|

FRONTESPIZIO - Primo folio (non numerato), recto |

FRONTISPIECE - First folio (unnumbered), recto |

|

|

Frontispiece  Diſciplinæ Mathematicæ loquuntur[.] Qui cupitis Rerum varias cognoſcere cauſaſ[.] Diſcite noſ, cunctiſ hac patet una uia. |

The Mathematical Disciplines say, whoever strives to investigate the reasons to think, study us, this way is open to everyone. |

|

INCIPIT - Primo folio (non numerato), verso |

INCIPIT - First folio (unnumbered), verso |

|

|

Incipit INVENTIONE DE NICOLO TARTAGLIA Briſciano Intitolata Scientia Noua diuiſa in V libri, nel Primo di quali ſe dimoſtra theoricamente, la natura, & effetti de corpi egualmente graui, in li dui contrarii moti che in eſſi puon accadere, & de lor contrarii effetti. In lo ſecondo (geometricamente) ſe approua, e dimoſtra la qualita ſimilitudine, et proportionalita di tranſiti loro ſecondo li uarij modi, che puono eſſer eietti, ouer tirati uiolentemente per aere, et ſimilmente delle lor diſtantie. In lo terzo ſe inſegna una noua pratica de miſurare con l’aſpetto, le altezze diſtantie ypothumiſſale, et orizontale delle coſe apparente, giontoui anchora la theorica, cioe la ragione et cauſa di tal operare. In lo quarto ſe dara la proportione de l’ordine dil creſcere callar che in ogni pezzo di artegliaria nelli ſuoi tiri, alzandolo ouer arbaſſandolo, ſopra il pian de l’orizonte, et ſimilmente ogni mortaro, anchora ſe inſegnara il modo di trouar tutte le dette uarieta, ouer quantita de tiri in ogni pezzo de artegliaria, ouer mortaro mediante la notitia dun tiro ſolo. Anchora ſi mostrara il modo come ſi debbia gouernar un bombardiero quando deſidera, di battere ouer di percottere in qual che luoco apparente. Oltra di queſto ſe inſegnara anchora il modo come ſi debbia gouernar il detto bombardiero quando gli fuſſe fatto un riparo dauanti al luoco doue percote uolendo pur percottere nel medemo luoco per altra uia, ouer elleuatione quantunque piu non ueda quel tal luoco. Anchora ſe dara il modo di ſapere percottere continuamente la oſcura notte in un luoco appoſtato il giorno auanti. |

INVENTION OF NICOLO TARTAGLIA from Brescia entitled Nova scientia, divided into five books.1 In the first book, the nature and effects of equally heavy bodies are theoretically demonstrated as well as the two contrary motions that can affect such bodies and the contrary effects of such motions. In the second [book], the qualities, similarities and proportions of the transits, and therefore of the distances, of such bodies are shown and demonstrated (geometrically) according to the various ways in which the bodies can be ejected, that is, thrown violently through the air. In the third [book], a new practice to measure by sight the height and the diametral and horizontal distances of the perceptible objects is taught. The theory, that is, the reason and the cause of such operations, is also added. In the fourth [book], the ratio is described between the increase [and] decrease of the shots of each piece of artillery and the elevating or lowering of the piece above the plane of the horizon. Similarly [the same will be shown] for each [type of] mortar. Moreover, the method of how to find all the mentioned varieties is taught, that is, the quantitative information concerning the shots of each piece of artillery and mortar on the basis of information concerning one single shot. In addition, the method is given of how a bombardier must proceed when he intends to hit or strike a certain perceptible place. In addition, the method is also taught of how the mentioned bombardier should proceed when the place he intends to strike has been covered with a protective shield [so that he can] strike it using another path, that is, using another elevation, even though he is no longer able to see that place. Again, the method is shown of how to continuously strike during the night a place that has been targeted earlier in the day. |

|

INCIPIT - Primo folio (non numerato), verso - cont. |

INCIPIT - First folio (unnumbered), verso - cont. |

|

|

In lo quinto libro ſe dechiarira (ſecondo l’autorita de molti Eccellentiſſimi Naturali) la natura, et origine de diuerſe ſpecie di gome, olei, acque ſtillate, anchora de diuerſi ſimplici minerali et non minerali dalla natura prodotti, et da l’arte fabricati, anchora ſe manifeſtara alcune ſue particolare proprieta circa a larte de fuochi. Et ſimilmente ſe delucidara quale ſono quelle materie chi ſe conuiengono et che ſe accordano et quale ſono quelle che non ſi conuiengono ne ſe accordano, a ardere inſieme, et conſequentemente ſe dara il modo di componere, uarie et diuerſe ſpecie de fuochi, non ſolamente alla defenſione de ogni murata terra utiliſſimi, ma anchora in molte altre occorentie molto a propoſito. |

The fifth book discloses (according to the authority of many very Excellent Naturals2) the nature and the origin of several kinds of gum, oil, distilled water, and also several simple and not simple minerals produced by nature and manufactured by art. Then, some particular characteristics of the art of the fires3 are clarified. Similarly, it is then explained which materials burn well together and which materials are not appropriate for this purpose. Consequently, the method is described of how to compound various and different kinds of fires, which are not only very useful for defending fortified land, but also very appropriate for many other occasions. |

|

EPISTOLA - Secondo folio (non numerato), recto |

EPISTLE - Second folio (unnumbered), recto |

|

|

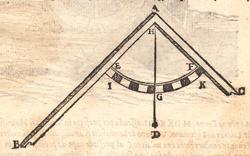

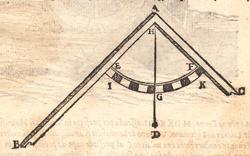

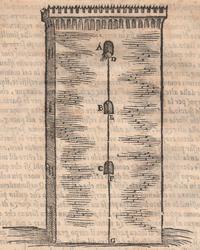

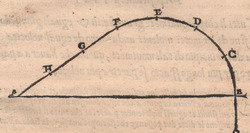

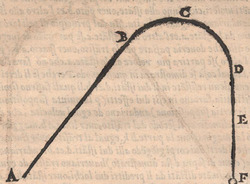

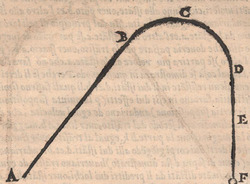

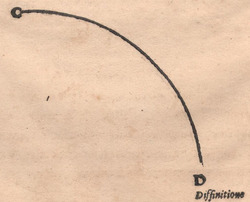

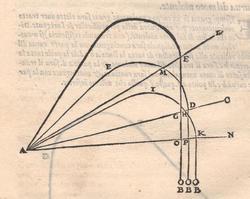

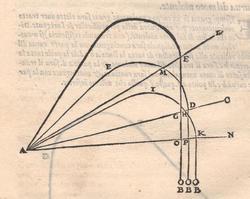

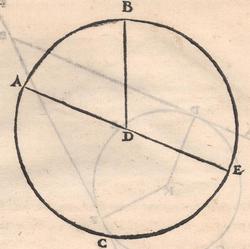

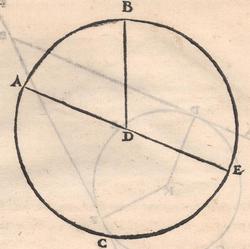

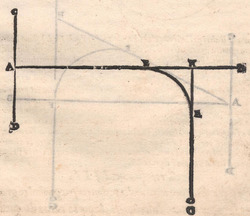

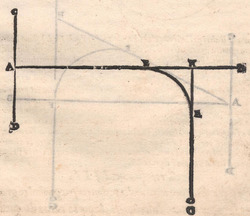

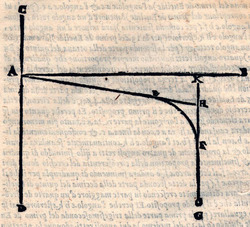

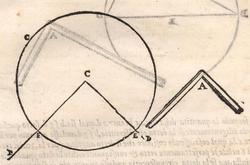

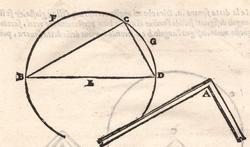

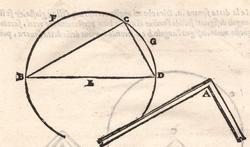

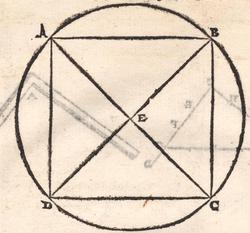

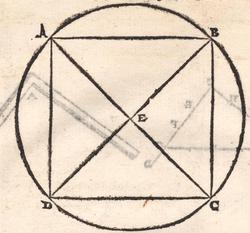

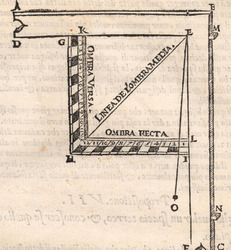

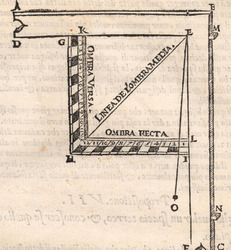

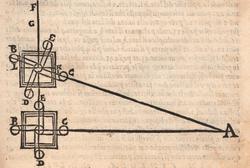

ALLO ILLVSTRISSIMO ET INVICTISSIMO SIgnor Franceſcomaria Feltrenſe dalla Rouere Duca Eccellentiſſimo di Vrbino et di Sora, Conte di Montefeltro, et di Durante. Signor di Senegaglia, et di Peſaro. Prefetto di Roma, et dello Inclito Senato Venetiano Digniſſimo General Capitano. Epistle HABITANDO in Verona l’Anno MDXXXI Illuſtriſſimo. S. Duca mi fu adimandato da uno mio intimo et cordial amico Peritisſimo bombardiero in castel uecchio (huomo atempato et copioſo di molte uirtu) dil modo di mettere a ſegno un pezzo de artegliaria al piu che puo tirare. E a ben che in tal arte io non haueſſe pratica alcuna (perche in uero Eccellente Duca) giamai diſgargeti artegliaria, archibuſo, bombarda, ne ſchioppo niente dimeno (deſideroſo di ſeruir l’amico) gli promisſi di darli in breue riſſoluta riſposta. Et dipoi che hebbi ben masticata et ruminata tal materia, gli concluſi, et dimoſtrai con ragioni naturale, et geometrice, qualmente biſognaua che la bocca del pezzo steſſe elleuata talmente che guardaſſe rettamente a 45 gradi ſopra a l’orizonte, et che per far tal coſa iſpedientemente biſogna hauere una ſquara de alcun metallo ouer legno ſodo che habbia interchiuſo un quadrante con lo ſuo perpendicolo come di ſotto appar in diſegno, et ponendo poi una parte della gamba maggiore di quella (cioe la parte BE) ne l’anima ouer bocca dil pezzo disteſa rettamente per il fondo dil uacuo della canna, alzando poi tanto denanti il detto pezzo che il perpendicolo HD ſeghi lo lato curuo EGF (dil quadrante) in due parti eguali (cioe in ponto G) All’hora ſe dira che il detto pezzo guardara rettamente a 45 gradi ſopra a l’orizonte. Perche (Signor clarisſimo) il lato curuo EGF del quadrante (ſecondo li aſtronomi)

