (e.g. 26 (049); XVIII.v (063); XXIX.r (106)).

2.3 Note on the Text: Translation

The English translation of the Primi Itineris Specimen includes the same apparatus for historical and scientific notes that is featured in the transcription. Accordingly, this set of notes is also marked with Arabic numerals (1, 2, 3, … etc.), and each chapter is numbered independently.

The page numbering in the translation coincides with the numbering given in the transcription.

2.3.1 Translation guidelines

Unlike the transcription, where most of the original abbreviations in the Latin text have not been expanded, all contractions and suspensions have been silently extended in the translation. For example: “l./lib./libr.,” i.e. “liber,” is rendered as “book”; “c./cap.,” i.e. “caput,” is “chapter”; “t./tab.,” i.e. “tabula,” is “table”; “a./an./ann.,” i.e. “annus,” is “year”; “f./fig.,” i.e. “figura,” is “figure”; etc. Accordingly, the same procedure has been followed for honorary and formal appellations (for example: “Ill.us/Ill.mus,” i.e. “Illustrissimus,” is rendered as “Most Illustrious”; etc.). The only exception is the Latin word “pagina” (“page”), whose abbreviations and plural form (“p./pag./pagina/paginae”) are rendered as “p./pp.” in the translation.

As a general rule, toponyms (cities, provinces, regions, mountains, rivers, etc.) have been written in normal font—even when they are in italics in the transcription—and translated into Italian (e.g., “Regium” is rendered with the Italian name “Reggio”; etc.). Latin has been maintained in the case of names with no modern equivalents (for example, “Armorum Pratum”). Exceptions were made for English translations of Italian and European toponyms that are widely and currently used: for example, “Apeninus” is not rendered with the Italian name “Appennino” but with the English “Apennine”; “Roma” is translated as “Rome”; etc.

Technical and/or specific terms with modern English equivalents have been written in normal font (even those that are in italics in the transcription) and translated: thus, “nitrosum” becomes “nitrous”; “vitriolum” is “vitriol”; etc. Dialect and slang terms have been rendered in italics, and have not been translated (e.g. “cretone”; “canopi”; “filone”; “scaiola”; “salsa”; etc.).

2.3.2 Quotations

In the translation, all book titles are written in their original language, in full, and in italics (e.g. “as Jüngken attests in his Chymia Experimentalis, in the chapter on sulphur”; “Sir Fulvio Azzari, in Compendio dell’historie della Città di Reggio, writes that”).

Prose quotations have been translated, written in normal font, and included within English quotation marks (“”) in the main body of the text (e.g. “I shall use the words of Saint Jerome: “They do not embellish the face by artificial means, with purple, nor do they arrange towering crowns with strange ornaments.” Neither Minerva, nor Ceres, nor Bacchus dispenses his gifts in that place”).

Poetry passages have been translated, written in normal font, and placed in block quotations: these are indented and separated from the main body of the text, and are without quotation marks. For example:

“Claudian, in Panegyricus de Consulatu Manlii, De Monte Olimpo:

He rises above the rains, hears the rushing clouds beneath his feet, and treads upon the roaring thunders.

So was I when I was in the mountains, etc.”

2.3.3 Integrations

Like the transcription, editorial insertions are provided in case of uncertain readings or in the case of missing, illegible, or damaged text. These integrations are indicated by angle brackets (e.g. “<I> pound”), and ellipses within angle brackets denote illegible or missing text (e.g. “<…>”; “of <…> false”; “did <…> <…>y they”). In addition, the translation includes another kind of editorial insertions; these have been added wherever a strictly literal rendering of the Latin text was too unclear or ambiguous, and additional words were necessary to clarify the sense of a sentence. Such integrations are indicated by square brackets (e.g. “it covers about three hundred [square] feet”; “it can be seen not far [from there]”; “of which I will [speak] later”).

As stated above, in the case of passages quoted in the historical and scientific notes editorial omissions are indicated by ellipses within square brackets (e.g. “ammites vel ammonites […] ovis piscium similes”; “life was sustained […] through the presence of a life spirit”; “Leguminum specie lapidem quidam inveniuntur, pisis […] aut lentibus similes […]”).