|

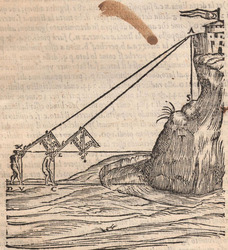

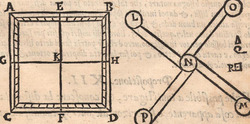

TO THE MOST ILLUSTRIOUS AND HIGHLY RESPECTED Lord Francescomaria Feltrense Della Rovere, Very Excellent Duke of Urbino and of Sora, Count of Montefeltro and of Durante, Lord of Senigallia and of Pesaro, Prefect of Rome and Very Worthy General Captain of the Illustrious Senate of Venice. During the year 1531, when the Most Illustrious Lord Duke was living in Verona, I was asked by a close and kind friend of mine, a very skilled bombardier at the Castel Vecchio4 (an aged man with many virtues), about the method to set up a piece of artillery in such a way that it shoots the farthest. Although I did not have any experience in such an art (because the truth is, Very Excellent Duke, I have never discharged any artillery, or harquebus, or bombard or rifle5), I nevertheless (as I wished to serve a friend) promised to quickly provide him with a resolute answer. After I had carefully contemplated and ruminated this subject, I concluded and demonstrated to him by means of natural and geometrical arguments that the mouth of the piece had to be elevated so that it addresses straightly [the inclination of] 45 degrees above the horizon. Moreover, [I told him] that to accomplish this quickly, a square of whichever metal or hardwood is needed. The square must contain a quadrant with its plumb line [positioned] as it appears below in the drawing. Then, one inserts part of the longer side of the square (that is the part BE) into the bore or mouth of the piece, laying it flat along the bottom of the empty barrel, and one lifts up the front of the mentioned piece until the plumb line HD divides the curved side EGF (of the quadrant) into two equal parts (that is at the point G). At this point, one can say that the mentioned piece is straightly elevated at 45 degrees above the horizon. Since (Very Illustrious) the curved side EGF of the quadrant is (according to the astronomers)

|

|

EPISTOLA - Secondo folio (non numerato), verso |

EPISTLE - Second folio (unnumbered), verso |

|

|

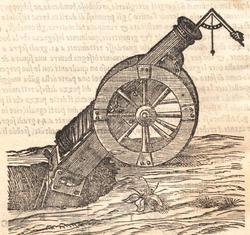

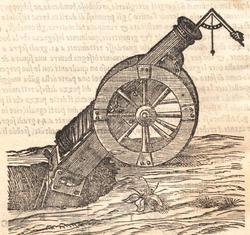

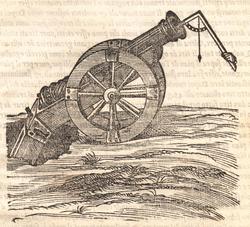

ſe diuide in 90 parti eguale, et cadauna di quelle chiamano grado. Pero la mita di quello (cioe GF) uerria a eſſer gradi 45. Ma per acordarſe con quello che ſe ha da dire lo hauemo diuiſo in 12 parti eguali, et accioche uoſtra Illuſtriſsima D. S. ueda in figura quello che diſopra hauemo con parole depinto hauemo qua diſotto deſignato il pezzo con la ſquara in bocca aſſettato ſecondo il propoſito da noi conchiuſo al detto noſtro amico. La qual concluſion a eſſo parſe hauer qualche conſonantia pur circa cio dubitaua alquanto parendo a lui che tal pezzo guardaſſe troppo alto. Il che procedeua per non eſſer capace delle nostre ragioni, ne in le Mathematice ben corroborrato, niente di meno con alcuni iſperimenti particolari in fine ſe uerifico totalmente coſi eſſere. Pezzo elleuato alli 45 gradi ſopra a l’orizonte.  Ma piu ne l’anno MDXXXII eſſendo per prefetto in Verona il Magnifico miſſer Leonardo Iuſtiniano. Vn capo de bombardieri amiciſſimo di quel nostro amico. Venne in concorrentia con un’altro (al preſente capo de bombardieri in Padoa) et un giorno accadete che fra loro fu proposto il medemo che a noi propoſſe quel noſtro amico, cioe a che ſegno ſi doueſſe aſſetare un pezzo de artegliaria che faceſſe |

divided into ninty equal parts and each of these is called a degree, then its half (that is GF) is 45 degrees. Appropriately to what we have to say,6 we [however] divide it [the quadrant] into twelve equal parts. To let Your Most Illustrious Ducal Lordship see in a figure what we have described above in words, we have drawn the piece [of artillery] with the square placed in the mouth of the piece in a figure below, positioned according to the argument concluded for our mentioned friend. Although it seemed to him that this conclusion contains some truth, he nevertheless suspected that the piece was elevated too much. This occurred because he was unable to understand our arguments and because he was not practiced in mathematics. In the end, however, the truth of the argument was verified by means of certain specific experiments. A piece elevated at 45 degrees above the horizon.  During the year 1532, moreover, the Prefect of Verona was the Magnificent Sir Leonardo Iustiniano, chief bombardier and very close friend of our friend. He and another (now chief bombardier in Padoa) challenged each other and one day happened to argue about the same question suggested to us by our friend, that is, the elevation at which a piece of artillery has to be set in order to accomplish |

|

EPISTOLA - Terzo folio (non numerato), recto |

EPISTLE - Third folio (unnumbered), recto |

|

|

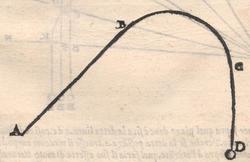

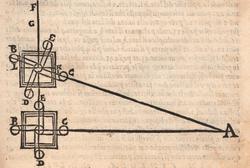

il maggior tiro che far poſſa ſopra un piano. Quel amico di quel nostro amico gli concluſe con una ſquara in mani il medemo che da noi fu terminato cioe come di ſopra hauemo detto et deſignato in figura. L’altro diſſe che molto piu tiraria a dui ponti piu baſſo di tal ſquara (la quale era diuiſa in 12 parti) come diſotto appare in diſegno.  Et ſopra di questo fu depoſta una certa quantita de danari, et finalmente ueneno alla ſperientia, et fu condotta una colobrina da 20 a Santa Lucia in campagna, et cadauno di loro tiro ſecondo la propoſta ſenza alcun auantaggio di poluere ne di balla, onde Quello che tiro ſecondo la nostra determinatione, tirò di lontano (ſecondo che ne fu referto) pertiche 1972 da piedi 6 per pertica, alla ueroneſa, l’altro che tirò li dui ponti piu baſſo, tirò di lontano ſolamente pertiche 1872 per la qual coſa tutti li bombardieri, et altri ſe uerificorno della noſtra determinatione, che auanti di queſta iſperientia ſtaſeuano ambigui imo la maggior parte haueuano contraria opinione parendoli che tal pezzo guardaſſe tropo alto. Ma piu forte uoglio che uostra preclariſsima Signoria ſappia che di tre coſe è forza che ne ſia una, ouer che li miſuranti ferno errore nel miſurare, ouer che a me non fu refferto il uero, ouer che il ſecondo cargo piu diligentemente dil primo. Perche la ragione ne demostra |

the longest possible shot over a plane. That friend of our friend with a square in his hands came to the same conclusion we did, that is, as we said above and drew in the figure. The other [bombardier] said that it would project much further were it set two points lower within that square (which was divided into twelve parts) as it appears in the drawing below.  A certain quantity of money was bet on this [question] and they finally arrived at the experiment. A culverin of twenty [libra] was brought to the countryside around Santa Lucia.7 Each of them shot according to what they suggested and without any difference in reference to the ball and to the charge. The one who shot according to our conclusion reached (according to what was referred) 1972 perches, [where] each perch is [constituted] of six feet of [the measurement system of] Verona. The other, who shot two points lower, reached only 1872 perches. For this reason, all the bombardiers and the other persons recognized the truth of our conclusion, although before the experiment they had doubted it and most of them had been of the contrary opinion as it seemed to them that the piece was elevated too much. But I want Your Most Illustrious Lordship to understand the subject better and of the three [following] statements it is necessary that only one is true: either the measurers made a mistake while measuring, or I was not told the truth, or the second charge was more diligently prepared than the first. Because8 according to the argument it is demonstrated |

|

EPISTOLA - Terzo folio (non numerato), verso |

EPISTLE - Third folio (unnumbered), verso |

|

|

che il ſecondo (cioe quello che tiró li dui ponti piu baſſo[)] [tirò] alquanto piu dil dovere alla proportione del primo, ouer che il primo tirò alquanto manco di quello che doueua tirare alla proportione del ſecondo, come nel quarto libro (doue trattaremo de la proportion di tiri) in breue quella potra conoſcere e uedere. Et ſappia uostra Magnanimita che per eſſer stato all’hora in tal materia desto deliberai di uoler piu oltra tentare. Et cominciai (et non ſenza ragione) a inuiſtigare le ſpecie di moti che in un corpo graue poteſſe accadere, onde trouai quelle eſſere due cioe naturale, et uiolente, et quegli trouai eſſer totalmente in accidenti contrarij mediante li lor contrarij effetti, ſimilmente trouai con ragione a l’intelletto euidente eſſer impoſſibile mouerſi un corpo graue di moto naturale et violente inſieme miſto Dapoi inueſtigai con ragione geometrice demoſtratiue la qualita di tranſiti, ouer moti uiolenti de detti corpi graui, ſecondo li uarij modi che pono eſſer eietti, ouer tirati uiolentemente per aere. Oltra di queſto me certificai con ragioni geometrice demoſtratiue. Qualmente tutti li tiri de ogni ſorte artegliarie, ſi grande come piccole egualmente elleuate ſopra il pian de l’orizonte, ouer egualmente oblique, ouer per il pian de l’orizonte, eſſer fra loro ſimili et conſequentemente proportionali, et ſimilmente le distantie loro. Dapoi conobbi con ragion naturale qualmente la diſtantia del ſopra detto tiro elleuato alli 45 gradi ſopra a l’orizonte, era circa decupla al tramito retto dun tiro fatto per il piano de l’orizonte, che da bombardieri è detto tirar de ponto in bianco, con la qual euidentia Magnanimo Duca trouai con ragioni geometrice et algebratice qualmente una balla tirata uerſo li detti 45 gradi ſopra a l’orizonte ua circa a quattro uolte tanto per linea retta di quello che ua eſſendo tirata per il pian de l’orizonte che da bombardieri è chiamato (come ho detto) tirar de ponto in bianco. Per il che ſi manifeſta qualmente una balla tirata da una medema artegliaria ua piu per linea retta per un uerſo che per un’altro, et conſequentemente fa maggior effetto. |

that according to the ratio of the first [shot], the second [shot] (that is, the one that was shot two points lower[)] was shot farther or that according to the ratio of the second [shot] the first one was shot less far, as you will soon know and see in the fourth book (where we will speak about the ratios among the shots). Your Magnanimity should also know that, as I had entered [the investigation of] this matter by that time, I decided to investigate9 further. I started (not without reason) to investigate the kinds of motions that take place when a heavy body is involved. I found that there are two kinds [of motion]:10 the natural and the violent. I also found that, in reference to their accidents,11 they are completely contrary to each other because of their contrary effects. Similarly, with an argument evident to the intellect, I found it is impossible for a heavy body to move according to natural and violent motion mixed together. Then12 by means of geometrical and demonstrative arguments, I investigated the qualities of the transits, that is, of the violent movements of the mentioned heavy bodies in reference to the different ways in which they can be projected or violently thrown through the air. Besides this, using geometric and demonstrative arguments, I certified that all the shots of all kinds of artillery, large as well as small and equally elevated above the horizon or equally oblique13 or parallel to the plane of the horizon, are similar to each other and consequently also proportional to each other. Similarly, [the same is true] for their ranges. Then,14 using natural arguments,15 I found that the range of the above-mentioned shot elevated at 45 degrees above the horizon was ten times the straight transit of a shot made parallel to the plane of the horizon, which is said by the bombardiers shooting at the blank point. On the basis of this evidence, Magnanimous Duke, using means of geometric and algebraic arguments, I found that a ball thrown along the mentioned 45 degrees above the horizon moves along a straight line which is about four times the straight line along which a ball moves when thrown parallel to the plane of the horizon, called by the bombardiers (as I said) shooting at the blank point. From this, it also becomes clear16 that a ball thrown by the same artillery follows a longer straight line in a certain way than in others and, consequently, produce more [destructive] effect. |

|

EPISTOLA - Terzo folio (non numerato), verso - cont. |

EPISTLE - Third folio (unnumbered), verso - cont. |

|

|

Anchor Signor Illustriſsimo calculando trouai la proportion, dil creſcere e calar che fa ogni pezzo de artegliaria (nelli ſuoi tiri) alzandolo ouer arbaſſandolo ſopra il pian de l’orizonte, et ſimilmente trouai il modo di ſaper trouar la uarieta de detti tiri in cadaun pezzo ſi grande come piccolo mediante la notitia d’un tiro ſolo (domente che ſempre ſia egualmente cargato) Dapoi inueſtigai, la proportione et l’ordini di tiri del mortaro, et ſimilmente trouai il modo di ſaper inuiſtigare ſotto breuita la uarieta de detti tiri pur per mezzo d’un tiro ſolo. Oltra di questo con ragioni euidentiſſime conobbi qualmente un pezzo de artegliaria poſſeua per due diuerſe uie (ouer elleuationi) percottere in un medemo luoco, et trouai il modo di mandar tal coſa (accadendo) a eſſecutione (coſe non piu audite ne d’alcun’altro antico ne moderno cogitate) Ma dapoi conſiderai (Signor Magnifico) che tutte queste coſe erano di puoco giouamento a un bombardiero quando che la diſtantia dil luoco doue gli occoreſſe di battere non gli fuſſe nota. Eſſempi gratia occorrendogli a tirare in un luoco apparente che la distantia di quello gli fuſſe occulta Che gli giouaria (O Magnanimo Duca) in questo caſo che lui ſapeſſe che il ſuo pezzo tiraſſe alla tal elleuatione paſſa 1356 et alla tal altra paſſa 1468, et alla tal altra paſſa 1574 et coſi diſcorrendo de grado in grado, certo nulla li giouaria, perche non ſapendo la distantia |

Moreover, Most Illustrious Lord, I found by means of calculations the proportion according to which the [ranges of] the shots of each piece of artillery increase and decrease when the piece is elevated or lowered above the plane of the horizon. Similarly,17 I also found the method of how to ascertain18 the characteristics of the mentioned shots in each piece, both large and small, solely on the basis of the information concerning one single shot (provided the piece is always charged in the same manner). Then,19 I investigated the proportions and characteristics of the shots of the mortar and, similarly, I found the method of how to ascertain the characteristics of the mentioned shots in a short time on the basis of the information concerning one single shot. Besides this, I found with a very evident argument that a piece of artillery can hit one place along two different paths (or at two different elevations) and I found the method of how to execute this in reality (a subject never heard20 or conceived by anyone else, ancient or modern). But then I realized that all these subjects (Magnificent Lord) are not really useful to the bombardier if he does not know the distance to the place he needs to strike. For example, if he needs to shoot at a place at a distance that is unknown, how could he make use (Magnanimous Duke) of the knowledge that allows him to shoot at 1356 steps if his piece is set at a certain elevation, or at 1468 steps at another elevation, or at 1574 at another elevation again, and so on, degree upon degree? It would not be at all useful because, unless he knows the distance, he will |

|

EPISTOLA - Quarto folio (non numerato), recto |

EPISTLE - Fourth folio (unnumbered), recto |

|

|

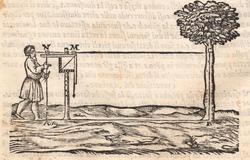

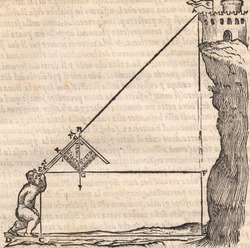

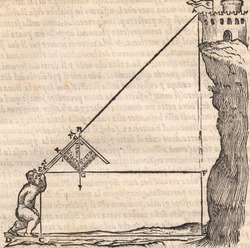

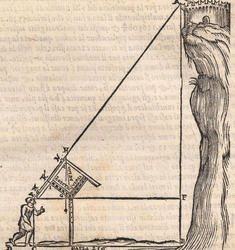

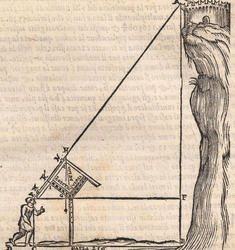

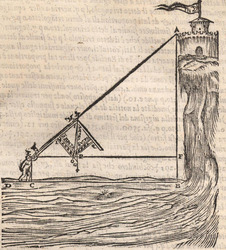

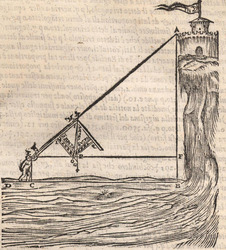

manco ſapra a che ſegno, ouer elleuatione debba aſſettar tal ſuo pezzo de artegliaria che percotta nel deſiderato loco, Seguita adonque due eſſer le principal parti neceſſarie a un real bombardiero (uolendo tirar con ragione et non a caſo) delle quale l’una ſenza l’altra quaſi niente gioua (Dico nelli tiri lontani) La prima è che groſſo modo ſappia conoſcere et inuestigare (con l’aſpetto) la distantia dil luoco doue gli occorre de tirare. La ſeconda è che ſappia la quantita di tiri della ſua artegliaria, ſecondo le ſue uarie elleuationi, le qual coſe ſapendo non errara de molto nelli ſuoi tiri ma mancandoui una di quelle non puo tirar (in conto alcuno) con ragione ma ſolamemte a diſcretione et ſe per caſo percotte al primo colpo nel luoco, ouer apreſſo al luoco doue deſidera, è piu presto per ſorte che per ſcientia (dico pur nelli tiri lontani) Perilche (Signor Illuſtrißimo) trouai un nouo modo da inuestigar ſotto breuita le altezze, profondità, larghezze, diſtantie ypothumiſſale, ouer diametrale, et ancora le orizontale delle coſe apparente, non in tutto come coſa noua, Perche in uero Euclide nella ſua perſpettiua ſotto breuita theoricamente in parte ne linſegna, ſimilmemte Giouanne Stoflerino, Orontio, Pietro Lombardo. et molti altri hanno datto a tal materie norma, chi con il ſole, chi con un ſpecchio, chi con il quadrante, chi con lo astrolabio, chi con due uirgule, chi con un baſtone (intitolato baculo de Iacob) et in molti altri uarij modi, Ma io dico (Signor Clarißimo) che trouai un nouo modo iſpidiente e preſto et facile da capire a cadauno (et a men errori ſuggetto de qualunque altro) da inuestigare le dette distantie, il quale da niun altro è ſtato poſto maßime delle diſtantie ypothumiſſale ouer diametrale ancora delle orizontale, le quale inuero ſono le piu neceſſarie al bombardiero de tutte le altre ſorte di dimenſioni, perche a quello non è molto neceſſario a ſapere la altezza duna coſa perpendicolarmente elleuata ſopra al orizonte, ne anchora la profondita duna coſa profunda, ne anchora la larghezza duna coſa lata, Ma ſolamente le dette distantie ypothumiſſale, et orizontale gli ſono molto al propoſito, come nel quarto libro (a uostra Illustrißima Signoria) ſi fara manifesto. |