2.3.4 Margin notes

Consistent with what has been done in the transcription, all margin notes have been translated and inserted in footnotes where they have been marked with lower-case letters in italics (and numbered in alphabetical order: a, b, c, … z, aa, ab, ac, … etc.). As for the philological notes, translated text is in normal font and editorial comments are rendered in bold. For example, a margin note in the left (or right) margin is indicated with a reference number placed after the closest word in the main body of the manuscript, and is explained as follows: “Margin note (right): Turn one page”; “Margin note (left): De Thermalibus Aquis, Chapter 25, p. 324 of my [book]”; “Margin note (left): The <…> sentence is too complicated.”

2.3.5 Capitalization

In the translation, the capitalization of words conforms to English grammar rules. For example, the Italian term “agosto” is rendered as “August”; the Latin “gallicus” becomes “Gallic”; etc. All honorary and formal appellations have been capitalized whether or not they have an uppercase initial in the Latin text (e.g. “viri Gravissimi” is rendered as “Most Severe Men”; “amicorum optime” is “O Best Friend”).

2.3.6 Numbers

The rendering of numbers—whether written in digits, in words, or in Roman numerals—conforms to the style of the Latin manuscript. For example, “bis centum” is rendered as “two hundred”; “vigintiquatuor mille” is “twenty-four thousand”; “XII” is “XII”; “189” is “189”; etc. This rule applies even to ordinal numbers (e.g. “tertium” is “third”; “5°” is “5°”).

The rendering of numbers with decimal and thousands separators conforms to English writing conventions. Therefore, in the translation a period is used to indicate a decimal place and a comma is used to indicate groups of thousands (e.g. “1.000,012” is rendered as “1,000.012,” etc.).

Footnotes

“Namque alid ex alio clarescet, […] Ita res accendunt lumina rebus” ((Lucretius n.d.), I, 1115–1117. English translation: (Lucretius 1916), http://data.perseus.org/citations/urn:cts:latinLit:phi0550.phi001.perseus-lat1:1.1083).

See http://www.vallisneri.it; http://www.olschki.it/la-casa-editrice/collane-Olschki/edizioni-nazionali/edizione-nazionale-Vallisneri. For many years, the National Edition has produced many important studies, critical editions and digital humanities projects, thereby affirming itself as one of the most lively and renowned cultural institutions of this kind in Europe. As such, it has recently joined the ISCH COST Action IS1310—“Reassembling the Republic of Letters, 1500–1800,” a digital framework for multi-lateral collaboration on Europe’s Intellectual History (http://www.republicofletters.net/).

The proceedings of the meetings were published by the Vallisneri National Edition in (Dal Prete, Generali, and Monti 2011); (Facchin and Spiriti 2011); (Generali 2008); (2011b); (Generali and Ratcliff 2007); (Monti 2011).

The proceedings of the meeting were published in (Kölbl-Ebert 2009).

The proceedings of the meeting were published in (Ortiz et al. 2011).

The proceedings of the meeting were published in the journal Earth Sciences History, 34 (2), 2015.

This subject is still a matter of debate among scholars. A very interesting (though, in my opinion, not entirely convincing) point of view about the issues, goals, and methodologies of textual criticism and critical editions is provided by James Hankins, General Editor of the I Tatti Renaissance Library: http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:6314663.

http://www.vallisneri.it/criteri.shtml. Concetta Pennuto’s Note on the Text is in (Vallisneri 2004), LXXXV–XCIII. The same guidelines have been extensively outlined and discussed by other authors in (Vallisneri 2007), IX–XXXV; (Vallisneri and Cogrossi 2005), 25–27, 85–89; (Vallisneri 2006), CXXXV–CXLVI; (2011), LXXI–LXXXI; (2009), CXCI–CXCVII; (Vallisneri and Davini 2010), LXIX–LXXVIII; (Vallisneri 2012), LXI–LXVI.