not know at which point or elevation he has to set his piece of artillery so as to strike the place he desires. Therefore there are two21 fundamental subjects necessary to the real bombardier (if he does not want to shoot casually, but with cognition) and one subject without the other is not really useful (I say this concerning long shots).22 The first thing is that he has to be able to find out and investigate (by sight) the distance to the place he needs to shoot.23 The second is that he needs to know the quantities24 of the shots of his artillery according to the various elevations. If he knows both of these subjects, he will not make any major mistakes while shooting, but if one of these subjects is missing, he cannot shoot with cognition in any way but subjectively, and if he casually strikes the place he would like to strike, or if he strikes close to that place, this would be through luck rather than science (I repeat that this concerns long shots). For this reason, Very Illustrious Lord, I found a new method to measure in a short time the heights, depths, widths,25 diametral distances, or hypotenuses, and also the horizontal [heights] of the perceptible objects, though it is not a completely new subject. Euclid briefly explains the theory of parts of this subject in his Perspective. Similarly, Giovanne Stoflerino,26 Orontio,27 Pietro Lombardo and many others have standardized this subject. Someone used the Sun, others a mirror, a quadrant, an astrolabe or two rods, someone also used a stick (called a Jacob’s staff) and many other means were also used. But I say (Most Illustrious Lord) that I have found a new and fast method, easily understandable to everyone (and less subject to mistakes than any other method), to measure the mentioned distances. This method has not been suggested by anyone else, especially concerning the diametral distances or hypotenuses and horizontal distances. These measurements are indeed more essential28 to the bombardier than any other kind of measurement, because to him it is not particularly useful to know the height of an object elevated perpendicularly to the horizon, the depth of a low object or the width of a wide object. Particularly useful to him are only the hypotenusal and horizontal distances, as will be manifested (to the Most Illustrious Lordship) in the fourth book. |

|

EPISTOLA - Quarto folio (non numerato), recto - cont. |

EPISTLE - Fourth folio (unnumbered), recto - cont. |

|

|

Oltra di queſto per curioſita, me meſſe a ſcorrere li uarij modi oſſeruato da noſtri antiqui Naturali, et anchor da moderni nelle compoſitioni de fuochi et fra naturali inueſtigai la natura di quelle gumme, bitumi, graſſi, olei, ſali, acque ſtillate, et altri ſimplici minerali, et non minerali dalla natura prodotti, et da l’arte fabricati, componenti quelli, et conſequentemente trouai il modo di componere molte altre uarie et diuerſe ſpecie de fuochi non ſolamente alla diffenſione de ogni murata terra utilißimi, ma anchora in molte altre occurrentie molto al propoſito. Per le qual coſe haueua deliberato de regolar l’arte de bombardieri, et tirarla a quella ſottilita, che fuſſe poßibile de tirare (mediante alcune particolar iſperientie) perche in uero (come dice Ariſtotile nel ſettimo della Phyſica teſto uigeſimo) dalla iſperientia di particolari pigliamo la ſcientia uniuerſale. Ma poi fra me penſando un giorno, mi parue coſe biaſmeuole, uituperoſa, e crudele, et degna di non puoca punitione apreſſo a Iddio, et alli huomini a uoler studiare di aſſotigliare tal eſſercitio dannoſo al proßimo, anzi destruttore della ſpecie humana, et maßime de Chriſtiani in lor continue guerre. Perilche non ſolamente poſpoſi totalmente il studio di tal materia et atteſi a ſtudiar in altro, ma anchor ſtrazai, et abruſciai ogni calculatione, et ſcrittura da me |

Besides this and out of curiosity, I began to read the various methods, observed by our ancient ancestors and also by the moderns, to compound fires. Among the natural [subjects] I investigated the nature of those gums, bitumens, greases, oils, salts, distilled waters and other simple and not simple minerals, of which the above-mentioned things are constituted and that are produced by nature and manufactured by art. Consequently, I found the way to compound many other and different kinds of fires that are very useful not only for defending fortified land, but also for many other occasions.29 I had deliberated regulating the art of the bombardiers and achieving the perfection that can be achieved (by means of certain particular experiments) because (as Aristotle says in the seventh [book] of Physics, twentieth text), we reach universal science through the experience of the particulars. One day, however, I was thinking to myself30 and it seemed to me that working toward the perfection of such an art, harmful to the neighbor or even destructive for the human species and especially for the Christians because of their continuous wars, was a reproachful, vituperative and cruel thing, worthy of heavy punishment by God and by human beings.31 For this reason,32 not only did I completely postpone the investigation of such matters and begin to work on another subject, I also shredded and burned all the calculations and writings that I had |

|

EPISTOLA - Quarto folio (non numerato), verso |

EPISTLE - Fourth folio (unnumbered), verso |

|

|

notata, che di tal materia parlaſſe. Et molto mi dolſl, et auergognai del tempo circa a tal coſa ſpeſſo, et quelle particolarita, che nella memoria mi restorno (contra mia uolunta) iſcritte mai ho uoluto paleſarle ad alcuno, ne per amicitia, ne per premio (quantunque ſia ſtato da molti richieſto) perche inſignandole mi parea di far naufragio, e grande errore. Ma hor uedendo il luppo deſideroſo de intrar nel noſtro armento, et accordato inſieme alla diffeſa ogni noſtro pastore non mi par licito al preſente di tenere tal coſe occulte, anci ho deliberato di publicarle parte in ſcritto, et parte uiua uoce a ogni christiano, accioche cadauno ſia meglio atto ſi nel offendere, come nel diffenderſi da quello. Et molto mi doglio uedendo il biſogno che tal studio all’ora abandonai, perche ſon certo che hauendo ſeguito fin hora harei trouato coſe di maggior ualore come ſpero in breue anchora di trouare. Ma perche il preſente è ſcerto (e al tempo breue) il futuro è dubioſo uoglio iſpedire prima quello che al presente mi trouo, et per mandar tal coſa imparte a eſſecutione ho composto impreßia la preſente operina la quale ſi come ogni fiume naturalmente cerca di accoſtarſe, et unirſe col mare, coſi eſſa [(]conoſcendo uoſtra Illust. D. S. eſſer la ſomma fra mortali de ogni bellica uirtu) recerca di accostarſe, et unirſe con eſſa amplitudine. Pero ſi come lo abondante mare, il quale non ha di acqua biſogno non ſe ſdegna di receuer un picol fiume, coſi ſpero che uoſtra D. S. non ſe ſdegnara di acettarla, accioche li peritiſſimi bombardieri di questo noſtro Illuſtriſſimo Dominio ſugetti a uoſtra Sublimita, oltra il ſuo ottimo, et pratical ingegno, ſiano meglio di ragion iſtrutti, et atti a eſſeguire li mandati di quella. Et ſe in queſti tre libri non ſatisfaccio plenariamente uostra Eccellentiſſima Signoria inſieme con li predetti ſuoi peretiſſimi bombardieri, ſpero in breue con la pratica del quarto et quinto libro non gia in stampa (per piu riſpetti) ma ben a pena, ouer uiua uoce di ſadisfar in parte uoſtra Sublimita inſieme con quegli alla cui gratia da Infimo, et humiliſſimo Seruitore Diuotamente mi raccomando. Data in Venetia in le caſe noue di San Saluatore alli XX di Decembrio MDXXXVII. De uoſtra Illustriſſima D.S. Infimo Seruitore. Nicolo Tartaglia Briſciano. |

annotated concerning such matters. I was very upset and ashamed about the time I had spent [working on] this subject. Also, I did not want to tell anyone of those particular things that remained on my mind (against my will), neither because of friendship nor reward (though I was asked by many people to do so) and this was because, had I taught them, it seemed to me that I would be making a big mistake. But now, as I see the wolf33 wishing to join our flock and since each shepherd agrees with the need for defense, it does not seem licit to me to keep these things hidden and I have deliberated published them, partly in written form and partly viva voce with every Christian, so that everyone is better prepared to both attack [the wolf] and to defend himself. I now deeply regret34 abandoning such an investigation at that time, now that such knowledge is so necessary, and I am sure that had I continued I would have disclosed even more relevant subjects, as I hope to do in the near future. However, as the present is certain35 and the future is uncertain, I want to make public first what I have at disposal now. To realize this idea, at least partially, I quickly prepared the present short work. Just as all rivers tend naturally to get closer and join the sea, this short work tries to get closer and join You, as Your Illustrious Ducal Lordship is the sum, among mortals, of every virtue of war. Therefore, like the abundant sea that, though it needs no more water, nevertheless does not disdain from accepting a small river, I hope that Your Ducal Lordship does not disdain from accepting this work. In this way, the very skilled bombardiers of this our very illustrious Dominion, subject to Your Sublimity, besides being instructed by Your excellent and practical wisdom, will be better instructed also by the intellect and thus, better able to execute your orders. If, by means of these three books, I do not entirely satisfy Your Most Excellent Lordship and your mentioned very skilled bombardiers, I do hope that I will partly satisfy Your Sublimity and the others with the instructions contained in the fourth and fifth book, which are not yet in print (because of several reasons) but only handwritten, or by viva voce. As a small and humble servant, I devotedly recommend myself to You. Delivered in Venice at the new house of San Salvatore on the 20th of December 1537. Lowest Servant of Your Most Illustrious Ducal Lordship. Nicolo Tartaglia from Brescia. |

|

LIBRO PRIMO - 1r |

FIRST BOOK - 1r |

|

|

First Book COMINCIA IL PRIMO LIBRO DELLA NOVA SCIENTIA DI NICOLO TARTAGLIA BRISCIANO, dalle diffinitioni, ouer dalle deſcriptioni delli principij, per ſe noti delle coſe premeſſe. DIFFINITIONE PRIMA. Corpo egualmente graue è detto quello, che ſecondo la grauita della materia, et la figura di quella è atto à non patire ſenſibilmente la oppoſition di l’aere in alcun ſuo moto. OGNI corpo (come uoleno li naturali) ò che egli ſemplice ò che egliè compoſto, li ſemplici ſono cinque, cioe, terra, acqua, aere, fuoco, et cielo. Tutti li altri dicono eſſer compoſiti dalli preditti, et queſti tali ſono li huomini, li animali, le piante, le pietre, li ſette mettalli. Et ogni altra ſpecie di corpo. Delli detti cinque corpi ſemplici, quattro ſono detti elementali, cioè la terra, lacqua, laere, e il fuoco, Laltro è chiamato quinta eſſentia, cioè il cielo. Delli detti quattro elementali (come uol Auicena in la ſeconda dottrina della prima fen del ſuo primo libro) dui ſono leui et dui graui. Li leui ſono il fuoco e laere. Li graui ſono la terra, et lacqua, ma Auerrois ſopra il quarto de celo et mundo (teſte 29) uol che tutti li detti corpi in li ſuoi luochi habbino alcuna grauita, eccetto che il fuoco, etiam alcuna leuita eccetto che la terra. Onde ſeguiria che laere nel proprio luoco participaſſe de grauita. Per ilche ſeguita che ogni corpo compoſto di 4 elementi in aere participa de grauita. Niente di meno per corpo egualmente graue in queſto luoco ſe intende ſolamente quello che ſecondo la grauita de la materia, et la forma di quella è atto a non patire ſenſibilmente la oppoſitione de laere in alcun ſuo moto. Secondo la materia, cioè che ſia di ferro, ouer di piombo, ouer di pietra, ouer di altra materia ſimile in grauita. Secondo la forma, cioe ch’l ſia unito di tal qualita, ch’l ſia atto a non patire ſenſibilmente (per uigor della forma) la detta oppoſition de l’aere in alcun ſuo moto. Onde fra le figure, ouer forme de corpi, la forma Cunea, ouer Pyramidale ſaria la prima, che ſaria piu atta a temere meno la detta oppoſition de laere de qual ſi uoglia altra forma, domente che con arte la fuſſe conſeruata |

THE FIRST BOOK OF THE NEW SCIENCE OF NICOLO TARTAGLIA FROM BRESCIA STARTS with the definitions, the descriptions of the principles, [which are] self evident as premises. FIRST DEFINITION. An equally heavy body is said to be a body which, according to the heaviness and shape of the matter, is not perceptibly influenced by air opposition during its motion. All bodies, as the Naturals say, are either simple or compounded. The simple bodies are five, that is, earth, water, air, fire and sky. All other bodies are said to be compounded of the mentioned simple ones. The compounded ones are humans, animals, plants, stones, the seven metals and every other kind of body. Four of the mentioned five simple bodies are said to be elementary, that is, earth, water, air and fire. The other body is called the fifth essence, that is, the sky. Of the four elementary elements (as is said by Avicenna in the second doctrine of the first Fen36 of his first book) two are light and two are heavy. The light ones are fire and air. The heavy ones are earth and water. However, in the fourth [book] of De caelo et mundo (text twenty-nine), Averroes states that all the mentioned bodies have in their places37 a certain gravity, except for fire, and a certain levity, except for earth. Consequently, air in its place has a certain gravity. From this follows that each body, compounded of four elements, one of which is air, shares gravity.38 Nevertheless, an equally heavy body is univocally understood in this work as the body that, in reference to the heaviness and shape of its matter, is not perceptibly influenced in each of its motions by the opposition of the air. Concerning the matter, [it can be] of iron, of lead, of stone or of another material similar in reference to its heaviness. Concerning the shape, this is characterized by such a quality that makes it appropriate to not be influenced (because of its shape) by the opposition of the air during all of its motions. Therefore, among the figures and shapes of the bodies, the wedge-shaped object, that is the pyramidal shape, is the most appropriate among all possible shapes in order [for it] not to be influenced by the mentioned air, provided that by means of a contrivance the body would remain |

|

LIBRO PRIMO - 1v |

FIRST BOOK - 1v |

|

|

che la uertice, ouer acutezza di quella ſempre procedeſſe auanti contra limpeto del detto aere. Ma per che ſe la non fuſſe conſeruata, come è detto, non ſegueria il propoſito, per non eſſer egualmente graue, Poremo la figura ouer forma ſpherica ſenzaltra conditione eſſer la piu atta a patire meno la detta oppoſitione de l’aere in ogni ſpecie di moto di qual ſi uoglia altra forma per eſſer piu agile al moto da tutte le bande, et egualmente graue de qual ſi uoglia altra. Diffinitione. II. Li corpi egualmente graui ſono detti ſimili et eguali quando che in quegli non é alcuna ſuſtantial ne accidental differentia. Diffinitione. III. Lo inſtante e quello che non ha parte. Lo inſtate in el tempo e in el moto e ſi come il ponto geometrico in le magnitudine, cioe chel non ha parte ma e indiuiſibile et conſequentemente non e tempo ne anchora mouimento, ma ben e principio e fine de ogni tempo, et dogni mouimento terminato. Et e proprio l’ultimo fine del tempo preterito, et non e parte del tempo futuro. Et è principio del tempo futuro et non è parte del tempo preterito come Ariſ. nel 6 della Phyſi. (teſto 24) ci manifeſta. Diffinitione. IIII. Il Tempo e una miſura del mouimento, et della quiete, li termini del quale ſon dui iſtanti. IL tempo da ſcientifici è ſtato in diuerſi modi diffinito, cioe alcuni dicono (come hauemo detto diſopra) que’leſſer una miſura del mouimento, Et della quiete. Altri determinan eſſer inducia del moto delle coſe uariabile. Alcuni conchiudano eſſer uiciſſitudine de coſe: le quale in molti modi per ſottil indagatione ſe cognoſcono. |

in a position so that its top would always proceed while remaining in front against the impetus of the mentioned air. If the object does not retain such a position, as has been said, it would not work properly as it would not be equally heavy.39 Without further investigation, we define the spherical figure or shape as the most appropriate among all possible shapes in order to avoid the mentioned opposition of the air in the frame of each kind of motion. This [spherical] shape is most appropriate for the motion on all of its sides and it is equally heavy on all of its sides as well. Second definition. Equally heavy bodies are said to be similar and equal when they do not show [among each other] any substantial or accidental differences. Third definition. The instant is that which does not have parts. The instant of time and of motion is like the geometrical point in the frame of magnitudes. It does not have parts and it is indivisible. Consequently, it is neither time nor motion but the beginning and end of each time and motion that are finite. It is the last end of the past time and this is not part of the future time. It is the beginning of the future time and this is not part of the past time, as Aristotle shows us in the sixth [book] of Physics (text twenty-four). Fourth definition. Time is a measure of motion and of the state of rest; its ends are two instants. Time has been defined by the scientific fellows in different ways. Certain [persons] say, as we have said above, that time is a measure of movement and rest. Others say it is the end of the motion of things that vary. Others conclude that it is the vicissitude of things and [such vicissitude] can be known in many ways by means of acute investigation. |

|

LIBRO PRIMO - 1v - cont. |

FIRST BOOK - 1v - cont. |

|

|

Et altri dicono eſſer una eta uolubile che preſto manca. Delle quali diffinitioni hauemo tolto la prima per eſſer piu accomodata al noſtro propoſito. Digando che il tempo è una miſura del mouimento, et della quiete: perche ſi come per mezzo de una miſura materiale (in piu terre chiamata perticha diuiſa in piedi 6. Et ciaſcun pie in once 12) ſe uiene in cognitione della longhezza, larghezza, et altezza di corpi materiali. Similmente per mezzo de una miſura di tempi (chiamata anno diuiſo in meſi 12 e ciaſcun meſe comunamente in giorni 30 e ciaſcun giorno in hore 24 e ciaſcuna hora in minuti 60) ſe conoſce la differentia di moti de corpi; cioe la uelocita. et tardita de quelli. Perche ſe conoſciuto in le ſette ſtelle erratice una eſſer di moto piu ueloce de l’altra? Se non per la miſura de eſſi mouimenti chiamata anno |

Others say it is an inconstant age that is soon missed. We have chosen the first of these definitions because it is more appropriate for our purpose. In the same way as the length, width and height of the material bodies can be known by means of a material unity of measurement (which is called perch in many countries and is divided into six feet and each foot into twelve inches), it is said that time is the measure of movement and of quiet. Similarly, by means of a unity of measurement for time (which is called year, divided into twelve months, and each month commonly [divided] into thirty days, each day into twenty-four hours and each hour into sixty minutes), the differences of the motions of the bodies can be known, that is, their velocity and slowness. How could it be known that one of the seven erratic stars has a faster motion than the others? By means of the measurement of their movements which is called year |

|

PRIMO LIBRO - 2r |

FIRST BOOK - 2r |

|

|

con le ſue parti (cioe meſi giorni hore e minuti) come chiaro appare in le determinationi Aſtronomatice. Et li termini di queſto anno, cioe il principio e fin di quello ſono dui iſtanti, il medemo ſi deue intendere in le altre ſue parti et in ogni altro tempo terminato. Diffinitione. V. Il mouimento dun corpo egualmente graue e quella tranſmutatione, che alle uolte fa da uno loco a un altro, li termini dil qual ſon dui iſtanti. Il mouimento da tutti li ſcientifici e maſſime da Ariſtotile nel quinto della Phyſica (teſto 9) è ſtato diffinito eſſer una mutatione, ouer traſmutatione. Ma le ſpecie di queſto mouimento, ouer traſmutatione alcuni uoleno che ſiano 6 cioe Generatione, Corrottione, Augmentatione, Diminutione, Alteratione, et mutation di luoco. Ma Ariſtotile in lo preallegato loco uole che le mutationi ſiano 3 e non piu, cioe mutation de quantita: de qualita, et ſecondo il luoco. Delle qual ſpecie hauemo tolto ſolamente la ultima (perche le altre non fanno al propoſito) dicendo, che il mouimento dun corpo egualmente graue e quella traſmutatione, che alle uolte fa da un luoco a uno altro, come ſaria a dir di ſuſo in giuſo, et di giuſo in ſuſo, di qua e di la dal’a banda deſtra alla ſiniſira et e conuerſo. Et li termini de tali mouimenti (cioe in principio e fin di quelli[)] ſono dui iſtanti. Diffinitione. VI. Mouimento naturale di corpi egualmente graui e quello che naturalmente fanno da un luogo ſuperiore a un’altro inferiore perpendicularmente ſenza uiolenza alcuna. Diffinitione. VII. Mouimento uiolente di corpi egualmente graui e quello che fanno sforzatamente di giuſo in ſuſo, di ſuſo in giuſo, di qua et di la, per cauſa di alcuna poſſanza mouente. Diffinitione. VIII. Li mouimenti de corpi egualmente graui, ſe dicono eguali quando che li detti corpi ſon ſimili, et uanno de egual uelocita |

with its parts (that is months, days, hours and minutes) as it clearly appears in the astronomical40 investigations. The ends of such a year, that is its beginning and end, are two instants. The same is true for all other parts of it and for all finite times. Fifth definition. The movement of an equally heavy body is the transmutation that it sometimes accomplishes from one place to the other, whose ends are two instants. All the scientific fellows and especially Aristotle in the fifth [book] of Physics (text nine) have defined movement as a mutation, that is, a transmutation. Someone counts six kinds of movements or transmutations: generation, corruption, augmentation, diminution, alteration and mutation of place. Aristotle, however, in the mentioned place defines the mutations as three and not one more: mutation of quantity, of quality and of place. From these sorts here we use only the last (because the others are not useful for our purpose) and we say that the movement of an equally heavy body is the transmutation, that it sometimes makes from one place to the other, as for instance downwards, upwards, from right to left and vice-versa. The end of such movements (that is their beginnings and their ends[)] are two instants. Sixth definition. The natural movement of equally heavy bodies is the movement they accomplish from a higher place to a lower one, perpendicularly and without any violence. Seventh definition. The violent movement of equally heavy bodies is the movement they accomplish with effort either upwards or downwards, to the right or the left, and is caused by a moving power. Eighth definition. The movements of equally heavy bodies are said to be equal when the mentioned bodies are similar and move with the same velocity, |

|

LIBRO PRIMO - 2v |

FIRST BOOK - 2v |

|

|

cioe che in tempi eguali tranſiſcono interualli eguali. Diffinitione. IX. Reſiſtente ſe chiama qualunque corpo manente, che per far reſiſtentia a un corpo egualmente graue in alcun ſuo moto uien da quello offeſo. Diffinitione. X. Reſiſtenti ſimili, ſe dicono quelli corpi, che reſtariano egualmente offeſi, da corpi ſimili egualmente graui, in mouimenti eguali, et in mouimenti ineguali inegualmente offeſi, cioè che quello, che faceſſe reſiſtentia al piu ueloce reſtaſſe piu offeſo. Diffinitione. XI. Lo effetto dun corpo egualmente graue ſe dice la offenſione, ouer percußione, ouer il bucco che in ogni moto cauſa in un reſiſtente. Diffinitione XII. Et quando le percussioni, ouer bucchi de corpi ſimili egualmente graui, ſono eguali, ſe dicono effetti eguali, et ſe ineguali, ineguali effetti. Diffinitione. XIII. Poſſanza mouente uien detta qualunque artificial machina, ouer materia, che ſia atta a ſpingere, ouer tirare un corpo egualmente graue uiolentemente per aere. Diffinitione. XIV. Le poſſanze mouente, uengono dette ſimile et eguale quando che in quelle non é alcuna ſuſtantia ne accidental differentia nel ſpinger de corpi egualmente graui ſimili et eguali, |

that is, they move along equal intervals in equal times. Ninth definition. A body that is at rest and opposes resistance to an equally heavy body during its motion and is damaged by the latter is called resistant. Tenth definition. Those bodies that are damaged in the same way by similar equally heavy bodies during equal movements are called similar resistants. If the movements are unequal, they are unequally damaged so that the body that is damaged by the faster one is damaged more. Eleventh definition. The effect of an equally heavy body is called damage or percussion or the hole that is caused in each resistant during each motion. Twelfth definition. When the percussions or holes of similar equally heavy bodies are equal, the effects are said to be equal. If they are unequal, the effects are unequal. Thirteenth definition. The moving power is said to be any artificial machine or matter that is able to push or throw an equally heavy body violently through the air. Fourteenth definition. The moving powers are said to be similar and equal when there is no substantial or accidental difference [in their motions] while pushing equally heavy bodies which are similar and equal. |

|

LIBRO PRIMO - 3r |

FIRST BOOK - 3r |

|

|

Ma quando in quelle e alcuna accidental differentia ſono dette dißimile, et ineguale. Suppoſitione prima. El ſe ſuppone che il corpo egualmente graue (in ogni mouimento) uada piu ueloce doue fa, ouer faria (per comuna ſententia) maggior effetto in un reſiſtente. Suppoſitione. II. El ſe ſuppone che dui corpi egualmente graui ſimili et eguali, habbino tranſito, ouer che trapaſſeranno in tempi eguali ſpacij eguali terminanti in dui iſtanti, doue detti corpi paſſerebbono di egual uelocita. Suppoſitione. III. Et ſe ſuppone doue che corpi egualmente graui ſimili et eguali, fariano (per commune ſententia) eguali effetti in reſiſtenti ſimili, paſſerebbono per tai iſtanti, ouer luochi de egual uelocita. Suppoſitione. IIII. Ma doue fariano ineguali effetti ſe ſuppone, che quelli paſſerebbono de ineguali uelocita, et che quello, che faria maggior effetto paſſeria piu ueloce. Suppoſitione V. Li effetti de corpi egualmente graui ſimili et eguali fatti nelli ultimi iſtanti di lor moti uiolenti in reſiſtenti ſimili |

But if there is some substantial or accidental difference they are called dissimilar and unequal. First supposition. It is supposed that an equally heavy body (during each motion) moves faster when it produces or would produce (for common judgement) a greater effect against a resistant. Second supposition. It is supposed that two equally heavy bodies similar and equal to each other have the [same] transit, that is, they cover equal spaces in equal times that end with two instants, if the mentioned bodies move with the same velocity. Third supposition. It is supposed that if two equal and similar equally heavy bodies produce (for common judgement) equal effects in similar resistants, they go through the same instants, that is, places with the same velocity. Fourth supposition. But if they produce unequal effects, it is supposed that they go through unequal velocities and the one that produces the greater effect goes through faster. Fifth supposition. The effects produced in similar resistants by equally heavy bodies, which are equal and similar to each other during the last instants of their violent motions, |

|

LIBRO PRIMO - 3v |

FIRST BOOK - 3v |

|

|

ſe ſuppongono eſſer eguali. Comune ſententie. Prima Quanto piu un corpo egualmente graue uera da grande altezza di moto naturale, tanto maggior effetto fara in un reſiſtente. Seconda. Se corpi egualmente graui ſimili et eguali ueranno da egual altezza ſopra a reſiſtenti ſimili di moto naturale faranno in quegli eguali effetti. Terza. Ma ſe uerranno da ineguale altezza, faranno in quegli ineguali effetti, et quello che uera da maggior altezza fara maggior effetto. Ma biſogna notare che le dette altezze ſi deueno intendere reſpetto alli reſiſtenti. Quarta. Se un corpo egualmente graue nel moto uiolento trouara alcun reſiſtente, quanto piu el detto reſiſtente ſara propinquo al principio di tal moto, tanto maggior effetto fara il detto corpo in lui. Propoſitione. Prima. Ogni corpo egualmente graue nel moto naturale, quanto piu el ſe andara aluntanando dal ſuo principio, ouer appropinquando al ſuo fine, tanto piu andara veloce. |

are supposed to be equal. First common sentence.41 The greater the height from which an equally heavy body descends in natural motion, the greater the effect it produces on a resistant.42 Second [common sentence]. If equally heavy bodies, similar and equal to each other, descend from an equal height on similar resistants in natural motion, they produce equal effects on them. Third [common sentence]. But, if they descend from unequal heights, they produce unequal effects and the one that descends from a greater height produces a greater effect. One has to note, however, that the mentioned heights have to be conceived in respect of [the position] of the resistants. Fourth [common sentence]. If an equally heavy body finds a resistant along its violent motion, the closer the resistant is to the beginning of the motion, the greater the effect is that the mentioned body produces on it. First proposition. The farther each equally heavy body goes along its natural motion from its beginning, or the closer it comes to its end, the faster it travels. |

|

LIBRO PRIMO - 4r |

FIRST BOOK - 4r |

|

|

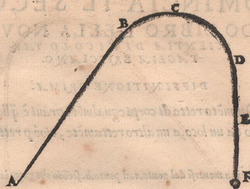

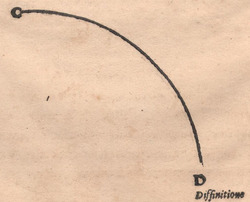

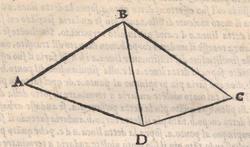

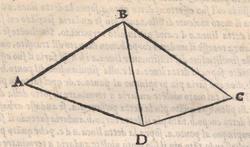

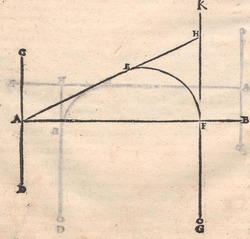

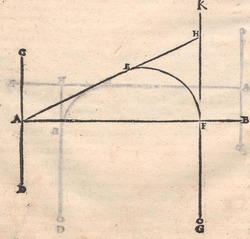

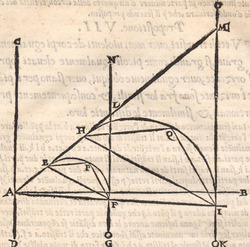

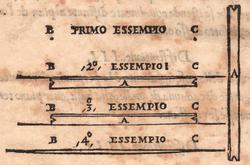

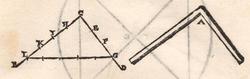

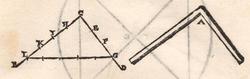

Esſempio ſel fuſſe le 3 diuerſe altezze A B C in retta linea, come di ſotto appare, et che dalla altezza A per caſo caſcaſſe da ſe vn corpo egualmente graue, ſenza dubbio quello tal corpo, non trouando reſiſtentia andaria di moto naturale ſin in terra facendo il viazzo ſuo alla ſimilitudine de la linea DEFG hor dico che il moviment[o] di quello tal corpo ſaria di tal conditione che quanto piu el ſe andaſſe aluntanando dal ſuo principio (cioe da lo iſtante, ouer ponto D) ouer appropinquando al ſuo fine (cioe allo iſtante, ouer ponto G[)] tanto piu andaria ueloce. Perche il detto corpo in tal mouimento (per la prima comuna ſententia) faria maggior effetto in vn reſiſtente, il qual fuſſe fuor dalla altezza A43 che dalla altezza B. Seguitaria adunque, che il detto corpo (per la prima ſuppoſitione) andaria piu ueloce per lo ſpacio EF che per lo ſpacio DE. Similmente perche lo detto corpo (per la detta prima comuna ſententia) faria maggior effetto in un reſiſtente, che fuſſe nel ponto G, che ſel fuſſe alla altezza C. Seguiria adoncha (per la medema prima ſuppoſitione) che lo detto corpo andaria piu veloce per lo ſpacio FG che per lo ſpacio EF et ſe paſſar poteſſe il ponto G cioè che la terra gli andaſſe cedendo loco, como fa l’aere andaria continuamente augumentando in uelocita, fin al centro dil mondo poi in eſſo centro ſe ripoſaria (per comuna sententia de Philoſophi) ſi che quando lo detto corpo fuſſe propinquo al detto centro, ueria a eſſer di moto piu uelociſſimo, che in alcun paſſato ſpacio fuſſe stato che é il propoſito. Queſto medemo ſe uerifica ancora in cadauno che vada uerſo un loco deſiato che quanto piu ſe ua approßimando al deto loco, tanto piu ſe ua allegrando, e piu ſe sforza di caminare, como appar in un peregrino, che uenga dalcun luoco luntano che quando è propinquo al ſuo paeſe, ſe sforza naturalmente al caminar a piu potere tanto piu quanto piu uien di lontan paeſi pero il corpo graue fa il medemo andando uerſo il ſuo proprio nido, che è il centro dil mondo, et quando piu vien di lontano in eſſo centro, tanto piu (giongendo a quello) andaria veloce. ANcor che la opinione de molti ſia che ſel fuſſe un forame che penetraſſe diametralmente tutta la terra, et che per quello fuſſe laſſato andar un corpo egualmente graue, come diſopra e ſtato detto, che quel tal corpo gionto che fuſſe al centro del mondo immediate iui ſe fermaria, la qual openione, dico non eſſer uera che coſi immediate che ui fuſſe agionto ui ſe gli fermaſſe, |

For example, let there be three different heights A, B, C along a straight line, as it appears below. Casually, an equally heavy body falls down from the height A. That body, as it does not find any resistance, certainly moves along a natural motion down to the bottom and travels in a way similar to the line DEFG. I say that the movement of that body has that characteristic according to which the farther it moves away from its beginning (that is, from the instant or point D), or the closer it comes to its end (that is, to the instant or point G[)], the faster it goes. This occurs because the mentioned body that moves with such a motion (because of the first common sentence) produces a greater effect on a resistant if it falls from height A44 than from height B. It follows from the foregoing that the mentioned body45 (because of the first supposition) travels faster along space EF than along space DE. Similarly, as the mentioned body (because of the mentioned first sentence) produces a greater effect on a resistant at point G than if it were at [the point of] height C, it follows that (because of the same first supposition) the mentioned body travels faster along space FG than along space EF. If it could then travel beyond point G, that is, if the earth gave free space to it as the air does, it would continuously increase its velocity until [it reaches] the center of the Earth. Then it would rest at that center (according to the common judgement of the Philosophers). Thus, when the mentioned body is close to the mentioned center, it has [reached] a faster motion than in any other space through which it has traveled before, which was to be demonstrated. The same happens each time one moves toward the place that one aspires to, and the closer one comes to that place, the happier one is and the more effort one puts into walking fast. It appears to be similar for the pilgrim who comes from a distant place and who is approaching his village. The closer he gets, the greater effort he naturally makes to walk in the fastest way possible, and the faster he goes, the more distant the place is from which he came. The heavy body behaves in the same way when it moves toward its nest, that is, the center of the world: the farther it moves from that center from which it came, the faster it travels (the closer it gets to it).46 It is the opinion of many that if a hole diametrically penetrated the entire Earth and if an equally heavy body was allowed to travel through that hole, as has been said above, the mentioned body would immediately rest as soon as it reached the center of the world. I claim that the opinion that it would stop immediately when it arrived there is not true. |

|

LIBRO PRIMO - 4r - cont. |

FIRST BOOK - 4r - cont. |

|

|

anci per la grande uelocita che in quello ſi trouaſſe ſaria sforzato a paßare di moto uiolente molto, e molto oltra il detto centro ſcorendo uerſo il cielo del noſtro ſubterraneo emiſperio, da poi retornaria di moto naturale uerſo il medemo centro, et gionto a quello lo paßaria ancor per le medeſime ragioni di moto uiolente uerſo di noi, Et pur di nouo retornaria pur di moto naturale uerſo il medeſimo centro, et pur di nouo lo paßaria di moto uiolente, et da poi retornaria di moto naturale, et coſi andaria un tempo paſſando di moto uiolente, et ritornando di moto naturale ſminuendoſi continuamente in lui la uelocita, et finalmente ſe fermaria poi nel detto centro. Per il che egliè coſa manifeſta che dal moto naturale ſi cauſa il uiolente, et non è conuerſo, cioe che dal uiolente giamai uien cauſato il naturale, anci ſi cauſa per ſe. |

Because of the great velocity that it has at that [point], it would be forced to go through [the hole] according to its violent motion for longer and longer [space] beyond the mentioned center and toward the sky of the hemisphere beneath us. It would then move back along a natural motion toward the same center, and once it arrived would pass it again for the same reason, but along a violent motion toward us. And again it would move back along a natural motion toward the same center and again would pass it due to the violent motion. In this way, a certain time would elapse during which it would pass [the center] with its violent motion and then come back because of its natural motion, continuously decreasing its velocity and, finally, coming to rest at the mentioned center. Therefore, it is evident that the violent motion is caused by the natural one, but not the opposite. That is, the natural motion is never caused by the violent one. This is caused by itself. |

|

LIBRO PRIMO - 4v |

FIRST BOOK - 4v |

|

Correlario Primo. Onde el ſi manifeſta ancora qualmente ogni corpo egualmente graue in el principio del mouimento naturale ua piu tardißimo, et in fin piu uelocißimo che in ogni altro luoco, et quanto piu paſſera per longo ſpacio tanto piu in fine andara uelocißimo. Correlario. II. Anchora è manifeſto qualmente un corpo egualmente graue di moto naturale non puo paſſare per dui diuerſi iſtanti |

First corollary. It is therefore manifest that every equally heavy body travels slowest at the beginning of its natural motion and is faster at the end [of its motion] than at any other place, and the longer the space is that it has traveled, the faster it is at the end. Second corollary. It is also manifest that an equally heavy body [moving] with natural motion cannot pass through two different instants with |

|

LIBRO PRIMO - 5r |

FIRST BOOK - 5r |

|

|

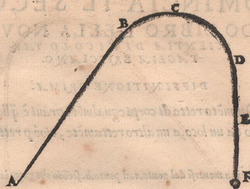

di egual uelocita. Propoſitione. II. Tutti li corpi egualmente graui ſimili, et eguali dal principio delli lor mouimenti naturali, ſe partiranno de egual uelocita, ma giongendo al fine di tali lor mouimenti, quello che hauera paſſato per piu longo ſpacio andara piu ueloce. SEl fuſſe le quatro diuerſe altezze A, B et C, D poſte a due a due in retta linea come diſotto appare, et che la altezza A fuſſe tanto lontana dalla

|

the same velocity. Second proposition. If all equally heavy bodies, similar and equal to each other at the beginning of their natural motions, start [moving] with the same velocity, when they arrive at the end of their movements, the one that has passed a longer space will have traveled faster. Let the four different heights A, B and C, D be placed in twos on a straight line as it appears below, and let height A be as far from

|

|

LIBRO PRIMO - 5v |

FIRST BOOK - 5v |

|

|

altezza B quanto è la altezza C dalla altezza D et che per caſo dalla altezza A47 caſcaſſe un corpo egualmente graue, et un’altro ne caſcaſſe dall’altra altezza C li quai corpi fuſſeno ſimili, et eguali. Le noto che quegli tai corpi andariano di moto naturale in terra, et li tranſiti loro ſariano retti e perpendicolari alla terra cioe alla ſimilitudine delle due linee GF et IE. Hor dico che queſti tai corpi ſe partiriano dal ſuo principio (cioe l’uno dallo iſtante, ouer ponto G et l’altro dallo iſtante ouer ponto I) de egual uelocita, ma giongendo al fine di tali mouimenti, cioe alli dui iſtanti E et F quello che ueniſſe dalla altezza A andaria piu veloce di l’altro perche quello haueria tra[n]ſito per piu longo ſpacio el quale è il ſpacio AF. Perche l’altezza B é tanto lontana dalla altezza A quanto che è l’altezza D dall’altezza C (dal proſupoſito) adonque il corpo: che cadeße dalla altezza A percottendo in uno reſiſtente, che fuße fuora dalla altezza B el non faria in quello maggior effetto (per la ſeconda comuna ſententia) di quello che faria quello, chi cadeße dalla altezza C ſopra dun’altro ſimile che fuße fuora della altezza d[’]onde (per la terza ſuppoſitione) li detti dui corpi andaranno l’uno per l’altezza B in ponto H et l’altro per l’altezza D in ponto K de egual uelocita. dil che (per la ſeconda ſuppoſitione) li detti dui corpi andarrano l’uno il ſpacio GH et l’altro il ſpacio IK in tempi eguali. Adonque li detti dui corpi ſe partiriano dal principio de lor mouimenti (cioè l’uno da lo istante G et l’altro da lo iſtante I) de egual uelocita che é il primo propoſito. Et perche il corpo, che ueniße dall’altezza A faria maggior effetto in un reſiſtente, che fuße in lo iſtante F (per la terza comuna ſententia) di quello che faria quello che ueniße dalla altezza C in un’altro ſimile chi fuße in ponto E. Onde (per la prima ſuppoſitione) lo detto corpo che uerria dall’altezza A giongendo al fin dil ſuo mouimento (cioé allo iſtante, ouer ponto F) andaria piu ueloce di quello che uerria dall’altezza C giongendo al ſuo fine, cioè allo iſtante, ouer ponto E che è il ſecondo propoſito. A dimoſtrar el medemo ſecondo propoſito per un altro modo: de tutta la linea, ouer tranſito GF maggiore, ne tagliaremo (per la terza del primo de Euclide) la parte GM egual al tranſito, ouer linea IE minore et perche tutti li corpi egualmente graui ſimili, et eguali dal principio delli loro mouimenti naturali ſe parteno de egual uelocita (come di ſopra fu dimonstrato) lo corpo adonque che ſe parteße dall’altezza A andaria tanto ueloce per lo ſpacio GM quanto faria quello che ſe partiße dall’altezza C per lo ſpacio IE cioé ambi doi tranſiriano in tempi eguali. |

height B as height C is from height D. Let an equally heavy body casually fall from height A48 and another one from the other height C; these bodies are similar and equal [to each other]. I point to the fact that those bodies would move toward the ground with a natural motion and their transits would be straight and perpendicular to the ground, as lines GF and IE show. I claim that these two bodies start off from their beginning (that is, one from the instant or point G and the other from the instant or point I) with equal velocities. Then, when they come to the end of their movements, that is, at the two instants E and F, the one that comes from the height A moves faster than the other because it has transited a longer space, that is, the space AF. Since the height [of point] B is as far from the height [of point] A as the height [of point] D is from the height [of point] C (as has been supposed), the body that falls from height A, if it hits a resistant placed in front of height B, would not produce a greater effect (because of the second common sentence) than that produced by the [body] that falls from height C over a similar resistant placed in front of height D. Therefore (because of the third supposition), the mentioned two bodies travel at the same velocity when they pass the first [body] at height B, [that is,] at point H, and the other [body] at height D, [that is,] at point K. Consequently (because of the second supposition), the mentioned two bodies travel in equal times, one [through] the space GH and the other [through] the space IK. Therefore, the mentioned two bodies begin their movements (one at instant G and one at instant I) with equal velocity. Which was to be shown first. Since the body that comes from height A produces a greater effect on a resistant placed at instant F (because of the third common sentence) than the effect produced by the [body] that comes from height C on a similar resistant placed at point E, (because of the first supposition) the mentioned body coming from height A, when it arrives at the end of its movement (that is, at the instant or point F), moves faster than the [body] that comes from height C, and when it arrives at the end of its movement, that is, at the instant or point E. Which was to be shown secondly. This second point [of the argument] can be demonstrated also by means of another method. Of the entire longer line or transit GF, we take (because of the third [proposition] of the first [book] of Euclid) the part GM which is equal to the transit or shorter line IE. Since equally heavy bodies, similar and equal to each other, all begin their natural motions with the same velocity (as demonstrated above), the body that starts at height A travels along the space GM as fast as the body that starts at height C along the space IE, that is, they travel in equal times. |

|

LIBRO PRIMO - 5v - cont. |

FIRST BOOK - 5v - cont. |

|

|

Et perche lo detto corpo: che ſe partiße dall’altezza A (per la precedente propoſitione) andaria piu ueloce per lo ſpacio MF che per lo ſpacio GM (per comuna ſcientia) andaria anchora piu ueloce per lo detto ſpacio MF che l’altro per lo ſpacio IE che il medemo ſecondo propoſito. Propoſitione III. Quanto piu un corpo egualmente graue ſe andara luntanando dal ſuo principio, ouer propinquando al ſuo fine, nel |

Since the mentioned body that starts from height A (because of the previous proposition) travels faster along the space MF than along the space GM, (because of the common knowledge) it also travels faster along the mentioned space MF than along the other space IE, which is the same as the second point [of the argument]. Third proposition. The more an equally heavy body moves away from its beginning in a violent motion, that is, the closer it gets to its end, |

|

LIBRO PRIMO - 6r |

FIRST BOOK - 6r |

|

|

moto uiolente, tanto piu andara pigro e tardo. ESſempi gratia, ſel fuſſe una poßanza mouente in ponto A che tirare uoleße, ouer doueße un corpo egualmente graue uiolentemente per aere, et che tutto il tiro che far poteße, ouer doueße la detta poßanza con eßo corpo fuße tutta la linea AB. Dico che quello tal corpo quanto piu il ſe andaße aluntanando dal ſuo principio (cioè da lo iſtante A) ouer approßimando al ſuo fine (cioè allo istante B) tanto piu ſe andaria alentando de uelocita, la qual coſa ſe dimoſtrara in queſto modo. Diuideremo tutta la detta linea, ouer tranſito AB in piu ſpacij, et ſiano BC, CD, DE, EF, FG, GH et HA. Hor perche il detto corpo (per la quarta comuna ſententia) faria maggior effetto in un reſiſtente eßendo quello in ponto C che non faria eßendo in ponto B dilche  (per la prima ſuppoſitione) lo detto corpo andaria piu ueloce per lo ponto C che per lo ponto B et ſimilmente per lo ſpacio D[C] che per lo ſpacio CB coſi per le medeme raggioni lo detto corpo andaria piu ueloce per lo ſpacio ED che per lo ſpacio DC et per lo ſpacio FE che per lo ſpacio ED et per lo ſpacio GF che per lo ſpacio FE et per lo ſpacio HG che per lo ſpacio GF et per lo ſpacio AH49 che per lo ſpacio HG et ſe piu auanti fuße il principio di tal moto uiolente, tanto piu nelli ſeguenti ſpacii andaria ueloce, che è il propoſito. Questo medemo ſe ueriſica in cadauno che ſia uiolentemente menato uerſo a un luoco da eßo odiato: che quanto piu ſe ua approßimando al detto luoco, tanto piu ſe ua atriſtando in la mente, et piu cerca de andar tardigando. Correlario Primo. Onde el ſe manifeſta qualmente un corpo egualmente graue in lo principio d’ogni moto uiolente, ua piu uelocißimo, et |

the slower it travels. For example, let the moving power that wants or has to throw an equally heavy body violently through the air be at point A, and let the entire shot that the mentioned power could or should make be the entire line AB. I say that the farther away this body travels from its beginning (that is, from the instant A) or the closer it gets to the end (that is, to the instant B), the slower its velocity is, and this is demonstrated in the following way. We divide the entire mentioned line, or transit, AB into several spaces and these are BC, CD, DE, EF, FG, GH and HA. Now, since the mentioned body (because of the fourth common sentence) produces a greater effect on a resistant at point C than at point B, it follows  (because of the first supposition) that the mentioned body travels faster through point C than through point B and likewise through the space D[C]50 than through the space CB. Therefore, and for the same reasons, the mentioned body travels faster through the space ED than through the space DC, and through the space FE than through the space ED, and through the space GF than through the space FE, and through the space HG than through the space GF, and through the space AH51 than through the space HG. The farther away the beginning of the violent motion is, then likewise the faster it would travel in the previous spaces, which is to be shown. This same [effect] happens to everyone who has to go to an odious place: the closer he gets to that mentioned place, the sadder he becomes and the more he tries to slow down his journey. First Corollary. Hence, it is manifest that an equally heavy body travels fastest at the beginning of its violent motion and |

|

LIBRO PRIMO - 6v |

FIRST BOOK - 6v |

|

|

in fin piu tardisſimo che in ogni altro luoco, et quanto piu hauera a paſſare per piu longo ſpacio tanto piu in lo principio di tal mouimento andara uelocisſimo. Correlario. II. Anchor è manifeſto qualmente un corpo egualmente graue di moto uiolente non puo paſſare per dui diuerſi iſtanti de egual uelocita. Propoſitione. IIII. Tutti li corpi egualmente graui ſimili et eguali giongendo al fine de lor motti uiolenti andaranno de egual uelocita, ma dal principio di tali mouimenti, quella che hauera a paſſare per piu longo ſpacio ſe partira piu ueloce. ESfempi gratia ſel fuße due poßanze mouente dißimile, et ineguale luna in ponto A e l’altra in ponto C che tirar doueſſen dui corpi egualmente graui ſimili et eguali uiolentemente per aere, et che tutto il tiro: che far doueſſeno le ditte due poſſanze con eßi corpi l’uno fuße la linea AB et

|

slower than in any other place at the end. The longer the space is to travel, the faster it is at the beginning of its movement. Second corollary. It is also manifest that an equally heavy body [that moves] with violent motion cannot travel through two different instants with the same velocity. Fourth proposition. All equally heavy bodies, similar and equal to each other, travel with the same velocity when they arrive at the end of their violent motions. But, at the beginning of such movements those [bodies] that travel along longer spaces start off faster. For example, let there be two different and unequal moving powers, one at point A and the other at point C, that have to throw two equally heavy bodies, similar and equal to each other, violently through the air, and let the entire shots that the mentioned two powers realize with the mentioned bodies be line AB the first and

|

|

LIBRO PRIMO - 7r |

FIRST BOOK - 7r |

|

|

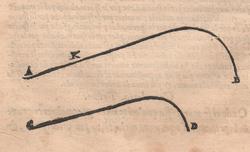

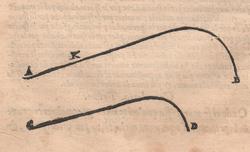

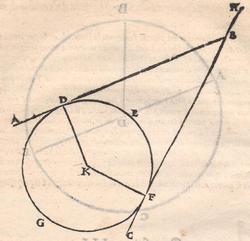

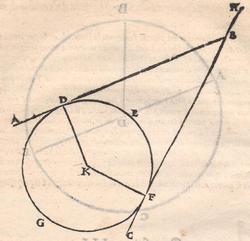

l’altro la linea CD. Dico che queſti dui corpi giongendo al fine di queſti dui lor mouimenti uiolenti, cioe l’uno allo iſtante, ouer ponto B et l’altro allo istante, ouer ponto D andariano de egual velocita. Ma dal principio di tali loro mouimenti cioe, l’uno da lo iſtante A et l’altro da lo iſtante C ſe partiriano de inegual uelocita, perche quello che doueria paßare per lo tranſito, ouer ſpacio AB (per eſſer piu longo di l’altro) ſe partira piu veloce da lo iſtante A che non fara l’altro da lo iſtante C la qual coſa ſe dimoſtrara in queſto modo. Perche ſe li detti dui corpi trouaßeno alcun reſiſtente in li dui iſtanti D et B li quali fußeno ſimili et eguali in reſistentia. fariano in eßi dui effetti (per la quinta ſuppoſitione) eguali onde (per la tertia ſuppoſitione) andariano de egual uelocita, che è il primo propoſito. A dimonstrar il ſecondo dal tranſito, ouer linea AB maggiore ne ſegaremo con la imaginatione la parte BK egual al tranſito, ouer linea CD, minore, et perche li detti dui corpi giongendo alli dui iſtanti D et B andariano de egual uelocita (come di ſopra è ſta dimoſtrato) haueriano tranſito de egual uelocita ſpacij egualmente distanti da li preditti dui lochi, ouer iſtanti B et D (per la ſeconda ſuppofitione) Adonca li detti dui corpi tranſiriano de egual uelocita l’uno per lo ſpacio KB partiale, et l’altra per lo ſpacio CD totale, cioè. Paßariano quegli in tempi eguali. Et perche quanto piu un corpo graue (nel moto uiolente) ſe andara aluntanando dal ſuo principio (per la terza propoſitione) tanto piu andara pigro e tardo. Adonque il corpo che ueniße da lo iſtante A andaria piu veloce per lo ſpacio AK che per alcun luoco del ſpacio KB partiale, ſeguita adonca (per comuna ſcientia) che il corpo che ueniße dallo istante A andaria piu ueloce per lo ſpacio AK che non andaria l’altro in alcun luoco di ſpacio CD totale. Il corpo adonque, che ueniſſe dal ponto, ouer istante A ſi parteria piu ueloce da eßo iſtante A, che non faria quello che ſe partiße da lo istante C da eßo iſtante C che è il ſecondo propoſito. Propoſitione. V. Niun corpo egualmente graue, puo andare per alcun ſpacio di tempo, ouer di loco, di moto naturale, e uiolente inſieme miſto. Esſempi gratia, ſel fuße una poßanza mouente in ponto A la qual doueße tirare un corpo egualmente graue uiolentemente per aere, et che tutto il tranſito: chi far doueße il detto corpo de quella ſpinto: fuße tutta la linea ABCDEF. |